|

FORGOTTEN WRITERS: GIL BREWER,

by Bill Pronzini

I don’t like the

Murder, She Wrote TV show. I don’t like the

Murder, She Wrote TV show. I don’t like it because it gives a false and distorted picture of what it’s like to be a mystery writer. Dear Jessica effortlessly produces a couple of novels that become instant bestsellers. Critics and readers adore them, every one. Film and play producers flock to her door, offering huge amounts of money. She attends fancy New York parties and everyone knows her name, everyone praises her work. Small towns, ditto. Foreign countries, ditto. Her agent is a prince; so are her U.S. and foreign publishers. She has no career setbacks, no private demons. She writes when she feels like it, which isn’t very often, and never has to worry about money. Her life is full of adventure, romance, excitement, joy. It is the kind of life even royalty envies. Well, bullshit. You want to know what the life of a working mystery writer is really like? Gil Brewer could tell you. He could tell you about the taste of success and fame that never quite becomes a meal; the shattered dreams and lost hopes, the loneliness, the rejections and failures and empty promises, the lies and deceit, the bitterness, the self-doubts, the dry spells and dried-up markets, the constant and painful grubbing for enough money to make ends meet. He could tell you about all of that, and much more. He would, too, if he were still alive. But he isn’t. Gil Brewer drank himself to death on the second day of January, in the Year of Our Lord nineteen hundred and eighty-three, at the age of sixty. . . . Last year [1981]

I nearly croaked; not through drinking, but because I had an infected

lung, emphysema, heart failure and pneumonia-all at the same

time. It was a rough go at the hospital. Then nearly a year

of sobriety and I figured I was ready for work, when things went to pot

again. . . . I’m ashamed of all the evil damned things I’ve done

when drinking. [But] I’m straight now, and must remain so,

because one more drink and Gil Brewer goes down the slot.

Sure, it’s a cliche. Look at all the writers who have destroyed themselves with alcohol. Poe, Stephen Crane, O. Henry, Jack London, Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy Parker, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, O’Hara. And Hammett. And Chandler. And hundreds more. So does it really matter that a minor mystery writer named Gil Brewer also drank himself to death? Damned right it does. It matters because he was a gentle, sensitive, vulnerable man who felt too deeply and cared too much. It matters because he produced some of the most compelling noir softcover originals of the 1950s. It matters because he understood and loved fine writing and hungered to create it himself, to just once write something of depth and beauty and meaning. It matters because of the writer he might have been with a little luck, encouragement, and the proper guidance, for in him there was a small untapped core of greatness. It matters because if it doesn’t, then nothing does. . . . For all my seemingly sometimes

rattlebrained manner, I am actually deathly sincere and serious about

my writing. . . Am only happy – my only real happiness – at the

machine.

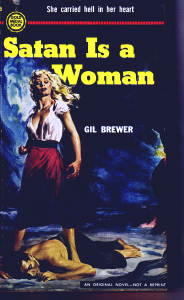

Gil Brewer was born in relative poverty in Canandaigua, New York, in November of 1922. He dropped out of school to work, but retained a thirst for knowledge and a love of books; he was an omnivorous reader. At the outbreak of World War II he joined the army and served in France and Belgium, seeing action and receiving wounds that entitled him to a VA disability pension. After the war, he worked at a variety of jobs – warehouseman, cannery worker, bookseller, gas-station attendant – while pursuing a lifelong desire to write fiction. His early efforts were not crime stories but mainstream and “literary” exercises. He sent some of these to Joseph T. Shaw, the former editor of Black Mask, who had become a successful literary agent in the forties. Shaw liked what he saw and encouraged Brewer to keep writing, though with a more commercial slant to his work. I began as a “serious”

writer, and came close, but married and had to have money so switched

to pulp. I was with Joe Shaw at that time. I sold shorts to

Detective Tales,

etc. Shaw had my entire career planned. I tried writing a

suspense book to see if I could do it, and wrote one singles-paced in

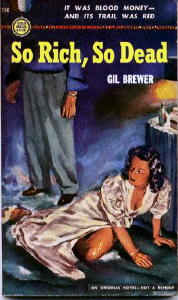

five days. Then I wrote Satan Is a Woman and Gold Medal bought it and asked for

more – Dick Carroll and Bill Lengel – and Joe said to me, “You’ve

already got another one [finished]. The five-day book, So

Rich, So Dead.” So GM published

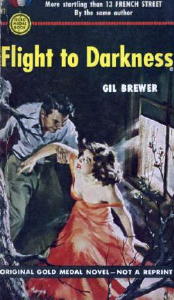

that. Then I wrote 13 French Street and was off to the races.

Fawcett was the first and

best of the softcover

publishers to specialize in original, male-oriented mysteries,

Westerns, historicals, and “modern” novels. Their Gold Medal line

was in its infancy (the first GM titles appeared in late 1949) when

they bought Brewer’s first two novels in 1950; but GM’s success was

already guaranteed. They had assembled, and would continue to

assemble, some of the best popular and category writers of the period

by paying royalty advances based on the number of copies printed,

rather than on the number of copies sold; thus writers received

handsome sums up front, up to three and four times as much as hardcover

publishers were paying. Into the GM stable came such established

names as W. R. Burnett, Cornell Woolrich, Sax Rohmer, MacKinlay Kantor,

Wade Miller, and Octavus Roy Cohen; such top pulpeteers as John D.

MacDonald, Bruno Fischer, Day Keene, David Goodis, Harry Whittington,

Edward S. Aarons, and Dan Cushman; and such talented newcomers as

Charles Williams, Richard S. Prather, Stephen Marlowe, and Gil Brewer. Fawcett was the first and

best of the softcover

publishers to specialize in original, male-oriented mysteries,

Westerns, historicals, and “modern” novels. Their Gold Medal line

was in its infancy (the first GM titles appeared in late 1949) when

they bought Brewer’s first two novels in 1950; but GM’s success was

already guaranteed. They had assembled, and would continue to

assemble, some of the best popular and category writers of the period

by paying royalty advances based on the number of copies printed,

rather than on the number of copies sold; thus writers received

handsome sums up front, up to three and four times as much as hardcover

publishers were paying. Into the GM stable came such established

names as W. R. Burnett, Cornell Woolrich, Sax Rohmer, MacKinlay Kantor,

Wade Miller, and Octavus Roy Cohen; such top pulpeteers as John D.

MacDonald, Bruno Fischer, Day Keene, David Goodis, Harry Whittington,

Edward S. Aarons, and Dan Cushman; and such talented newcomers as

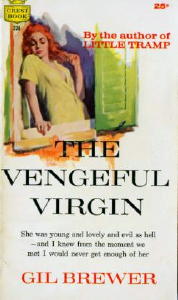

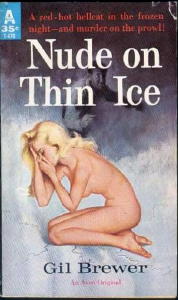

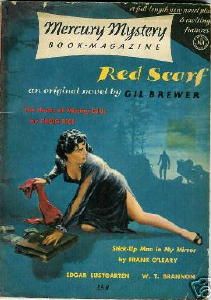

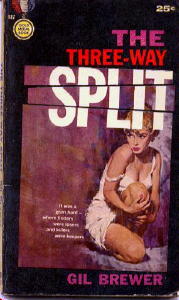

Charles Williams, Richard S. Prather, Stephen Marlowe, and Gil Brewer.What the Fawcett brain trust and the Fawcett writers succeeded in doing was adapting the tried-and-true pulp fiction formula of the thirties and forties to postwar American society, with all its changes in life-style and morality and its newfound sophistication. Instead of a bulky magazine full of short stories, they provided brand-new, easy-to-read novels in the handy pocket format. Instead of gaudy, juvenile shoot-’em-up cover art, they utilized the “peekaboo sex” approach to catching the reader’s eye: women depicted either nude (as seen from the side or rear) or with a great deal of cleavage and/or leg showing, in a variety of provocative poses. Instead of printing a hundred thousand copies of a small number of titles, they printed hundreds of thousands of copies of many titles so as to reach every possible outlet and buyer. They were selling pulp fiction, yes, but it was a different, upscale kind of pulp. On the one hand, the novels published by Fawcett – and by the best of their competitors, Dell, Avon, and Popular Library – were short (generally around fifty thousand words), rapidly paced, with emphasis on action. On the other hand, they were well-written, well-plotted, peopled by sharply delineated and believable characters, spiced with sex, often imbued with psychological insight, and set in vividly drawn, often exotic locales. . . the stuff of any good commercial novel, then or now. Thanks to writers such as Gil Brewer, the best of the Gold Medal novels are the apotheosis of pulp fiction – rough-hewn, minor works of art, perfectly suited to and representative of their era. What has been labeled as pulp since the early sixties is not the genuine article; it is an offshoot of pulp, or a mutation of pulp, reflective of the “new world” that has been created by the technological and other sweeping changes of the past twenty-five years. The last piece of true-pulp-as-art was published circa 1965. Readers responded to the Gold Medal formula with enthusiasm and in huge numbers. It was common in GM’s first few years for individual titles to sell up to five hundred thousand copies, and not all that unusual for one to surpass the one million mark. Brewer’s 13 French Street, published in 1951, was one of those early million-copy bestsellers, going into eight separate printings and many overprintings. Yet 13 French Street is not his best novel. A deadly-triangle tale of two old friends, one of whom has fallen mysteriously ill, and the sick one’s evil wife, it has a thin and rather predictable plot, and too much of the narrative takes place in the house at the title address. Nevertheless, it has all of the qualities that give Brewer’s work its individuality and power. The prose is lean, Hemingwayesque (Hemingway’s influence is apparent throughout the Brewer canon), and yet rich with raw emotion genuinely portrayed and felt. It makes effective use of one of his obsessive themes, that of a weak, foolish, and/or disillusioned man corrupted and either destroyed or nearly destroyed by a wicked, designing woman. And it has echoes – especially in the use of Saint-Saens’s Danse Macabre as a leitmotif – of the haunting surreality and existentialism that infuses his strongest work. With the success of 13 French Street, Brewer was indeed “off to the races.” Over the next nine years, Fawcett’s editors bought and published a dozen more of his novels, nine under the Gold Medal imprint and three under their Crest imprint, generally reserved for hardcover reprints. All but one were contemporary suspense novels; the lone exception is Brewer’s only Western novel, Some Must Die (1954), an excellent variation on the theme of good people and bad thrown together and entrapped by the elements. (The cover art and blurbs for Some Must Die were carefully crafted to give the impression that it was modern suspense rather than Western suspense. Brewer’s readers weren’t fooled, though; Some Must Die sold the fewest copies of his early books.)  Despite some lurid titles

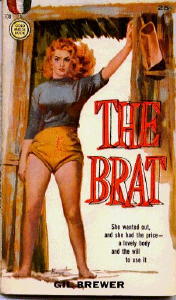

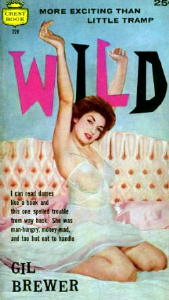

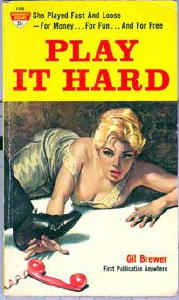

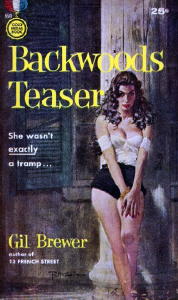

– Hell’s Our Destination, –And the Girl Screamed, Little Tramp, The Brat, The Vengeful Virgin – Brewer’s

fifties GM and Crest novels are neither sleazy nor sensationalized;

they are the same sort of realistic crime-adventure stories John D.

MacDonald and Charles Williams were producing for GM, and of uniformly

above-average quality. Most are set in the cities, small towns,

waterways, swamps, and backwaters of Florida, Brewer’s adopted

home. (The exceptions are Some

Must Die and 77 Rue Paradis

(1954), which has a well-depicted Marseilles setting.) The

protagonists are ex-soldiers, ex-cops, drifters, convicts, blue-collar

workers, charterboat captains, unorthodox private detectives, even a

sculptor. The plots range from searches for stolen gold and

sunken treasure to savage indictments of the effects of lust, greed,

and murder to chilling psychological studies of disturbed personalities. Despite some lurid titles

– Hell’s Our Destination, –And the Girl Screamed, Little Tramp, The Brat, The Vengeful Virgin – Brewer’s

fifties GM and Crest novels are neither sleazy nor sensationalized;

they are the same sort of realistic crime-adventure stories John D.

MacDonald and Charles Williams were producing for GM, and of uniformly

above-average quality. Most are set in the cities, small towns,

waterways, swamps, and backwaters of Florida, Brewer’s adopted

home. (The exceptions are Some

Must Die and 77 Rue Paradis

(1954), which has a well-depicted Marseilles setting.) The

protagonists are ex-soldiers, ex-cops, drifters, convicts, blue-collar

workers, charterboat captains, unorthodox private detectives, even a

sculptor. The plots range from searches for stolen gold and

sunken treasure to savage indictments of the effects of lust, greed,

and murder to chilling psychological studies of disturbed personalities.Probably the best of his Fawcett originals is A Killer Is Loose (1954), truly harrowing portrait of a psychopath that comes close to rivaling the nightmare visions of Jim Thompson. It tells the story of Ralph Angers, a deranged surgeon and Korean War veteran obsessed with building a hospital, and his devastating effect on the lives of several citizens of a small Florida town. One of the citizens is the narrator, Steve Logan, a down-on-his-luck ex-cop whose wife is about to have a baby and who makes the mistake of saving Angers’s life, thus becoming his “pal.” As Logan says on page one, by way of prologue, “There was nothing simple about Angers, except maybe the Godlike way he had of doing things.” Brewer maintains a pervading sense of terror and an acute level of tension throughout. Although the novel is flawed by a slow beginning and a couple of improbabilities, as well as an ending that is a little too abrupt, its strengths far outnumber its weaknesses. Two aspects in particular stand out: one is the curious and frighteningly symbiotic relationship that develops between Logan and Angers; the other is a five-page scene in which Angers, with Logan looking on helplessly, forces a scared little girl to play the piano for him – a scene Woolrich or Thompson might have written and Hitchcock should have filmed. A Killer Is Loose – in fact, all of Brewer’s early novels – was written at white heat and almost entirely firstdraft. This accounts for their strengths, in particular the headlong immediacy of the narratives, and for their various weaknesses. It seemed to be the only way Brewer could write: fast, fast, with black coffee and cigarettes and liquor to help him get through the long sleepless periods, and pills to help him come down afterward. I batted out those Gold Medal

books for so very long, never taking more than two weeks on one, and

once wrote one in three days – in fact more than one – and often in

five or six days – and they all sold. I possibly thought it would

continue forever, poor fool that I am, but with never any encouragement

toward better stuff, except on one occasion I recall that didn’t work.

***

The fifties was

Brewer’s decade; satisfied with his

work or not, he was a commercial success. In addition to his

books for Fawcett, he sold suspense novels to Avon, Ace, Monarch,

Bouregy. He continued to write short stories, too, under his own

name and such pseudonyms as Eric Fitzgerald and Bailey Morgan, and

placed them with most of the digest-sized mystery magazines of the time

– Manhunt, The Saint, Pursuit, Hunted, Accused – as well as with numerous

men’s magazines. His new agent (Joe Shaw died in 1952) sold film rights

to four of his GM books: 13 French

Street, A Killer Is Loose,

Hell’s Our Destination

(poorly filmed as LURE OF THE SWAMPS),

and The Brat. Almost

everything he wrote found a publisher. And almost every one of

his novels, if not every one of his short stories, had more than a

little merit. The fifties was

Brewer’s decade; satisfied with his

work or not, he was a commercial success. In addition to his

books for Fawcett, he sold suspense novels to Avon, Ace, Monarch,

Bouregy. He continued to write short stories, too, under his own

name and such pseudonyms as Eric Fitzgerald and Bailey Morgan, and

placed them with most of the digest-sized mystery magazines of the time

– Manhunt, The Saint, Pursuit, Hunted, Accused – as well as with numerous

men’s magazines. His new agent (Joe Shaw died in 1952) sold film rights

to four of his GM books: 13 French

Street, A Killer Is Loose,

Hell’s Our Destination

(poorly filmed as LURE OF THE SWAMPS),

and The Brat. Almost

everything he wrote found a publisher. And almost every one of

his novels, if not every one of his short stories, had more than a

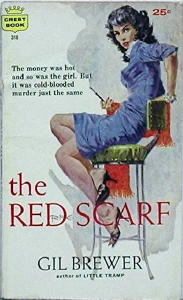

little merit.Outstanding among his non-Fawcett books of the fifties, and two of his best overall, are The Red Scarf (Mystery House, 1958) and Nude on Thin Ice (Avon, 1960). The former title has an interesting history. It was inexplicably rejected by Fawcett and other paperback houses, and eventually sold to the lending-library publisher, Thomas Bouregy, for a meager $300 advance; it was Brewer’s second and last book to appear under Bouregy’s Mystery House imprint – the first was The Angry Dream (1957) – and his second and last U.S. hardcover appearance. After publication of The Red Scarf, Fawcett’s editors had a sudden change of heart and decided the book was worthwhile after all: they bought reprint rights (presumably for much less money than they would have had to pay Brewer for an original) and republished it as a Crest title in 1959. The Red Scarf is narrated by motel owner Ray Nichols. Hitchhiking home in northern Florida after a futile trip up north to raise capital for his floundering auto court, Nichols is given a ride by a bickering and drunken couple named Vivian Rise and Noel Teece. An accident, the result of Teece’s drinking, leaves Teece bloody and unconscious; Nichols and Rise are unhurt. At the woman’s urging, he leaves the scene with her and the money – and it is only later, back home with his wife, that he discovers Teece is a courier for a gambling syndicate and that the money belongs to the syndicate, not to either Teece or Rise. While he struggles with his conscience, several factions begin vying for the loot, including a Mob enforcer, the police, and Teece. There are some neat plot turns, the various components mesh smoothly, the characterization is flawless, and the prose is Brewer’s sharpest and most controlled. Anthony Boucher said in the New York Times that the book is the “all-around best Gil Brewer. . . a full-packed story.”  Nude on Thin Ice is a much darker and more surreal novel. Set primarily in the Sandia Mountains of New Mexico, it has a deadly triangle plot reminiscent of 13 French Street, though much different in execution. The three main characters are drifter Kenneth McCall, the lonely widow of one of his old friends, and a strange and exotic nymphet who enjoys posing naked on ice for men and their cameras. Half a million dollars in cash and an implacable lawyer named Montgomery also figure prominently, as does explosive violence both expected and unexpected. What makes the novel memorable is its brooding narrative, its mounting sense of doom, and an ending that is both chilling and perfectly conceived. The narrator, McCall, is one of Brewer’s most striking creations – weak and immoral on the one hand, so sadly tragic on the other that the reader cannot help but empathize with his fate. At least some of the nightmare, existential quality of Nude on Thin Ice can be attributed to Brewer’s increasing dependency on alcohol and sleeping pills. By 1960 he was living a private nightmare of his own. His success had begun to wane. Overexposure, a slowly changing market, the darkening nature of his fiction. . . these and intangibles had led to a steady decline in sales of his Gold Medal and Crest originals after the high-water mark of 13 French Street, to the point where Fawcett decided to drop him from its list. In his world-by-the-tail decade, he published twenty-three mostly first-rate novels under his own name, fifteen of those with Fawcett; between 1961 and 1967, he published a total of seven mostly mediocre novels – one last failure with Gold Medal (The Hungry One, 1966) and the other six with second-line paperback houses (Monarch, Berkley, Lancer, Banner). In the late fifties he and his wife, Verlaine, had moved out west. It was not a good move for Brewer. In Florida he had had a coterie of writer friends, among them Harry Whittington, Frank Smith (Jonathan Craig), and Talmage Powell. In Colorado and New Mexico, he missed their counsel and support when he began selling less and drinking more. There was also the fact that he was beginning to be strapped for money; he had lived high off the hog in his salad days, saving and/or investing little. Financial worries combined with the professional frustrations to lead him into protracted binges. More than once he entered a clinic to dry out, only to backslide again after his release. A major crash of some kind was inevitable; it happened in 1964. . . . I was drowning in

alcohol and drugs, [and then came] the bleary morning I awakened to a

tall, cold glass of vodka on the bedside table, left the house for

breakfast at a friend’s, and was warned loudly by an echoing voice on a

comer to “Turn back-go home,” which I ignored, only to, an hour later,

total a creamy Porsche and pick up 8 broken ribs, 28 fractures, tom

lung, etc., in the process. Then the wild, rather ribald,

hallucinatory hospitalization. . . peopled with Bozo the Clown,

Rhine-maidens, and other happenings that could only be described as

other-worldly or science-fictional; a mad doctor, a hospital nightclub,

etc. – the beginning of a transfer to hell during which, for a time, at

least, I turned out novels and stories, all the while in the very

depths of the pit.

He wrote half a dozen sex books under house names for downscale publishers. He wrote stories by the dozens, mostly for the lesser men’s magazines, only now and then placing a crime short with Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and the lower-paying digests. In the late sixties he wrote three novelizations of episodes of the then popular Robert Wagner TV series It Takes a Thief; published by Ace in 1969 and 1970, these were the last novels to appear under his own name. He wrote four Gothics as by Elaine Evans for Lancer and Popular Library. On an arrangement with Marvin Albert, he wrote two of the Soldato Mafia series published by Lancer under Albert’s Al Conroy pseudonym. He ghosted an Ellery Queen paperback mystery, The Campus Murders (Lancer, 1969); a Hal Ellson suspense novel, Blood on the Ivy (Pyramid, 1971) and five of the novels about the Israeli-Arab war purportedly written by Israeli soldier Harry Arvay. (He had a chance to take over ghosting of the Executioner series as well – what would have been a major source of income – but while his one effort pleased the publisher, it did not please Don Pendleton.) He hated every minute of this type of work, but he always – or almost always – did the best possible job with the material he had to work with. And at this stage of his fading career, he always – or almost always – delivered as promised and on time. . . . I keep hoping for

a [subsidiary] sale of some kind; something that might complement the

exemplary qualities of my work, ahem. [I’m] up one minute when possibilities of-movie

rights, or perhaps reprint rights on some lost seed throng my konk, and

down the next on Realization Flight 110, knowing that publishers simply

are lethargic, fickle, disoriented-and-one-track-oriented ...

Ah me. (Ah Me’s a Chinese philosopher with rancid breath who appears as a ghost at my shoulder – he’s from back in 3,000 BC – and forever bids me to go with the tide.) Or maybe better yet, woe is me. At times I do feel exergued. Rats, how I ramble. The notorious Griffin, me, once again, with that dazzling old blue hope, ready to whoop it up at the party, hypostatic, ineffable, even, you might say, but unable to partake of the inducive viands and nectar because of insuforial earth-worms called editors who are, after all, so fucking hidebound, shade-eyed and ponderous it makes me scream – in agony. In agony. Brewer managed to keep turning out short stories for Hustler, Chic, and similar magazines, as well as occasional novel ideas and proposals ... until the drinking once more slid out of any semblance of control. It not only affected his ability to write, it put him in dangerously poor health. He knew something had to be done, and he did it: he voluntarily joined AA. The program seemed to work for him, at least for a while. Eventually he was able to return to work on a regular schedule. When his agent wrote to tell him that the Canadian publisher Harlequin was looking for mysteries for its new Raven House line, the prospect of once again writing suspense fiction under his own name energized him; he promised to come up with an idea, fifty pages, and an outline. But he soon realized that he was not as attuned to crime fiction as he had once been. Tried valiantly to read

some contemporary suspense stuff, so I’d be up on how character was

handled. Tisk. It coddled my fidgeting brain.

Awful. Sparse and futile. . . So many writers are taking old

writers’ plots these days, like Raymond Chandler’s yarns, and rewriting

them. I just don’t go that way. Perhaps I’m stupid, but it

seems a sloppy damned way to make a buck.

And so he couldn’t seem to get his head into a book for Harlequin. He had what he felt was a good idea: a novel about the world of bisexuals and homosexuals called The Skeleton. The problem lay in putting the right words down on paper. Suppose you’ve been

wondering why I seem to have been so bloody lax about this Harlequin

project. The fact is I had a small relapse – no drinking, or

anything like that, just an inability to read one of the [Raven

House] books so I could get the

formula down pat. Was trying too hard, obviously. Hope

you’ll excuse any screwy letters dashed off during this hectic

interim. Seem to be getting back in place now, for the most part,

though my concentration isn’t perfect – but believe I’ll be at work

soon. I have these spells, as you know. . .

More time passed, and he still couldn’t write The Skeleton proposal. At length he shelved it in favor of a new novel concept, one that excited him tremendously because it was the sort of serious work he longed to do, and intensely personal and therapeutic as well: an imaginative-autobiographical novel about his alcohol-and-drug-abusing days in the early sixties. The title was to be Anarcosis. It’ll be written in sequences

of dream-reality, with the dream as reality and the reality as dream. .

. It peregrinates all over the U.S. and ends with that bedeviled

incarceration in a mental institution back in ’64 . . . a big sweep of

both subjective and objective shocks, strung with startling characters

who, phantomlike, pre-destined and Martian in appeal, connect with me

in one way or another – traveling hospitals on the highways of America,

a besieged trip to Mexico on sleeping pills and bourbon, various alky

wards including the one I call Insanity Ranch in New Mexico, a pack of

dogs chasing me at four o’clock in the morning in Albuquerque when I

planned to walk to California, and many crazy, firefly incidents that

send me screaming through the blinding tunnel of day-mare into my own

private Gehenna to survive, or so it seems, anyway. There are

dialogues with internationally celebrated dead such as Jack London,

Arnold Bennett, Lytton Stratchy [sic], and numerous others, political figures

and men and women in the arts; psychic adventures with tortuous

conflict, and, at the end, a promise of another book to come called Man

on Tape. . .

He had telephone discussions about the project with his agent, who was impressed enough at its potential to write to the Fine Arts Council of Florida in an (ultimately futile) effort to get Brewer a grant that would ease his financial burden. As excited as Brewer was about the project, however, he had trouble writing it. This led to another, albeit brief and different setback. . . . I was on a valium

binge. There’s been no drinking, but that pill thing was evil-all

done for good now. No more of that – ever! No more of

anything except life, work, recovery. Recovery from a lifetime of

knowing I knew as much as the gods, was, in fact, perhaps, one of them

– and all I want to do is write. Write with the knowledge now

that I know nothing. Helpless, hopeless exactitudes.

He managed, finally, to get thirty-five pages of Anarcosis written to his satisfaction and sent them to his agent in February of 1978. The regretful evaluation was that it was “just short of unreadable. .. uncontrolled, hallucinatory dynamism,” and it was the agent’s suggestion that Brewer rethink it and rewrite it in a more coherent and commercial fashion. The agent also suggested that because of Brewer’s financial straits, it would be best if he devoted his immediate energies to short stories for such well-paying markets as Hustler, or the long-overdue Harlequin proposal. At first Brewer balked at this advice. . . . I am going to devote all my

energies to Anarcosis. I cannot, so help me, face another pulp

project – at least, not now. It turns my stomach. It has

given me diarrhea; the very thought of it, the attempts to turn a plot

again, again, again! I cannot do it.

It was not long, though, before he relented. He had no choice; as always, he was living hand to mouth-mostly on a VA disability pension and a Social Security pension. He forced himself to complete the fifty pages-and-synopsis of The Skeleton. Then, encouraged by his agent’s favorable response, he wrote a portion-and-outline for a second mystery, Jackdaw. After that was delivered, he agreed to take on a massive rewrite-and-ghost-job – an original manuscript bought by a minor paperback house of which there were two different, unacceptable versions, one of 426 pages and the other of over 1,100 pages. He was to rework the mish-mosh pair into an intelligible, publishable book. The project was a disaster from the beginning. He had long, violent telephonic clashes with the book’s editor that eventually, after months of labor and psychic drain, forced him off the job with only nominal payment. As if this bitter pill wasn’t enough to swallow, Harlequin rejected The Skeleton portion, after holding it for several months, because although they felt it read entertainingly and “would surely make a good mystery novel,” the bisexual/homosexual content was deemed unacceptable. Jackdaw was not bought either, for more obscure reasons. These, combined with continuing frustrations with Anarcosis, were the final straws. By mid-1979 Brewer was again drowning in booze. In 1980 one of his writer friends wrote sadly to another, “ . . . Gil has drunk the tops off all the vodka bottles and is writing very little, alas.” Brewer’s redescent into the depths of alcohol and despair continued into 1981, when he nearly died of several different ailments. Then, with Verlaine’s help, he managed to lift himself out of the pit for the final time. He rejoined AA; he tried once more to put his life back together. I no longer drink and attend

AA meetings regularly. Last eve a head cheese in the organization

suggested I’d be a good speaker. I told him he’d have to wait

till I have some front teeth replaced-three have fallen out, God help me

[and] I can’t afford to go to a

dentist.

In late April of 1982 he wrote an abject, rambling, five-page letter to his agent. I’m hanging by a thread and practically

living on noodles and rice with the way things are. The bloody

Social Security disability pension and the VA disability pension could

give out any time, and I’d be on the streets. I just skin by each

month as it is, living like a hermit. Maybe grass, good green

grass, I mean, would be a treat...

All I know is, I must write. I love

to write. I can sit at the mill again, and I can write the stuff.

. . I’ve got to make money, but in return I’ll deliver better

goods than ever. . . I have so many terrific books in me!

And I no longer drink, nor do I take any drug that would disrupt the

scene. I’m sober and ready for work.

But it was too late. Over the previous several years there had been too much conflict, too many failures and missed assignments, and during the dark, alcoholic years of 1979 through 1981 there had been to many incoherent, angry, pleading letters, too many drunken phone calls. The agent said that his agency and Brewer were “moving in different directions” and wished him well; their thirty-year professional marriage was finished.  In August Brewer wrote Mike Avallone, asking Mike to help him find new representation. . . . Could you write a brief note to

your agent and see if he’d be willing to take me on as a client?

I must still have some rep: I’ve sold over 50 novels. . . about four

hundred short stories and novelettes. . . have been published in 26

countries. . . I have some new, fresh material at hand, and would

dearly love an assignment . . . All I need and want now is an

agent, a good one, and a word processor. But at the moment I feel

terribly lost and in limbo.

Nothing positive came of this, despite Avallone’s efforts. And so, inevitably, Brewer plummeted into the pit for the final time. In December, shortly before Christmas, he placed one last telephone call to his former agent. He was so drunkenly incoherent that the agent had no idea of what he was saying or why he called. Two weeks later, on the morning of the second day of the new year, Verlaine entered his apartment and found him dead. That is not quite the end of the Gil Brewer story, however. The gods can be perverse sometimes – damned perverse. This is one bitter instance. In the years since January 2, 1983, a French film company paid a five-figure advance for film rights to A Killer Is Loose and produced it in 1987. Two other early GM novels, 13 French Street and The Red Scarf, were bought for reissue by Zomba Books in England; those two and a number of others were also reissued in France. Black Lizard has expressed interest in reprinting several Brewer titles here. And a number of his short stories were purchased for anthologies edited by the writer of these words. Gil Brewer is dead, but his career, by God, is not; new life has been breathed into it, and it is still on life support at the time of this writing. . . . I’m encouraged by how I feel toward

really good stuff. It turns me on, as it always has – but I’ve

always denied myself the pleasure of [such] work; forever tied up with one project

after the other, facing the stricture of money needed. . .

Everything in my plans hinges on money as a support; I’m tortured out

of my skull when the gelt is low. . .

And the drinking... I always imagined it a necessity for my work. I am a terrible fool. AFTERWORD  The italicized passages

in this piece were taken

verbatim from letters written in 1977, 1978, and 1982 by Brewer to a

number of individuals, primarily his agent and Mike Avallone.

None of the letters were addressed to me personally; I had no

correspondence with Gil Brewer, did not know him at all. The italicized passages

in this piece were taken

verbatim from letters written in 1977, 1978, and 1982 by Brewer to a

number of individuals, primarily his agent and Mike Avallone.

None of the letters were addressed to me personally; I had no

correspondence with Gil Brewer, did not know him at all.In retrospect I find this strange, discomfiting, because on numerous occasions from the late sixties to the early eighties I intended to write Brewer a letter; to tell him that I grew up reading his work, admired it, was in fact influenced by it in certain small ways. I did write similar letters to such other writers as Evan Hunter, Robert Martin, Jay Flynn, Talmage Powell, but never one to Brewer. In the mid-seventies I went so far as to track down his address and type it on an envelope, yet no farther than that. I don’t know why. I wish I had written to him, established a correspondence, gotten to know him a little. I might have been able to help him in some small way: bought some of his old stories for anthologies while he was still alive, maybe, or given him an assignment to write an original... something. It would have made absolutely no difference in the long run, of course. Just the same, I can’t help feeling a bit guilty for my silence. Maybe I’m a fool, too, in my own way. Maybe we all are, us real-life working mystery writers. . . ***

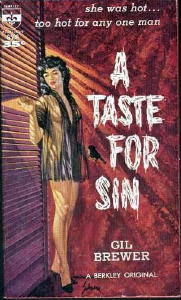

Originally appeared in Mystery Scene Magazine. Reprinted from The Big Book of Noir (Carroll & Graf, 1998). Copyright © 1989 by Bill Pronzini. In the early 1950s, Gil Brewer lived in Florida and played poker once a week with a group of his friends who also wrote paperback originals, including Day Keene and Harry Whittington. Day Keene’s son, the writer Al James, told me that Gil once confided to him that he had taught Keene and Whittington everything they knew about writing. On another night, Whittington explained to Al that HE had taught both Brewer and Keene how to write. And sure enough, Al’s Dad would often tell his son how he taught Whittington and Brewer everything they knew about storytelling. Maybe there’s a little truth in all three claims. US editions only (with two exceptions) As by Gil Brewer: * = listed in Hubin, Crime Fiction IV, as having only marginal crime content. Satan Is a Woman. Gold Medal #169, pbo, June 1951. Gold Medal #169, pb, 2nd pr. Gold Medal #169, pb. 3rd pr., October 1951.  So Rich, So Dead. Gold Medal #196, pbo, 1951. 13 French Street. Gold Medal #211, pbo, 1951. Gold Medal #211, pb, 2nd pr. Gold Medal #418, pb, 3rd pr., 1954. Gold Medal #858, pb, 5th pr., February 1959. Gold Medal #k1326, pb, 6th pr., 1963. Gold Medal #d1801, pb, 1967. Flight to Darkness. Gold Medal #277, pbo, December 1952. Hell’s Our Destination. Gold Medal #345, pbo, October 1953. A Killer Is Loose. Gold Medal #380, pbo, March 1954. Some Must Die. Gold Medal #409, pbo, June 1954. 77 Rue Paradis. Gold Medal #448, pbo, December 1954. The Squeeze. Ace Double D-123, pbo, 1955. Paired with Love Me to Death, by Frank Diamond. * And the Girl Screamed. Crest #147, pbo, 1956. The Angry Dream. Mystery House, hc, 1957.  Reprinted as The Girl from Hateville. Zenith #ZB7, pb, 1959. The Brat. Gold Medal #708, pbo, 1957. Gold Medal #708, 2nd pr., Gold Medal #s1258, pb, 3rd pr., 1962. Little Tramp. Crest #173, pbo, 1957. Crest #173, pb, 2nd pr., 1958. Crest #418, pb, 3rd pr., 1960. The Bitch. Avon #830, pbo, 1958. The Red Scarf. Mystery House, hc, 1958. – appeared earlier in Mercury Mystery Book-Magazine, Vol. 1 #3, Nov 1955. Crest #310, pb, July 1959. Wild. Crest #229, pbo, July 1958. Gold Medal #k1466, pb, 1964. The Vengeful Virgin. Crest #238, pbo, September 1958. Wild to Possess. Monarch #107, pbo, January 1959. Monarch #364, pb, 2nd pr., 1963. Angel. Avon #866, pbo, 1959.  Sugar. Avon T335, pbo, 1959. The Girl from Hateville. Zenith ZB-7, pb, November 1959. (Paperback edition of The Angry Dream, hc, 1957). Nude on Thin Ice. Avon T470, pbo, 1960. Backwoods Teaser. Gold Medal #950, pbo, 1960. The Three-Way Split. Gold Medal #987, pbo, April 1960. Play it Hard. Monarch #168, pbo, 1960. Monarch #444, pb, 2nd pr., 1964. Appointment in Hell. Monarch #187, pbo, March 1961. A Taste for Sin. Berkley G509, pbo, 1961. Memory of Passion. Lancer 70-008, pbo, 1962. The Hungry One. Gold Medal #d1647, pbo, 1966. The Tease. Banner #B50-102, pbo, February 1967.  Sin for Me. Banner #B50-108, pbo, June 1967. It Takes a Thief #1: The Devil in Davos. Ace #37598, pbo, 1969. It Takes a Thief #2: Mediterranean Caper. Ace #37599, pbo 1969. It Takes a Thief#3: Appointment in Cairo. Ace #37600, pbo, 1970. In collaboration with Day Keene: Love Me and Die. Phantom #504, pbo, 1951. (Credited to Keene only.) Harlequin (Canada) #167, pb, 1952. Paperback Library 51-156, pb, 1962. Manor 95287, pb, 1973. As by Ellery Queen: The Campus Murders. Lancer 74-527, pbo, 1969. (The Troubleshooter #1.) Note: Other Troubleshooter titles are by other ghostwriters.  As by Hal Ellson: Blood on the Ivy. Pyramid T2257, pbo, 1970. As by Elaine Evans: (Gothic romances.) Shadowland. Lancer 74-705, pbo, 1970. Magnum 74-705, pb, no date. A Dark & Deadly Love. Lancer 75-403, pbo, 1972. Magnum 75-403, pb, no date. Black Autumn. Lancer 78-752, pbo, 1973. Magnum 78-752, pb, no date. Wintershade. Popular Library 00530, pbo, 1974. As by Al Conroy: Al Conroy was a pen name of Marvin H. Albert. There are five books in the “Soldato” series. Albert wrote #1, 2 and 5, while #3 & 4 are ghostwritten by Gil Brewer.  Strangle Hold! Lancer 75-433, pbo, 1973. Soldato #3. Murder Mission! Lancer 75-459, pbo, 1973. Soldato #4. As by Harry Arvay: Series character: Max Roth in all. The Moscow Intercept. Bantam Q6345, pbo, 1975. FOOTNOTE. Eleven Bullets for Mohammed. Bantam Q7626, pbo, 1975. Operation Kuwait. Bantam Q7759, pbo, 1975. The Piraeus Plot. Bantam Q2048, pbo, 1975. Togo Commando. Corgi 10157, UK pbo, 1976. FOOTNOTE: In all, there are an even dozen titles, all spy thrillers of one form or another, that have been credited to Harry Arvay, who was a real person, not a house name. He was an Israeli soldier with plenty of enthusiasm but no talent for writing. It is known that Gil Brewer took on the task of converting five of Arvay’s long manuscripts into workable novels. For some time now, the question has been which ones? Here is what the thinking has been: Four of the Arvay books were published by Bantam in the US. Early on it was confirmed that the other three Bantam editions above were done by Brewer, along with Togo Commando, which was one of the Arvay books published only in England. It therefore seemed logical that The Moscow Intercept, the fourth book from Bantam, was also written by Brewer. But when George Tuttle did a prelimary comparison of a few passages from Moscow with the original manuscript held at the American Heritage Center, his conclusion at the time (as stated in a previous version of this bibliography) was that they did not match. The Moscow

Intercept is

the fifth Gil Brewer Avray book. The University of Wyoming sent

me the first three pages of the manuscript of The 12th Bullet, and though that

manuscript is not the book as published, it is clear from the “Authors

Note” that it could not be any other Avray book.

Case closed. The Moscow Intercept is now included as part of the Gil Brewer bibliography. As by Mark Bailey: (Adult.) Mouth Magic. Barclay House #7230, pbo, 1972. (6 printings under various titles and bylines) As by Luke Morgann: (Adult.) More than a Handful! Beeline #785T, pbo, 1972. Ladies in Heat. Beeline #795T, pbo, 1972. Gamecock. Beeline #837T, pbo, 1972. X-rated rewrite of Angel, as by Gil Brewer. Tongue Tricks! Beeline #876T, pbo, 1972. Gil Brewer wrote many short stories for mystery digests and magazines under his own name and as Eric Fitzgerald and Bailey Morgan. ***

Sources and inspiration: Hubin’s Crime Fiction, Bill Pronzini, Ed Gorman, Mimi Rhodes (who told me about Love Me and Die), David Wilson (who corroborated Mimi’s story), Victor Berch, Al James and George Tuttle. An earlier version of this checklist

appeared in 1995 and was updated

in 2006. Copyright © 1995, 2006 by Lynn Munroe.

_____________________ Also

recommended is a website set

up by George Tuttle as part of a project to create an even more

comprehensive bibliography of Gil Brewer, including his short fiction

work.

YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. |