|

CAIN WAS MORE THAN ABLE

JAMES M. CAIN ON THE OCCASION OF HIS BIRTHDAY, JULY 1, 2006 by J. Kingston Pierce

Thanks to Bill Crider for reminding me that today marks novelist/journalist James M. Cain’s 114th birthday. And I’m sure Cain would be celebrating, had he not already died an alcoholic at age 85, in 1977. Certainly best remembered as the author of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934), Double Indemnity (1936), and Mildred Pierce (1941), Cain was born in Maryland, aspired early to become a singer like his mother, worked in journalism with both H.L. Mencken and Walter Lippmann, and moved to Hollywood to write movie scripts but wound up penning cinematic novels, instead.  Most of Cain’s success as

an author came between the early Depression years of the ’30s and the

end of the Second World War. His hard-boiled yarns were usually

set in California (though one of his personal favorites, The Butterfly [1947], involves

incest and murder in the West Virginia coalfields). They often

revolved around men who fell in love with femme fatales, only to get

mixed up in criminal acts and eventually have their paramours betray

them. Raymond

Chandler, a Cain contemporary, was not overly fond of having his

work compared to that other novelist’s (despite the fact that he helped

Billy Wilder adapt Double Indemnity for the silver

screen). In a 1942 letter to the wife of his publisher, Alfred K.

Knopf, Chandler grumbled: Most of Cain’s success as

an author came between the early Depression years of the ’30s and the

end of the Second World War. His hard-boiled yarns were usually

set in California (though one of his personal favorites, The Butterfly [1947], involves

incest and murder in the West Virginia coalfields). They often

revolved around men who fell in love with femme fatales, only to get

mixed up in criminal acts and eventually have their paramours betray

them. Raymond

Chandler, a Cain contemporary, was not overly fond of having his

work compared to that other novelist’s (despite the fact that he helped

Billy Wilder adapt Double Indemnity for the silver

screen). In a 1942 letter to the wife of his publisher, Alfred K.

Knopf, Chandler grumbled: ... I hope the day will come when I won’t

have to ride around on [Dashiell]

Hammett and James Cain, like an organ grinder’s monkey.

Hammett is all right. I give him everything. There were a

lot of things he could not do, but what he did he

did superbly. But James Cain – faugh! Everything he

touches smells like a billygoat. He is every kind of writer I

detest, a faux naïf, a Proust in greasy overalls, a dirty little

boy with a piece of chalk and a board fence and nobody looking.

Such people are the offal of literature, not because they write about

dirty things, but because they do it in a dirty way. Nothing hard

and clean and cold and ventilated. A brothel with a smell of

cheap scent in the front parlor and a bucket of slops at the back

door. Do I, for God’s sake, sound like that?

Others, however, have been more generous to Cain. In his 1997 study of mystery fiction, Guilty Parties, Ian Ousby writes that Cain “is usually put first on the list of those American writers whose crime novels, without adopting the conventions of the hard-boiled school, breathe a distinctly hard-boiled atmosphere.” And The Oxford Companion to Crime & Mystery Writing (1999) opines that Compared with the voices and narration of

private-eye novelists with whom he was often compared, Dashiell Hammett

and Raymond Chandler, the diction of Cain’s narrators has the pure

simplicity of Horace

McCoy and of the more literary [Ernest] Hemingway; his plots were

more unified and tighter. Cain agreed with the observation that

his best work was “pure” – conceived and executed to produce an

experience for the reader, rather than to illustrate a moral or to lay

out any other thematic trappings. The purity and the staccato,

metallic style of The Postman Always Rings Twice so affected Albert Camus

that, in a revised version, he adapted it to the first-person narration

of The Stranger (1942).

Due to the fact that several of his early novels were turned into movies, Cain achieved a renown that probably wouldn’t have come his way otherwise. Yet his later turnout, primarily of tales with historical settings and paltry few of the trappings that would’ve earned them “hard-boiled” classification, were not nearly so well-received. Regardless, in 1970 James M. Cain was named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America. Reprinted

with permission from The

Rap Sheet, July 1, 2006.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Adapted from Crime Fiction IV, Allen J. Hubin.

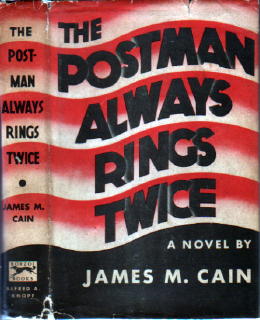

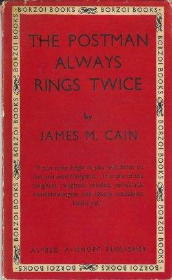

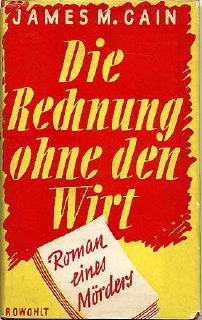

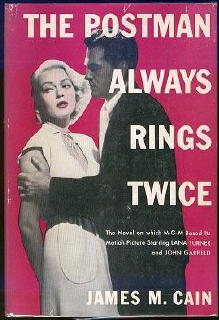

The Postman Always Rings Twice. Knopf, hc, 1934. Serenade. Knopf, hc, 1937. [Marginal crime content.] Mildred Pierce. Knopf, hc, 1941. Love’s Lovely Counterfeit. Knopf, hc, 1942. Career in C Major and Other Stories. Avon Modern Short Story Monthly 22, pbo, 1943. • “Career in C Major” Expanded from “Two Can Sing,” American Magazine, April 1938. • “Coal Black,” Liberty Magazine, April 3, 1937. • “The Girl in the Storm,” Liberty Magazine, January 6, 1940. Double Indemnity. Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #16, pbo, 1943. The Embezzler. Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #20, pbo, 1944. = Previously published as “Money and the Woman,” Liberty Magazine, 1938. Three of a Kind. Knopf, hc, 1944. • “Career in C Major.” Career in C Major and Other Stories, Avon, 1943. • Double Indemnity. Avon, 1943. • The Embezzler. Avon, 1944. Past All Dishonor. Knopf, hc, 1946. The Butterfly. Knopf, hc, 1947. The Moth. Knopf, hc, 1948. Sinful Woman. Avon Monthly Novel #1, pbo, 1948. Everybody Does It. Signet 759, pbo, 1949. Story collection. = Reprint of Career in C Major and Other Stories, with the addition of • The Embezzler. Avon, 1944. Jealous Woman. Avon Monthly Novel #17, pbo, 1950. The Root of His Evil. Avon 455, pbo, 1952. First appeared in The Avon All-American Fiction Reader, no editor stated, Avon 1002, 1951. = Reprinted as Shameless, Avon, pb, 1958. Galatea. Knopf, hc, 1953. Mignon. Dial, hc, 1962. The Magician’s Wife. Dial, hc, 1965. Rainbow’s End. Mason/Charter, hc, 1975. The Institute. Mason/Charter, hc, 1976. The Baby in the Icebox. Holt, hc, 1981. Story collection. • “The Baby in the Icebox,” The American Mercury, January 1933. • “The Birthday Party,” Ladies Home Journal, May 1936. • “Brush Fire,” Liberty Magazine, December 5, 1936 • “Coal Black,” Liberty Magazine, April 3, 1937. • “Dead Man,” The American Mercury, March 1936. • “The Girl in the Storm,” Liberty Magazine, January 6, 1940. • “Joy Ride to Glory.” • “Pastorale,” The American Mercury, March 1928. • “The Taking of Montfaucon,” The American Mercury, June 1929. = NOTE: The British edition (Robert Hale, hc, 1982) adds one story: • The Embezzler. Avon, 1944. Cloud Nine. Mysterious Press, hc, 1984. The Enchanted Isle. Mysterious Press, hc, 1985. COVER

GALLERY

James M. Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice. Knopf, 1934. This brutal little blue-collar love story was a shocking, sexy, “dirty” best seller and set the standard for tough, lean writing. It taught readers (and writers) that dialogue could propel a story by its own steam (and steaminess) with (as Cain himself put it) “a minimum of he-saids and she-replied-laughinglys.” From its famous first sentence (“They threw me off the hay truck at noon”) to its spellbinding final moments on death row, The Postman Always Rings Twice moves like a freight train, catching the reader up in a sleazy, unpleasant – and compelling – illicit love affair. Drifter Frank Chambers. finds himself in a roadside eatery called Twin Oaks Tavern (the first of many double images). Nick Papadakis, the friendly Greek who runs the place, has a wife who “really wasn’t any raving beauty, but she had a sulky look to her.” Soon Chambers is running the tavern’s gas station for the Greek; and by the end of chapter two, Frank and Cora have made a cuckold of him; by chapter four they are attempting Nick’s murder. And these are short chapters. Incredibly, the adulterers engage not just our interest but our sympathy, our collusion. Their lust (“I sunk my teeth into her lips so deep I could feel the blood spurt into my mouth”) is contagious, and redeemed by the extravagance of their passion (“I kissed her ... it was like being in church”). Yet Cain pulls no punches: Their intended murder victim, Nick, is not unsympathetic; Frank genuinely likes Nick, and after Frank and Cora succeed on the second try and kill him, cries genuine tears at his funeral. Frank and Cora – particularly Frank – are so out of control, so much smaller than the web of circumstance and human frailty in which they are caught up, that a strange sort of supportive interest develops for them. Cain feels for these small lovers who are doomed in so big a way. And so do we. When in the aftermath of Nick’s murder and the faked auto accident that follows, Cora and Frank indulge in a manic orgy of sadomasochism and passion at the scene of the crime, we are caught up in the moment with them. As Frank says: “Hell could have opened up for me then, and it wouldn’t have made any difference. I had to have her, if I hung for it.” Part of the enduring power of Postman is its evocation of the depression. Frank and Cora’s dream is the American one: They want a business of their own, a family of their own-simple goals that had been made so difficult in hard times. Their greed was small; their aspirations petty. Their love, and their crime, in James Cain’s tabloid opera, large. Reviewer: Max Allan

Collins.

James M. Cain, Serenade. Knopf, 1937.  Though lesser known than his more famous The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, Serenade is equally a masterpiece. Most of Cain’s best work is of novella length, but Serenade is an exception; a wider canvas is required for this more ambitious work with its subject matter that was daring even for Cain. The operatic undertone of Cain’s work comes to the fore here as an opera singer who loses his voice regains it by spending a night of lust and love with a Mexican whore in a deserted church during a thunderstorm. When John Howard Sharp returns to New York City and his singing career, the healing prostitute, Juana, is at his side; but they are soon faced with a threat from the past, the man whose homosexual liaison with Sharp had caused the singer’s traumatic loss of voice. In James M. Cain, there can only be one solution to such a situation: murder. But murder in Serenade isn’t born of greed and petty self-interest as it is in other Cain novels. The man and woman who share this sexual adventure are admirable and self-sacrificing. Their love is noble, and their tragedy is the deepest, most affecting in all of Cain. Cain wrote Serenade and his two other masterpieces in the 1930s; but his later, lesser (if interesting) works have tended to dilute his reputation. He is easily the peer of Hammett and Chandler, however, neither of whom wrote with Cain’s unabashed passion. Among his better later works are Past All Dishonor (1946) and The Butterfly (1947); they are, characteristically, in the first person. Mildred Pierce (1941) is the best of Cain’s third-person works. Several other completed novels are among Cain’s papers, and remain unpublished. Reviewer: Max Allan

Collins.

James M. Cain, Double Indemnity. Avon, 1943. James M. Cain, Double Indemnity. Avon, 1943.James M. Cain wrote of “the wish that comes true ... I think my stories have some quality of the opening of a forbidden box, and that it is this rather than violence, sex or any of the things usually cited by way of explanation that gives them the drive so often noted.” Double Indemnity employs this same technique, already displayed in The Postman Always Rings Twice, with dazzling ease. Cain, making a quick buck writing a magazine serial in 1936, did not realize it at the time, but he was at the top of his form. Employing skillful, scalpellike first-person narration, Cain tells his tale of love and murder from the point of view of a lover and murderer. Insurance man Walter Huff becomes embroiled in a plot to kill a beautiful woman’s husband. In addition to the sexual and financial incentives, Phyllis Nirdlinger manages to play upon Huff’s boredom and his pride – he knows the insurance game inside and out, and figures with his expertise he can beat it. The husband is murdered, according to Huff’s plan, without a hitch. But Huff is dogged by Keyes, a claims agent who also knows the insurance game inside and out. Huff begins to realize Phyllis is untrustworthy and just possibly insane, and falls in love with Lola, the daughter of the murdered man by a previous wife, who had very probably been yet another murder victim of Phyllis’s. Double Indemnity is a murder mystery turned inside out: We are forced inside the murderer’s skin, only to find it uncomfortably easy to identify with him, and then share his paranoia as the world crumbles piece by piece around him. Huff is a white-collar worker and he’s smart – smart enough to sense early on just how major a mistake he’s made. His sense of his own frailty and wrongdoing makes him a truly tragic protagonist, as does his sense of loss: “I knew I couldn’t have her and never could have her. I couldn’t kiss the girl whose father I killed.” Cain liked to explore the workings of businesses, and he never did it better than in Double Indemnity, through the characters of Huff and Keyes. But he also gave the pair an understated shared understanding of humanity (an aspect broadened in the widely respected Billy Wilder-directed, Raymond Chandler-scripted film version of 1944). In their final confrontation, Keyes says to Huff (renamed Neff in the film), “This is an awful thing you’ve done, Neff,” and Huff/Neff only says, “I know it.” And when Keyes says, “I kind of liked you, Neff,” Huff/Neff says, “I know. Same here.” Reviewer: Max Allan

Collins.

James M. Cain, Cloud Nine. Mysterious Press, 1984.  In the 1930s and 1940s,

James M. Cain was the most talked-about writer in America. His

novels of that period, like the detective novels of Dashiell Hammett, a

few years earlier, broke new ground in crime fiction. Until the

publication of The Postman Always

Rings Twice in 1934, sex was a topic handled with kid gloves

and almost always peripheral to the central story line; Cain made sex

the primary motivating force of his fiction, and presented it to his

readers frankly, at times steamily. (Some of the scenes in Postman are downright erotic even

by today’s standards.) In the 1930s and 1940s,

James M. Cain was the most talked-about writer in America. His

novels of that period, like the detective novels of Dashiell Hammett, a

few years earlier, broke new ground in crime fiction. Until the

publication of The Postman Always

Rings Twice in 1934, sex was a topic handled with kid gloves

and almost always peripheral to the central story line; Cain made sex

the primary motivating force of his fiction, and presented it to his

readers frankly, at times steamily. (Some of the scenes in Postman are downright erotic even

by today’s standards.)But Cain, of course, was much more than a purveyor of eroticism. His lean, hard-edged prose caused critics to label him a “hard-boiled” writer, but he is much more than that, too. His best works are masterful studies of average people caught up and often destroyed by passion (adultery, incest, hatred, greed, lust). They are also sharp, clear portraits of the times and places in which they were written, especially California in the depression era Thirties. Cain’s success began to wane in the Fifties and Sixties, however, partly because of a desire to write novels of a different sort from those that had brought him fame, and partly because of a clear erosion of his talents (a seminal fear of all writers) brought about by advancing age. Cloud Nine is one of those “different” novels, written in the late 1960s when Cain was seventy-five. It was rejected by his publisher at that time and shelved. Resurrected for publication in 1984, seven years after Cain’s death, it was puffed by its publisher as “an important addition in contemporary American literature” and by an advance reviewer as “a minor masterpeice and publishing event of some note.” It is none of those things. It is, simply and sadly, a flawed novel of mediocre quality – a pale shadow of his early triumphs. The novel’s basic premise is solid. A teenage girl, Sonya Lang, comes to Maryland real-estate agent Graham Kirby with the news that his nasty half brother, Burwell, has raped her and that she is pregnant as a result. Through a complicated set of circumstances, Graham agrees to marry Sonya, initially for charitable reasons; but he soon falls in love with her. He then discovers that Burwell may be a murderer as well as a rapist, and that another murder may be part of Burwell’s future plans. The conflict between Burwell and Graham forms the central tension here, with Sonya as one catalyst and a million dollars in prime real estate as another. All the elements are present for a classic Cain novel, ones that should combine to keep the reader on tenterhooks, “anxious to find out what happens,” as Cain biographer Roy Hoopes says in an Afterword, “but always dreading the ending because of the horror [he senses] would be waiting – ‘the wish that comes true’ that Cain said most of his novels were about.” But the elements simply don’t mesh. The bulk of the novel is taken up with the relationship (much of it sexual) between Graham and Sonya, to the exclusion of everything else; Burwell doesn’t even appear on stage until page 108, and other major plot points are introduced sketchily and/or not developed until the final fifty to sixty pages. Graham is a rather dull and unappealing narrator, not at all one of “those wonderful, seedy, lousy no-goods that you have always understood,” as one of Cain’s friends described the protagonists of Postman and Double Indemnity. And the prose is anything but lean and hard-edged. It reads as if Cain, late in life, discovered and became enamoured of commas and clauses, as witness the novel’s opening sentence: “I first met her, this girl that I married a few days later, and that the papers have crucified under the pretense of glorification, on a Friday morning in June, on the parking lot by the Patuxent Building, that my office is in.” Not everything about Cloud Nine is weak; there are some crisp passages of dialogue reminiscent of vintage Cain, the character of Sonya is well developed, and there is power in the climactic scenes (although none of the existential terror and tragedy of the early books). But on balance, and like the other suspense novels Cain wrote late in life – The Magician’s Wife (1965), Rainbow’s End (1975), The Institute (1976) – it is minor and disappointing. Reviewer: Bill

Pronzini.

The preceding four reviews by are reprinted by permission from 1001 Midnights: The Aficionado’s Guide to Mystery and Detective Fiction, Bill Pronzini and Marcia Muller, editors, Arbor House, 1986. Copyright © 1986 by Bill Pronzini and Marcia Muller. YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. Unless otherwise

specified, all material copyright © 2006 by

Steve

Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors.

|