CHARLIE CHAN, THE ENDURING DETECTIVE

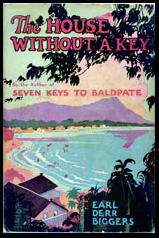

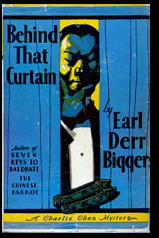

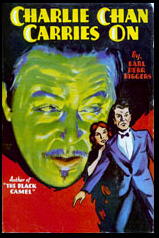

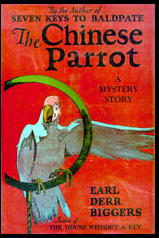

by Marv Lachman Except for Sherlock Holmes, Charlie Chan was once arguably the world’s most famous detective. Then, in the 1960’s both Asian-American and African-American groups protested the television showing of films about Chan. Strangely, the former group found Chan a negative stereotype. The latter group had more reason to complain. Beginning with Charlie Chan in Egypt (1935), blacks were often added to the casts for comic relief, and their portrayals were offensive. In that movie Stepin Fetchit played a character called “Snowshoes.” In the films made by Monogram Studios, Chan had a chauffeur named “Birmingham Brown,” played by Mantan Moreland, whose reaction to danger was chattering teeth and the line, “Feets get me out of here!” Release of video cassettes and showing Chan films on cable television around 1990 introduced a new generation to the Hawaiian sleuth. Then political correctness seemed to rear its head. Typical was Charlie Chan Is Dead, a 1993 anthology of contemporary Asian-American fiction, edited by Jessica Hagedorn, whose stated goal was to destroy what she considered stereotypes. It has been years since I’ve noticed a Chan movie in the TV listings. American Movie Classics, the cable channel that once showed the films, began showing commercials, which may account for its cautiousness. Those who have read the six books by Earl Derr Biggers about Charlie Chan still remember them, and, in view of the above controversy, it is worth reexamining the canon.  Like some other detectives (Albert Campion and Sir Henry Merrivale), Chan apparently became a series sleuth almost as an afterthought. Biggers was reported to have been surprised at Chan’s popularity. In his first book, The House Without a Key (1925), Chan doesn’t speak his first words until page 82 (of the first paperback edition), and they, despite his calling himself a student of English, are typically ungrammatical: “No knife are present in neighborhood of crime.” Biggers does not give him any of his famous aphorisms, and he doesn’t get to speak the book’s best line, about a chorus girl who is a “self-made widow.” In this book Biggers seemed especially interested in depicting Honolulu and its effect on members of a family of Boston Brahmins. Charlie continues to massacre English in The Chinese Parrot (1926), referring to something as “undubitable.” He demonstrates great stoicism in the face of racial slurs, while using his Chinese origins to pretend to be a cook, for purposes of detections. Charlie endures seasickness crossing the Pacific on his way to deliver pearls to a ranch in the California desert. When he lands, he says, “All time big Pacific Ocean suffer sharp pain down below, and toss about to prove it.” In this book we get our first taste of the Chan wisdom as it relates to life and detection. He incorporates a famous quotation when he says, “One wrong deed leads on to other wrong deeds. Like unending chain. Chinese have saying that applies: ‘He who rides on tiger can not dismount.’ “ He expresses some of his philosophy of detection: “Detective business consist of one unsignificant (sic) detail placed beside other of same. Then with sudden dazzle, light begins to dawn.” When Charlie describes patience as a “very nice virtue,” another character says Chan has “a bigger supply than any man I ever met.”  In Behind That Curtain (1928) Chan delays his return home, though his wife is expecting their eleventh child, due to a matter of honor. Scotland Yard Inspector Duff asked him to help with a San Francisco murder, one which has its origin in a past killing in London. Agreeing, Charlie says, “The facts must be upearthed (sic).” Championing patience again, he points out, “Patience always brightest plan in these matters. A cting as champion of that lovely virtue, I have fought many fierce battles. American always has the urge to leap too quick. How well it was said, ‘retire a step and you have the advantage.’” Charlie also cautions against “hoarsely barking up incorrect tree.” Chan’s typical modesty and self doubt also come to the fore. He says, “The fool questions others, the wise man questions himself... Even great detective steps off on wrong foot. My wrong foot often weary from too much use.” Charlie is back home (and promoted from sergeant to inspector) in The Black Camel (1929), investigating the Waikiki Beach murder of a Hollywood actress. In a paraphrase of dialogue found in many mystery movies, he says, “Let nothing be touched until I touch it.” There is also a scene reminiscent of many in the Chan films. Charlie has found a letter from the victim, which may disclose her killer. Before he can read it, the lights go out, he is struck on the head, and the letter is stolen. Charlie continues to mangle English – albeit delightfully – when he tells a suspect, “I could place you beneath arrest.” In this case he is assisted by Kashimo, a local policeman of Japanese origin, who annoys him greatly. Chan must put up with hearing someone refer to Chinese as “heathen.” The same person asks when Chan appears to investigate, “Why can’t they send a white man?” There are scenes of the Chan family at their home on Punchbowl Hill. To his favorite child, daughter Rose, who tells him the world is changing and becoming faster, he reluctantly agrees, replying, “Should I pause to think deeply I would be plenty lonesome man.” The title of this book is attributed to an old Eastern saying that “Death is the black camel that kneels unbidden at every gate.” Charlie uses some animal imagery himself when he says, “The man who is about to cross a stream should not revile the crocodile’s mother.”  Chan does not appear until more than halfway through Charlie Chan Carries On (1930). When Inspector Duff is wounded, Charlie takes his place on the last leg (Honolulu to San Francisco) of the around-the-world trip on which Duff has been trailing a killer since London. Kashimo is still bumbling along, and Charlie describes him as “useful as a mirror to a blind man.” Yet, Charlie seems to be warming up to this assistant who has the role (minus the “gee, Pop” dialogue) usually played by one of his sons in the movies. Kashimo even stows away on the ship, something Keye Luke, Victor Sen Yung, or Benson Fong might have done. Chan tells Kashimo, who shows a genius for searching cabins, “Do not belittle own attainments any longer. Stones are cast alone at fruitful trees, and one of these days you may find yourself in veritable shower of missiles.” Regarding his own weight, Charlie says, when offered food before dinner, “What I require most is a non-appetizer.” Throughout the series, Chan expresses a love of travel, and in the final book, Keeper of the Keys (1932), he is in California’s Sierras, achieving his ambition of seeing snow. He is recognized but deprecates his own fame, claiming, “He who stands on pinnacle has no place to step but off.” The case involves a much married opera singer about to marry again. Regarding infidelity, Chan says, “Ginger grown in one’s own garden is not so pungent.” He also says in this book: “We must collect at leisure what we may use in haste. The fool in a hurry drinks his tea with a fork.” Earl Derr Biggers died on April 4, 1933, shortly before the great popularity of the Chan B-pictures in Hollywood. He left behind only six novels about him and not a single short story or novelet. I’m at a loss to understand militant Asian-Americans’ objections to Charlie Chan. He is a devoted family man who is patient, wise, loyal, and has a sense of humor. The novels about him, reread recently for an article I did for a volume of the Dictionary of Literary Biography, will stand the test of time if read in 2055 better than many of those being published today. Unfortunately, other than the limited distribution of the editions from Wildside Press, I don’t believe any have been reprinted in at least twenty years. Note: This article originally appeared in CADS #16 (May 1991) and has been revised for its appearance online in Mystery*File.

A CHARLIE CHAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY - compiled by Steve Lewis

Earl Derr Biggers  The House Without a Key. The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1925. Grosset & Dunlap, hc, 1932? Triangle Books, hc, 1940. Pocket #50, 1940. Popular Library #132, 19–. Paperback Library 52-325, Oct 1964. Pyramid T-2004, May 1969. Bantam, 1974. Mysterious Press, 1986. Wildside Press, hc/trade pb, 2003. The Chinese Parrot. The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1926. Grosset & Dunlap, hc, 1930? Pocket #168, 1942. Avon #344, 1951. Paperback Library 52-228, July 1963. Pyramid T1970, 1969. Bantam N8447, 1974 Mysterious Press, 1987.  Behind That Curtain. The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1928. Grosset & Dunlap, hc, 1930? Pocket #191, Dec 1942. Paperback Library 52-296, June 1964. Pyramid T-1971, 1969. Bantam, 1974. Popular Library, 1987. Wildside Press, hc/trade pb, 2003. The Black Camel. The Bobbs-Merill Co., 1929. Grosset & Dunlap, hc, 1930? Pocket #133, 1941. Paperback Library 52-312 , Aug 1964. Pyramid T-1947, Jan 1969. Bantam, 1975. Mysterious Press, 1987. Wildside Press, hc/trade pb, 2003.  Charlie Chan Carries On.

The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1930. Charlie Chan Carries On.

The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1930.Grosset & Dunlap, hc, 1930? Pocket #207, 1943. Avon #350, 1951. Paperback Library 52-283, Apr 1964 [abridged]. Pyramid T-1946, 1969. Bantam Q6415, 1975. Mysterious Press, 1987. Wildside Press, hc/trade pb, 2003. Keeper of the Keys. The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1932. Grosset & Dunlap, hc, 1935? Triangle Books, hc, 1940. Dell #47, 1944. Paperback Library 52-208, Apr 1963. Pyramid T-2003, 1969. Bantam Q6418, 1975. Mysterious Press, 1988. Wildside Press, hc/trade pb, 2003. Robert Hart Davis [house name] “Walk Softly Stranger.” Short novel published in Charlie Chan Mystery Magazine, November 1973. “The Silent Corpse.” Short novel published in Charlie Chan Mystery Magazine, February 1974. Robert Hart Davis [Michael Collins] The Temple of the Golden Horde. Wildside Press, hc/trade pb, 2003. Short novel reprinted from Charlie Chan Mystery Magazine, May 1974. Robert Hart Davis [Bill Pronzini & Jeffrey M. Wallman] The Pawns of Death. Wildside Press, hc/trade pb, 2003. Short novel reprinted from Charlie Chan Mystery Magazine, August 1974. Dennis Lynds Charlie Chan Returns. Bantam N8868, pb, Nov 1974. Novelization of an unproduced(?) television screenplay. Michael Avallone Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen. Pinnacle 41-505, pb, Feb 1981. Novelization of the film of the same name. The British mystery fanzine CADS is published irregularly by Geoff Bradley, 9 Vicarage Hill, South Benfleet, Essex SS7 1PA, England. For a sample issue, send £5 (UK) or $10 (US/Canada, airmail). Please make checks payable to G. H. Bradley. _____________________________________ YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME.

Copyright © 1991, 2005 by

Marvin Lachman.

Return to

the Main Page.

|