THE WORKS OF G. T. FLEMING-ROBERTS by Monte Herridge  A brief introduction to

this checklist of the works

of the pulp author G. T. Fleming-Roberts (born George Thomas Roberts,

1910-1968). There are over 300

stories in this bibliography, and it is still probably not

complete. There are doubtless more stories awaiting

discovery. The list below excludes many details about the

stories, which I have recorded in a database containing page numbers,

total story pages, and so on. The list below generally

includes first appearances only and with a few exceptions, does not

include most

reprints. Fleming-Roberts wrote many stories about

magician-detectives; most of these are in three series: Diamondstone,

The Ghost/Green Ghost, and Jeffery Wren. A brief introduction to

this checklist of the works

of the pulp author G. T. Fleming-Roberts (born George Thomas Roberts,

1910-1968). There are over 300

stories in this bibliography, and it is still probably not

complete. There are doubtless more stories awaiting

discovery. The list below excludes many details about the

stories, which I have recorded in a database containing page numbers,

total story pages, and so on. The list below generally

includes first appearances only and with a few exceptions, does not

include most

reprints. Fleming-Roberts wrote many stories about

magician-detectives; most of these are in three series: Diamondstone,

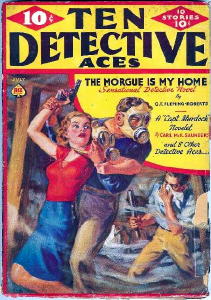

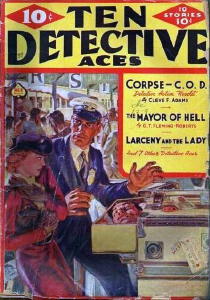

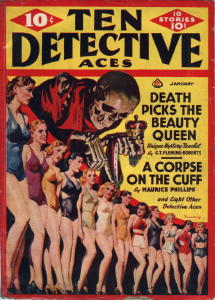

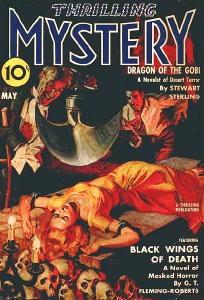

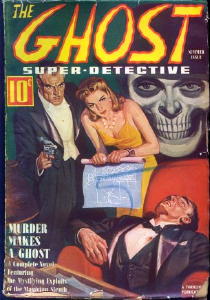

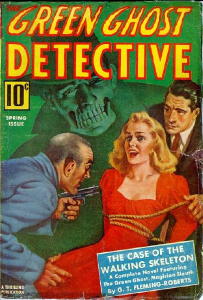

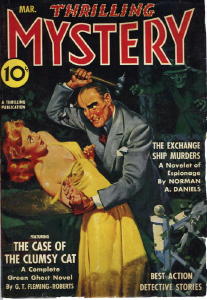

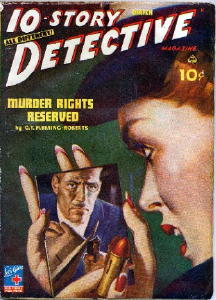

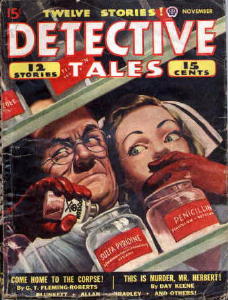

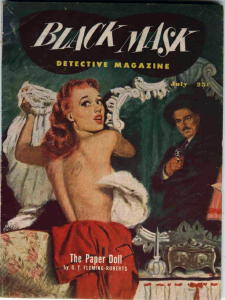

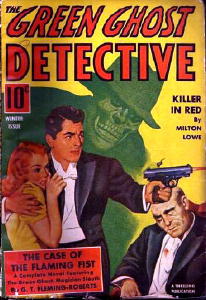

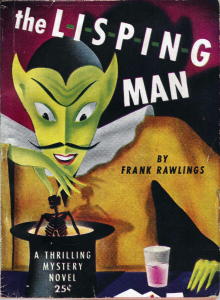

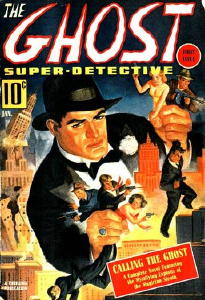

The Ghost/Green Ghost, and Jeffery Wren.Fleming-Roberts’ primary field of writing was mystery and detective fiction, along with the related fields of weird menace and the hero pulps. G. T. Fleming-Roberts was one of the workhorses of the pulp era, from his first story publication in 1933 to his last fiction appearance in Manhunt in 1955, a story entitled “Welcome Home.” There is a 1956 story in the first issue of Crime and Justice Detective Story Magazine that will probably throw off some readers. The title is “The Dead Man Said No”, and it appears to be a new story. However, it is a retitled reprint of “The Corpse Said No”, which originally appeared in the January 1950 issue of New Detective Magazine. Fleming-Roberts was a lifelong Indiana native. He did not have very many stories published in 1945-46 primarily because of his military service in that period. See Albert Tonik’s interview with Fleming-Roberts’ widow in Mike Chomko’s Purple Prose #17, July 2003, an issue which also included a short biography of the author. A piece by Fleming-Roberts in Writer’s Digest “The Turn From the Trite,” is an article on how to write pulp stories. It helps in understanding his approach to writing. The list also includes one unpublished story from 1941: “Suicide Squad,” and a few stories not known until recently because they were published under pseudonyms. The real author is now known for these stories because when the stories were reprinted in Canadian pulps the real name was used rather than the pseudonym. One story published this way is “Morgue Meat,” which was probably originally published in the February 1939 issue of Double-Action Gang under the house name of Undercover Dix. The real names of the authors are not always used in the Canadian edition, but they are on occasion. There is no telling how many other stories by various writers can be assigned to their correct names by close examination of the Canadian pulp editions. Other Fleming-Roberts stories appeared under various house names: “Trinidad Pay-Off” as by Ray P. Shotwell in the September 1943 issue of Fighting Aces, and one of the Masked Detective stories: “The Poison Puzzle”, as by C. K. M. Scanlon. The Ace line of pulps reprinted at least two of his stories under the house names Ralph Powers and Rexton Archer. Fleming-Roberts also revised his Ghost novel, “Calling the Ghost,” for paperback publication as The Lisping Man, which was published under the pseudonym Frank Rawlings. I wrote a short piece about this for Tom Johnson’s special edition of Echoes, entitled “Chance without a Ghost,” because the novel was revised to feature magician George Chance and leave out his Ghost alter ego. The story “Married to Murder,” which appeared in Argosy in 1945, was reprinted in the collection Best Detective Stories of the Year, edited by David C. Cooke, and published in 1946 by E. P. Dutton & Co. Many other of Fleming-Roberts’ stories have been reprinted recently in various formats, and some are available on the web at www.pulpgen.com.

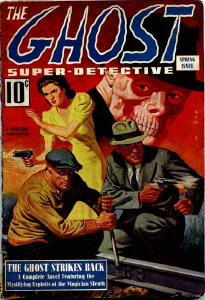

Footnotes: (1) All of the Ghost/Green Ghost stories have been collected in The Magical Mysteries of The Green Ghost, George Thomas Roberts as G. T. Fleming-Roberts (Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, two volumes, 2005). All you need to know about the character is in this book, which includes commentaries by noted pulp experts James T. Roberts, Garyn Roberts and Robert Weinberg. (2) According to one online source, this story was originally scheduled to appear in the Spring 1944 issue of Thrilling Mystery, but it never did. It was later rewritten to eliminate The Green Ghost from the story line, and the name of the character, George Chance, was changed to George Hazard. It is included in the Battered Silicon collection above. (3) Pat Oberron was Fleming-Roberts’ only series character who was a “normal” private detective. For more information on Oberron and the other eccentric tenants in Hillary House, the seedy building where his office is, read my article on him in the Fall/Winter 2006 issue of Blood 'n' Thunder magazine.  Probably the two best

known series of stories that G. T. Fleming-Roberts (1910-1968) wrote

for the pulps were his Secret Agent X novels he did for that magazine

and the Ghost/Green Ghost novels and novelettes he wrote for several

others. All of the stories belonging to each series are

well-known, yet one story in The Ghost series is rarely mentioned as

being one of them. This is the story The Lisping Man, printed in

hardcover by Gateway in 1942 and in paperback by Hercules Publishing in

1944. (One the back cover of the paperback it states that the

book is “An Atlas Mystery.”) The author’s name on the book is

Frank Rawlings, though in reality it was Fleming-Roberts who wrote it. Probably the two best

known series of stories that G. T. Fleming-Roberts (1910-1968) wrote

for the pulps were his Secret Agent X novels he did for that magazine

and the Ghost/Green Ghost novels and novelettes he wrote for several

others. All of the stories belonging to each series are

well-known, yet one story in The Ghost series is rarely mentioned as

being one of them. This is the story The Lisping Man, printed in

hardcover by Gateway in 1942 and in paperback by Hercules Publishing in

1944. (One the back cover of the paperback it states that the

book is “An Atlas Mystery.”) The author’s name on the book is

Frank Rawlings, though in reality it was Fleming-Roberts who wrote it.Upon examination of The Lisping Man, is it is easy to determine that it is a revised version of the first Ghost story in the pulps, “Calling the Ghost.” It is more than a slight revision, however; it has been changed considerably. Rather than detail all of the differences between the two stories, this short article will hit the highlights about the major differences and points. One comment first, however, before continuing. When I wrote the original version of this article, my observations were based on the paperback edition. The problem with this is that the paperback is an abridged edition of the hardcover novel. Without using a copy of hardcover edition as a basis for making comparisons, I have decided to remove from the earlier version some of the comments made on the structure of individual sentences and paragraphs. Alterations in the concept of the story, however, and in the characters themselves, are the differences which I feel able to point out. In the revised story, for example, George Chance is still in the story as the lead, but all references to the Ghost alter ego were removed. The character of Commissioner Standish was replaced by Inspector Ames, as another example. Ames is not as friendly toward Chance as Standish is, and the lack of a friend in the story changes its feel and Chance’s motivations. Medical Examiner Robert Demarest is in both versions of the story. However, in “Calling the Ghost” he is described as a friend, and in The Lisping Man this implication is removed, leaving doubt as to his actual relationship with George Chance. All scenes in the Ghost’s rectory hideout were removed. Any scenes involving the Ghost were rewritten to show George Chance involved instead and were simplified greatly. However, even with these alterations, it is as much a part of the Ghost series as the story “The Phantom Bridegroom,” in which the Ghost was turned into George Hazard. Fleming-Roberts wrote the original story, and was the one who also revised it for publication as a novel. He was not satisfied with the results of his revised story, so he used the Rawlings name for publication. Another major alteration in The Lisping Man is the change in the point of view of the story. The new version presents the story in the third person. The original pulp version presented the story in first person, from the point of view of George Chance, The Ghost. The third person narrative was used to some extent in the third and fourth stories in the series, and then was changed completely to the usual third person in the fifth story. Even the author in the earliest stories in the series was shown as “George Chance,” and it was changed to Fleming-Roberts in later stories only when the point of view was changed. Other differences in The Lisping Man begin immediately on the first page, which shows George Chance and Merry White newly married and arriving at his apartment. Anyone familiar with the pulp series knows that this event never happened in any of the stories. The first two pages are new material detailing this, as well as at many other times throughout the story. Below is an example of an addition is where the author changes a conversation between Chance and his assistant Joe Harper to one between Chance and his new bride, Merry White. When Chance learns of the death of Leonard Van Sickle after a flurry of phone calls and visitors on their wedding night, he actually wants to investigate the mystery, but he does not want to let Merry know. In the pulp version, he had no such concern, but went right ahead and made up as The Ghost to start investigating the crime.  “We’ll go to a hotel,” he said.

“Ames can’t do this to me.”

He was thoughtful, plucking at his chin as though it were a beard. He muttered, “Why would he do that?” “That’s what I want to know,” Merry padded around the bedroom barefooted, looking for her slippers. I still think my idea to spend our wedding night in Grand Central Station was just peachy compared with this!” “Why would he hide his false teeth?” She found her slippers, straightened slowly without putting them on, stared at her husband. “What are you talking about?” “Oh,” he said, startled, and grinned at her. “Oh, I was talking about Leonard Van Sickle.” “Darlin’,” she pleaded, “you’re not going to let Inspector Ames drag you into another murder case, are you?” He shook his head. “Of course not. You get dressed as fast as you can. We’ll go the Exeter House.” She gave him a sidelong glance. “And why the Exeter? “The – er –” He looked at her sharply. “The cuisine,” he said glibly. “It’s superb, you see?” As it happens, the Exeter House is just around the corner from the hotel in which Van Sickle met his death, and Merry has every reason to be suspicious. Most of Chapter Two was deleted. In the pulp story, this gave the background of The Ghost and his relationship to Commissioner Standish. With the new character of Inspector Ames in the story, no detailed description of their relationship was seen as necessary, although it is obvious in the story that Ames and George Chance knew each other. In the revised story, it was noted instead that “Chance had turned to crime detection as a hobby.” (Page 19.) This hobby was doubtless how Ames came to know him. Another significant change in The Lisping Man is the deletion of one of the Ghost’s agents: Tiny Tim Terry. Another assistant, Glenn Saunders, has an increased role in this story. He is Chance’s assistant in the George Chance Magic Shop, which is located off Broadway on Forty-Second Street. In “Calling the Ghost,” Saunders worked in Chance’s secret workshop in the basement of his house. The erasure of The Ghost from the story greatly affects it; the most significant effect is at the end of the story where the resolution scene was completely rewritten. Little of this part survives from the original story. In the original version, most of the suspects appear in the finale. In the revision, this is not the case. One character named Tanko was removed from the finale, being mentioned in the revision as having been shot by police off scene. In the original story, The Ghost uses his magic tricks on the suspects in order to complete the solution of the case. In the revision, Chance does the usual revelation of the crime before the suspects. The Lisping Man was probably aimed at a more adult audience than the pulp version. This can be seen by the marriage relationship of George Chance and Merry White, and also by another fact: When Chance was hiding out in the rooftop restaurant early in the story, he ordered beer in original story(and did not drink it), and hard liquor (rye, which he did drink) in the revised story. In the final summing up, it seems that “Calling the Ghost,” a fairly interesting hero story with a mysterious hero who performs magic to mystify criminals and solve crimes, has been revised into a rather ordinary mystery that is not as good as many of Fleming-Roberts’ mystery novelettes published in the pulps. In the original story, The Ghost is in command of events when he investigates the mystery; in the revised story, George Chance is at the mercy of events and trying to keep out of trouble. No wonder G. T. Fleming-Roberts did not want his name on the novel version of The Lisping Man. COMMENT: The earlier version of this article originally appeared in Tom Johnson’s special Echoes Revisited, 2002. G. T. Fleming-Roberts (1910-1968) seemed to like writing about magicians for the pulps. He not only wrote the Thrilling Group’s magician hero pulp stories about “The Ghost/Green Ghost” (published from 1940-1944) and the Diamondstone stories in Popular Detective from 1937-1939, but also wrote a series of seven stories about Jeffery Wren for Popular Publications’ Dime Detective. These were published in that title between 1944 and 1946 and vary from 18 to 28 pages in length. A number of the stories were favored by having the cover art for that month show a scene from the story. These seven tales appear to be all that were printed in the series.

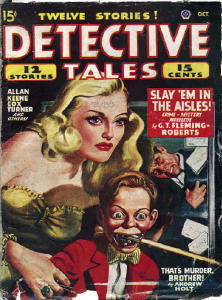

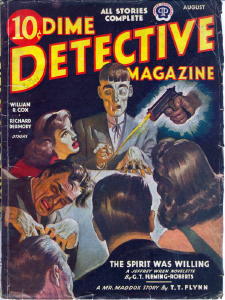

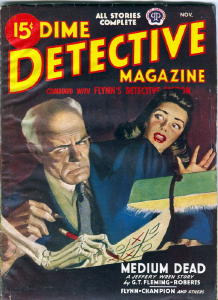

Why the series ended is not known, but Fleming-Roberts, like many other Americans, was in the military from the summer of 1945 to January 1946. So he probably did not have time to write any stories during that period of his life. The stories published in 1945 were in all likelihood written before he went into the military, and the 1946 story may have been written after his discharge. It is also possible that the series just ran out of steam and the editors of Dime Detective did not want any more Wren stories. Fleming-Roberts made certain that this series character was different than many other pulp detectives by giving him distinctive characteristics. Jeffery Wren runs a novelty and magic shop in the Brill Building on West Ohio Street in Indianapolis, Indiana. FOOTNOTE 1. The magic part of the shop is up a flight of stairs found at the back of the novelty shop. Here there is a door that has written on it “Wren’s Magic.” Through this door is a reception room with Wren’s old vaudeville photographs covering its walls and furnished with chairs of chrome and leather. From the reception room, double glass doors lead into the magic shop itself, which is filled with everything from practically invisible gimmicks to stage size professional illusions. Fleming-Roberts’ use of Wren’s vaudeville past is perfectly in line with the series’ time frame. Vaudeville was very popular earlier this century, until competition from movies and radio came along. The Great Depression finished it off. Many of history’s popular radio performers came from vaudeville. Fred Allen, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, Fanny Brice, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Eddie Cantor, George Jessel, Will Rogers, Ed Wynn, and many others all emerged from the vaudeville stage. Practically everyone at the time of the Wren stories’ publication was very familiar with vaudeville. There is little doubt Fleming-Roberts, when young, went to see vaudeville performers, including magicians. For those readers not familiar with vaudeville, it was a way of life for thousands of performers from around the time of the Civil War to the Great Depression. Thousands of performers with every imaginable type of act appeared in regional and national circuits, performing in theaters before a live audience. There were stand-up comedians, acrobatic acts, dancers, singers, magicians, and many other kinds of acts. “In lavish ‘palaces’ and modest opera houses, located in towns and cities knit together by railroad-defined circuits that spanned the nation, vaudeville served a vast public.” FOOTNOTE 2. It was family entertainment; its cleanliness strictly observed. Many vaudevillians appeared in small regional theaters and were considered “small timers.” The more successful acts ran in good theaters and on national circuits such as the B. F. Keith circuit that Jeffery Wren worked in. Thus Fleming-Roberts’ fictional character was one of the more successful type of vaudevillians. FOOTNOTE 3.  In Wren’s magic shop, his store assistant is Horace, a “lean, bloodless-looking clerk,” who mans the novelty part of the shop and sits behind the joke counter. He talks in a sloppy, off-hand manner, chews on a cigar he never lights, and has the attitude that the customer is always wrong. On occasion, Horace is drafted by Wren for various detective jobs such as following people. Horace seems to be more interested in women than anything else. Wren’s “sidekick snoop,” as the editors of Dime Detective described her, is Zoe Osbourn, a policewoman “assigned to snaring fortune tellers and fake mediums.” Zoe Osbourn is a widow in her late forties with “vividly hennaed hair” who dresses in loud clothes, and her heavy build is somewhat muscular. She has a husky, harsh voice with an emphatic delivery and uses blunt language which sometimes has a humorous turn. Some of her outbursts when surprised are “Fry me for a banana!” and “Horse liniment!” Her late husband was a police sergeant, and she keeps a picture of him in his uniform on the mantel of her white bungalow. She seems to be similar to the better-known Bertha Cool, Erle Stanley Gardner’s female detective who first appeared in book form in 1939. FOOTNOTE 4. Another regular in the series is the homicide detective, Sergeant Thomas “Tom” Hogan. He was added to the series in the third story and can be found in the rest of the series, a total of five appearances. He is mentioned as having known Wren for a long time. Hogan always seems to be running into the magician in the course of his murder investigations and considers Wren to be a nuisance. At one especially stressful point in the investigation entitled “Scare a Man to Death” (1/45), Hogan says, “I sometimes wish some people would go back into vaudeville, not mentioning any names.” However, Hogan always finds that in the end, Wren comes up with the murderer that he himself cannot find or an alternate to the person he has wrongfully accused. Jeffery Wren is not the usual brawny, violent, gun-toting crime investigator that often appeared in detective pulp stories. He is a sophisticated, middle-aged man of medium height with a heavy, squarish body. He walks with a bouncing stride. He is able to take care of himself in violent situations and has a well-developed sense of humor. Wren is portrayed as being very well-dressed; he wears a Homburg, rather than the usual fedora that so many other pulp detectives wore. He also wears a black fleece overcoat during the winter and a white linen suit in the summer. His appearance is described by the author as reminiscent of the Hollywood character actor Edward Arnold (1890-1956), best remembered today for his roles in three Frank Capra films – YOU CAN’T TAKE IT WITH YOU (1938), MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON (1939), and MEET JOHN DOE (1941). Arnold also appeared as a detective in a number of movies, including Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe in 1936’s MEET NERO WOLFE (Columbia Pictures). He also played Captain Duncan Maclain, a blind detective, in two excellent, underrated movies – EYES IN THE NIGHT (1942) and THE HIDDEN EYE (1945), both produced by MGM. FOOTNOTE 5. The two Duncan Maclain movies are of a particular Hollywood type – the light mystery movie with doses of comedy– that flourished in the thirties and forties. Light mysteries could be found on radio as well. NBC’s The Adventures of the Thin Man ran from 1941 through 1948. The series was modeled after the Nick and Nora Charles movies rather than Dashiell Hammett’s novel. Another good example of the radio detective series with humor is Dick Powell’s Richard Diamond, Private Detective (1949-1953). Detective series were very popular in movies, radio, magazines, and books. They especially abounded in the pulps, a reflection of the popular culture at the time. A number of detective series overlapped in many of the mediums of the era – pulps, books, movies, comics, and radio. Examples include The Saint, Philip Marlowe, Nick Carter, Philo Vance, Charlie Chan, and Sam Spade. The Jeffery Wren series was written for Dime Detective when Hollywood and radio were at their heights, before television had its devastating impact on both mediums and on the viewing and reading habits of the public. The similarity of Wren to Edward Arnold was undoubtedly an attempt by Fleming-Roberts to increase the character’s appeal by linking him to a popular Hollywood actor. Jeffery Wren is a confirmed bachelor, and has a fear of being entrapped by predatory women, especially widows. He lives in a hotel suite somewhere in Indianapolis, and usually leaves it promptly at 8:30 AM to catch a bus to his downtown magic shop, arriving there within a half hour. He doesn’t have a driver’s license, and doesn’t seem to have an automobile, but he does know how to drive. Wren doesn’t carry a gun, but comes across them in his investigations and can use them effectively. He uses sleight-of-hand a number of times to deprive people of their guns. He likewise uses magic tricks when questioning people, sometimes pulling a rubber ball from someone’s mouth or making cigarettes appear from nowhere. He may also use his magical expertise when he needs to distract attackers so he can defend himself. Wren has an intense dislike of spiritualists. He is the author of a book entitled The Dead Don’t Talk, an expose on fraud spiritualism. He mentions in the stories that it is “a notoriously poor seller.” He also works with the Indianapolis police in cleaning “spook crooks” out of the city. Fraud spiritualism was used to good effect in the pulps. A good example is Walter Gibson’s early Shadow novel “The Ghost Makers” (10/15/32). FOOTNOTE 6. Jeffery Wren is hired occasionally as an investigator of spirit mediums and other so-called occultists because his detective ability is known. He invariably becomes involved in cases of murder tinged with occult mystery. None of these turn out to be truly supernatural; all have a rational explanation. This is a fallback to the basic idea behind many of the weird-menace stories of the thirties, where supposedly supernatural occurrences were almost always rationalized away. As G. T. Fleming-Roberts himself wrote many stories for the weird-menace pulps, he was very familiar with this style of plot. The first Jeffery Wren story was “No Haunting Allowed” (4/44), and the characters are naturally not as well-developed as in the later entries in the series. Wren mentions at the beginning of the story that it is his first murder case, calling it “My baptism in murder. Or call it a ducking.” The victim is murdered in the magician’s presence and Wren almost becomes victim number two. As is usual in each of the series’ stories, money is at the root of the murder. “The Spirit Was Willing” (8/44) is the second story. It involves a crooked medium who has avoided legal troubles by maintaining “The Church of Life Everlasting” and taking contributions rather than charging fees. The medium’s assistant is murdered and the motive is unknown. As mentioned earlier, the third story, “A Sleight Case of Murder” (10/44), introduces homicide detective Sergeant Thomas Hogan, probably injected to add a little more conflict into the series. The plot involves a missing elderly woman, a disappearing body, a seance, a spirit hand made from paraffin, blackmail, and a rooming house full of strange characters. “Scare a Man to Death” (1/45) is the fourth story of the Wren series. The magician suspects that a supposed locked-room suicide is actually murder. The victim had written several wills, leaving his fortune to a different person in each document. He even leaves his money to Satan in one of the wills. The ingenuous murder method in this story is described in an article Fleming-Roberts published in the April 1951 issue of Writer’s Markets and Methods. According to this essay, the author and his wife spent an entire evening working out the murder to make certain it could actually be done. Fleming-Roberts often used inventive murder methods in his stories, but seemed to choose ones that could actually occur. In the fifth story, “He Couldn’t Stay Dead” (5/45), Wren is involved in a case of murder where a large inheritance is at stake. This story has an unintentionally humorous aspect to it due to the placement of several advertisements. The first victim is murdered by means of a poisoned tobacco pipe. In the original printing of the twenty-five-page story, there are two advertisements for competing brands of tobacco pipes. A funny coincidence, but did the advertisers see it as such?  “Medium Dead” (11/45) is the sixth story. It begins on a hot July day. Wren is hired to investigate strange happenings among the wealthy Oakley family. The patriarch of the family is acting very odd and has been supposedly playing tic-tac-toe with a ghost. This scene is portrayed on the cover of Dime Detective, showing an old, stern-looking man playing the game with a skeletal figure while a young woman in the background looks on in fear. In “Feather Your Coffin” (10/46), the last story in the series, Wren has become well-known as a trouble-shooter of unusual mysteries. This story begins with a locked-room murder with no body. Those involved ascribe the events to a poltergeist, something the magician-detective sets out to disprove. FOOTNOTE 7. At the time of the Jeffery Wren stories in Dime Detective, the magazine published many continuing series featuring various kinds of detectives. Many of these characters were quite unusual and did not fit the usual mold for pulp detectives. Jeffery Wren fit right in with these oddballs. For example, in the October 1944 issue of Dime Detective there is not only the Wren story, “A Sleight Case of Murder,” but also a Bill Brent story by Frederick C. Davis and an Inspector Alhoff story by D. L. Champion. Brent is a romance columnist involved in criminal investigations while Inspector Alhoff is an eccentric, ill-tempered, bad-mannered crank who is missing both of his legs. Other unusual pulp detective characters in Dime Detective during 1944-1946 included Lawrence Treat’s Edward Asa Scott, an artist who investigates murders, T. T. Flynn’s Mr. Maddox, a traveling racetrack bookmaker, Dale Clark’s “High” Price, a private eye, and D. L. Champion’s Mariano Mercado, a Mexican private detective who wears outrageously colored clothes and is a hypochondriac. G. T. Fleming-Roberts wrote many hero and detective stories for the pulps. In addition to Jeffery Wren, quite a few of the author’s detectives practiced the art of magic. The series featuring The Ghost/Green Ghost is the best known. The longer stories in this Thrilling pulp gave the author room for a good deal of story development. Later, the Green Ghost yarns were about the same length as the Jeffery Wren stories and some aspects of the series were left out due to space considerations. In an article published in the May 1943 issue of Writer’s Digest, Fleming-Roberts discusses how he came up with an idea and plot for a Green Ghost story: Recently, in working out one of the Green

Ghost

mystery stories which I do for Leo Margulies, I found myself with a

deadline to meet and nothing in my head but a title — a crazy bit of

alliteration, “The Case of the Bachelor’s Bones.” The title

obviously suggested that some unfortunate bachelor would be murdered,

possibly burned so that there would be very little left of him but his

bones. Applying the reverse reasoning method, I immediately

pulled away from that first inspiration. In the end of the yarn I

would reveal that a pair of dice the bachelor owned would be much more

important than his skeleton.

This started me on some research into the subject of loaded dice, and this, in turn, suggested that my unlucky bachelor would be a gambler. A dishonest gambler, since he was using loaded dice? Not at all, not at all. Make him an honest gambler and then figure out why he would be using loaded dice. From that point on I was off along a bumpy side road that led to one of Mr. Marguiles’ phenomenally fast checks. The six-story Diamondstone series, published in Standard’s Popular Detective from 1937-1939, preceded the Jeffery Wren series and is quite different. The action in the Diamondstone series is much faster and the stories are more violent. There is a physical resemblance between the two characters, but Diamondstone is considerably younger and much more agile than Wren. Diamondstone also seems to have some similarities, none of them physical, to George Chance, the Ghost. He is a professional magician who retired young and wealthy like Chance. He only takes cases that interest him and does not charge a fee. Whereas the Ghost frequently uses disguises, Diamondstone and Jeffery Wren never do so. The last of the Diamondstone stories appeared in the June 1939 issue of Popular Detective. With Standard’s The Ghost debuting with the January 1940 issue, most likely the Diamondstone stories were discontinued in favor of the new series. As late as 1947, G. T. Fleming-Roberts had a story published in which the main character was a magician who ran a magic store. He was not a detective as was Jeffery Wren, but was forced by circumstances to investigate a crime. This twelve-page story, “Slay ’em in the Aisles!” appeared in the October 1947 issue of Popular’s Detective Tales. It seems the author could not let magician-detectives go without at least one more story. There were other magician-detectives in the pulps, Walter Gibson’s Norgil and Clayton Rawson’s Don Diavolo being two of the best known. FOOTNOTE 8. So Jeffery Wren did have some company. Although G. T. Fleming-Roberts’ character didn’t have a long run nor attract as much attention as his fellow sleight-of-hand artists, he was a detective different than most and a well-thought-out character worthy of more stories. _______ FOOTNOTE 1. Indianapolis as a site for this series was not just a random choice. Fleming-Roberts was born in Lafayette, Indiana in 1910, and moved to Indianapolis in 1934. He lived there for over ten years, so he knew the city well. He seems to have had a fondness for setting stories in either Indianapolis or somewhere in Indiana, as many of the hundreds of stories he wrote are placed there. FOOTNOTE 2. Alan Havig (1990), Fred Allen’s Radio Comedy, page 30, Philadelphia: Temple University Press. FOOTNOTE 3. To get a good idea of what vaudeville was like, look for the PBS American Masters special “Vaudeville.” FOOTNOTE 4. Gardner, as A. A. Fair, wrote 29 Bertha Cool novels between 1939 and 1970, including two per year during 1940-42. A total of nine adventures featuring Cool and Donald Lam, her partner, had appeared through 1944, the year the Wren stories debuted in Dime Detective. FOOTNOTE 5. Captain Maclain, blinded by gas while serving as an intelligence officer in World War I, was created by Baynard H. Kendrick. The stories were inspired by a blind Canadian soldier the author had met during the First World War. The character debuted in 1937 in the novel The Last Express (filmed by Universal a year later). Kendrick wrote ten more books featuring Maclain, including a 1947 collection of short stories entitled Make Mine Maclain. According to William DeAndrea’s Encyclopedia Mysteriosa (Prentice Hall, New York, 1994), “The tall and handsome private eye is a man of action and, with and without the (seeing eye) dog, prevails in numerous fights” (page 222). FOOTNOTE 6. Spiritualism was very popular earlier this century, especially with such proponents as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes. Many people believed in the ability of spiritualists, and many such believers were well-educated people. FOOTNOTE 7. This story has an inside joke that only those readers familiar with Fleming-Roberts’ pulp-detective stories would catch. He has Wren mention a detective agency based in Indianapolis named the Oberron Agency. Pat Oberron was the lead of another Fleming-Roberts detective series whose one-man agency was based in the Hillary Building, a seedy building with eccentric tenants, all of whom are on the make for a fast buck. These stories appeared in Popular Publications’ Big-Book Detective and New Detective. FOOTNOTE 8. Gibson’s Norgil stories were published under the name of Maxwell Grant and appeared in Street & Smith’s anthology title Crime Busters. The Don Diavolo or Scarlet Wizard adventures were attributed to Stuart Towne when originally published by the Frank A. Munsey Company in Red Star Mystery. Comment: This article first appeared in slightly different form in Purple Prose #13, November 2000. Thanks to Mike Chomko for agreeing to its appearance here. Back in the fall of 1988, pulp fan and historian

Albert Tonik hopped into his motor home to tour the country and search

out its pulp roots. One of the stops along his way was Nashville,

Indiana, home to the law office of James T. Roberts and to Agatha Reed,

James’ mother and the former wife of writer G. T.

Fleming-Roberts. Albert had been led to Nashville by a letter

from Roberts published in the sixth issue of DC Comics’ The Shadow,

dated August-September 1974. He described his visit to

Nashville in Tom and Ginger Johnson’s Echoes

43, published in June 1989.

“Nashville is a quaint town with an artist colony and tourists walking the main street shopping in all the boutiques. Jim said he would lead me to his mother’s house. He jumped in his Corvette and zoomed out of sight. When I rounded a curve in the road, he was waiting for me. The Roberts had lived in a beautiful house built out of rough hewn logs, called the Witch House because it resembled the witch’s house in the illustrations for “Hansel and Gretel.” Agatha has since remarried to Dick Reed. “Five years after Tommy (G. T. stood for George Thomas) died she had destroyed his records, but kept his magazines in an old steamer trunk. I went through the six hundred magazines, put them in chronological order, and copied the table of contents.” In addition to compiling a bibliography of the late author, Al Tonli also conducted an interview of the woman he had married in 1939, the former Agatha Halcyon Amell, Mrs. G. T. Fleming-Roberts, later known as Agatha Reed. The interview was recorded on September 17, 1988 at the Witch House, the home of Agatha and Richard Reed. A WRITER’S WIFE

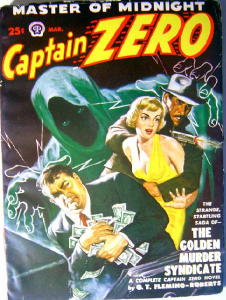

A Interview with Mrs. G. T. Fleming-Roberts conducted byAlbert Tonik. Introduction by Monte C. Herridge. G. T. Fleming-Roberts was one of the workhorses of the pulp era, from his first story publication in 1933 to his last fiction appearance in Manhunt in 1955. Although not as prolific as Walter B. Gibson, Erle Stanley Gardner, Frederick C. Davis, and others, he wrote hundreds of stories of all lengths, managing to become known enough to have his name placed on the covers of many of the magazines he appeared in, often with cover illustrations devoted to his stories. G. T. Fleming-Roberts was born George Thomas Roberts on April 17, 1910 in Lafayette, Indiana. His father was George Roberts, a Professor of Veterinary Surgery at Purdue University, the school where his son later acquired his Bachelor of Sciences degree. Intending to become a teacher, it was by happenstance that George Thomas Roberts became a writer. After graduation and awaiting word on his application for a teacher’s license, G. T. wrote four detective short stories on a broken typewriter. After all four were rejected, he sought advice on what he had done wrong. He looked up an agent to help him. His entrance into the pulp field was greatly aided by this agent – August Lenniger – who showed the budding author what he needed to do to write salable stories. In return, Lenniger received a small commission for every story sold. The renamed G. T. Fleming-Roberts – the author had added Fleming as a middle name, while his agent had added the dash – never dealt directly with the publishers and editors; Lenniger did so for him. FOOTNOTE 1. Fleming-Roberts was a lifelong Indiana native, only leaving the state for short trips and one involuntary time away. This extended absence was from the summer of 1945 to January 1946, when he was in the Army Air Corps and stationed at Sheppard Field, Wichita Falls, Texas. To someone acclimated to Indiana, Texas must have seemed like the end of the earth. His widow recalled how he disliked the air base and refused to let her live there while he was in the service. He disliked snakes, though he was not afraid of them. Probably one reason he did not like Texas was its many snakes. Fleming-Roberts’ primary field of writing was mystery and detective fiction, along with the related fields of weird menace and the hero pulps. The stories he wrote for all of the genres were basically mysteries, and this was what he wrote best. From what is known of his work, he wrote only three pieces that did not fit these related genres. One was the non-fiction article in 1943 for Writer’s Digest, “A Turn from the Trite,” about how he thought up ideas for his stories. Another was his one science-fiction story, published in the December 1940 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories – “The Golden Barrier.” However, even in this story he found it difficult to escape his area of expertise and interest; the main character is a policeman of the future trying to solve a crime. The third piece is a short aviation story set during the Second World War. “Trinidad Pay-Off” was published in the September 1943 issue of Fighting Aces. It appeared under a Popular Publications’ house name – Ray P. Shotwell; interestingly it appeared under his own name in the Canadian edition of this pulp in its March 1945 issue. Fleming-Roberts had his own special writing area in his home in order to concentrate on his work. In his Writer’s Digest article he described it as follows: During the past ten years, I have had my

workshop on the second floor of my home, on the first floor, and, at

this writing, I am relegated to the basement. So far as I know,

there is nothing lower in this life. I think I could play this

into something emotional – me, cast into the basement like an old

anything after ten years of faithful service – but to be perfectly

honest, this is a very nice basement with a supposedly sound-proof

ceiling, knotty pine walls, an asphalt tile floor, fluorescent

lighting, comfortable furniture. It has an all but invariable

temperature the year round, and I like it.

Probably the reason he had moved to the basement was because his son, James T. Roberts, was born in 1941. Fleming-Roberts lived in Indianapolis from 1934-1947. He had married Agatha Halcyon Amell in 1939. In 1947 the family, including his mother, moved to Nashville in Brown County, Indiana. There new home was a rustic cottage built of square, rough-hewn logs called “The Witch House.” The Roberts decided to call it that because of the quaint resemblance to the gingerbread and candy house of the witch in the tale “Hansel and Gretel.” Brown County was and still is known for being populated by writers and artists. At his new residence, he had a special building out back where he did his writing. According to an article in the Indianapolis Star Magazine for December 21, 1947, Fleming-Roberts scheduled his writing work, probably in order to be disciplined enough to be a success at writing stories that had to meet editors’ and publishers’ deadlines. “For twelve years Roberts wrote from 8 to 11:30 each morning, 12:30 to 4 each afternoon, and 6 to 10 each night. Sundays included. Eleven hours a day.” After his service in World War II, he reduced his workload to seven days a week, days only, and produced 24 stories a year. His marriage to Agatha Amell was an instance of his determination to succeed at something, much like his writing career. He had to campaign hard to convince her to marry him. She refused to marry him at first, and he had to work at it. He depended upon his wife considerably to assist him in his writing career. An article described her as his “chief literary critic and advisor.” She also took care of unpleasant things such as snakes. He always called for his wife to take care of them when he encountered them. Curiously, for a mystery writer, he mentions in connection with killing snakes: “I just can’t stand to kill anything,” he says. “I never could.” In 1939 he began writing a new pulp hero series for Standard Publications. Even though the reasons are not known for his appointment as the author of this new pulp hero series about “The Ghost,” he was a natural choice. He had already demonstrated he could write a series of “novels” by doing the Secret Agent X series from 1935-39 for Ace, and his series featuring Diamondstone, another magician-detective, for Standard was exactly in the same vein as the Ghost series. Fleming-Roberts also penned the short-lived Black Hood series for Blue Ribbon/Columbia in 1941-42, Captain Zero for Popular in 1949-50, and a trio of Dan Fowler stories for Standard’s G-Men Detective. “Blackmail With Feathers,” a 34-page story published in the August 1942 issue of Detective Novels, was one of his more successful stories. It was made into a movie by Warner Brothers in 1943 – FIND THE BLACKMAILER – starring Jerome Cowan and Faye Emerson. A 1946 film, LADY CHASER (also known as LADY KILLER), starring Robert Lowery, Ann Savage and Inez Cooper, was based upon the 22-page story “Lady Killer,” published in the July 1945 issue of Detective Tales. Supposedly a third story was also made into a movie, but information about this is not presently known. FOOTNOTE 2. Another successful story was “Married to Murder,” published in the July 1945 issue of Argosy, and reprinted in the hardback anthology Best Detective Stories of the Year in 1946. One interesting aspect of Fleming-Roberts’ writing career was the frequency of stories set in Indiana – often in Indianapolis. Both the Jeffrey Wren and Pat Oberron series are both placed in this city. His familiarity with his home state no doubt led him to do this. After all, it simplified his work to place his stories in familiar surroundings he could describe with ease. FOOTNOTE 3. Fleming-Roberts’ stories are easy to read; the plots are understandable, not far-fetched or nonexistent like some others. He seems to have thought them out a bit more than those pulp writers who seemed to have the idea that if they put enough action in their stories, the plot holes (or total lack of a plots) would not be noticed. Fleming-Roberts did research and in some cases tested his murder methods in order to ensure that his stories would be plausible. He was aided by his collection of technical books on medicine, crime, and police science. Fleming-Roberts wanted to ensure that his stories were interesting to his readers. In the Indianapolis Star Magazine article, he explained: The menace nowadays has to be something

common and familiar… Adults are reading the magazines – kids

dropped them in favor of comic books – and you can’t scare grownup

mystery readers with a slinking figure in a black cape or a nasty old

clutching hand.

He clearly knew something about magicians; his many stories about magicians hold up fairly well, though not always perfectly. With the pulp market fading, Fleming-Roberts had to find other ways of making a livelihood. It is unknown why he did not move into the original paperback market like other pulp writers. Instead, he spent a portion of his time in the early 1950s touring and lecturing on how to write. He also became involved in politics in Brown County, Indiana, serving as county chairman of the Republican Party. He gained a position as bailiff of the United States District Court, serving until his death in October 1968. At the present time, a small number of his stories have been reprinted in various forms. Hopefully all of them will eventually be reprinted and saved from being lost with the eventual disintegration of the pulp magazines themselves. Previously unknown Fleming-Roberts’ stories are still occasionally found. Two of the “Captain Zero” stories were never published, but the manuscripts supposedly exist in an unknown person’s possession. That would be a great event if these two lost stories could be discovered and published for the first time. An unpublished story of his, entitled “Suicide Squad,” is in the Street & Smith archives at Syracuse University in New York. THE INTERVIEW (conducted on September 17,

1988)

(Al) Tonik: When was Tommy born and when did he die? (Agatha) Reed: He was born April 19, 1910 in Indianapolis. He was the second child. There was an older sister, Margaret. She was twelve or thirteen when Tommy was born, and her nose was out of joint the rest of her life. He died either the 5th or 6th of October, 1968 – almost twenty years ago. Tonik: When did you meet him? Reed: I met him in 1939 in Marshall, Michigan. He was visiting his friend, Lewis Storr, who was also a writer. In fact, he was the fellow who collaborated with Wallace Cook … is that the person?…to write Plotto. FOOTNOTE 4. Both of them lived in the same town. Lewis’s wife is the girl I call my sister now. They came over and picked me up and we spent the whole day together. We went on a fifty mile trip. I was in the back seat with Chet Harrison and Janet. Lewis and Tommy were in the front. I was in a real giddy mood and chattered my head off. That seemed to appeal to Tommy. Tonik: How old were you at the time? Reed: Twenty-six. Tonik: He proposed to you when? Reed: That night. He did! I don’t know … he must have been in the mood. I did not accept. Then he started to write me letters – beautiful long letters. Just recently, I have burned them. So finally, I accepted. He gave me a ring, a silver and baroque pearl engagement ring, until he could get me the diamond, which I am saving for my granddaughter. Later, I got an even more beautiful diamond ring. The writing business was not that good. Some of these were family jewels. In fact, my biggest diamond was out of his own ring. He decided he no longer wanted to wear it. We were married in my home church in Lansing, Michigan – the Church of the Resurrection. I took a long time to organize it, because I had to get dispensation from the Pope to marry a non-Catholic, a Presbyterian. I saw him only four times before I married him; we only had four dates. Afterward, we lived in his house in Indianapolis for six years before we moved here. Tonik: Did you help him with his writing? Reed: No, he did it all on his own. He used to ask me to correct his spelling. I was a better speller than he. Tonik: Did he take trips to New York to see his editors? Reed: Yes, he did, but only two times. One time before we were married and one time after we were married. That is all. He did not care to travel. I went with him on the second trip. We were house guests of his agent, August Lenniger, and his wife, Beatrice. They had a house in Scarsdale that was very, very lovely. We were there ten days. That was an extremely long visit, but they had a lot of business to take care of. Tonik: Did you go into New York with him on his visits to editors? Reed: No, I was wrapped up in caring for our little son. There was no one to leave him with. Tonik: How old was Jimmy then? Reed: He was about six. Jim was born in December 1941. We moved here in 1946. We went to New York in 1947. One day, the three of us, without any of the people we were visiting, took the train into the city. We were going to see the Statue of Liberty. We were just about to get on the ferry boat when Tommy said he had this appointment downtown. He left me with this little kid in a place I had never been before. I had been taught to respect a policeman. So you just ask a policeman what to do. FOOTNOTE 5. Tonik: That’s what I learned too. Reed: Yes, the one I asked was intelligent and he told me where to go. We jumped on the ferry. Jim and I did all the things you are supposed to do. We climbed the Statue. When we got back, that is when I did not know what to do. There was a tour bus. I figured that should take us somewhere. It took us to Grand Central Station. As I look back, I don’t know how we ever made it! Tonik: When did the strange incident (you previously mentioned) happen at the Lennigers’ house? Reed: That was two or three years after our visit with them, probably in the fifties. We got a very long letter from them explaining this horrible event. They had gone to Canada on a fishing trip. Their housekeeper came in everyday from eight to five, except on weekends. She was a large lady with a marked English accent. I never did know what she said. She was cute. She was not a drinker, but she got into the liquor and got roaring drunk. She demolished the Lennigers’ master bedroom suite – a big room with fireplace, dressing room, bath, and small sitting room on the second floor. It was extensively damaged – draperies ripped, mirrors smashed, furniture broken. She locked herself in the suite and that’s where Beatrice’s brother and the police found her. She drank herself to death! Tonik: According to my research, Tommy stopped writing about 1950. Reed: About 1952 – closer to the time he was a delegate to the National Convention which was 1952. He had become involved in local politics. He was Republican county chairman in this county. Under his guidance the Republicans got an officer in the courthouse for the first time in 125 years. FOOTNOTE 6. Tonik: Was he paid for being county chairman? Reed: No, but he was paid for being bailiff to the federal judge. Earlier than that he worked in the Department of Education. Tonik: He was bailiff for fifteen years until he retired? Reed: He never did retire. He was actively at work at the time he became ill. He was in New Albany. I was 58 and he was two years and a few days older than me. It was a great life. We had a wonderful life together. Tonik: Tommy went into the service during World War II. Reed: Yes, it was while we were still living in Indianapolis. He went in the summer of 1945, and he was discharged in January 1946. We saved his Christmas gifts. They were all wrapped up. When he came home, January 16th, we had a small Christmas just for him. It was shortly after that we began looking for a place in the country. Tonik: Where was he stationed in the service – Washington, D. C.? Reed: No, it was Wichita Falls, Texas – a horrible place, the end of the earth. Tonik: Everybody feels that way about where they are in the service. Reed: He refused to let me join him, ever. He said conditions were deplorable. He would not want neither me nor our child to be exposed to that situation. So we stayed home. Tonik: Did he do any writing while he was in the service? Reed: No, but he was always assigned to something that had to do with the typewriter. And he was sort of a father-confessor to all the young guys. He was, golly, thirty-five at the time. His mother stayed with us. I wrote him every day. He wrote nice letters, which he was especially skilled at. Tonik: Did August Lenniger convince Tommy to do certain series? Reed: I don’t know. Oh, he must have influenced Tommy with what the market needed. Tonik: Around the time you met him, he was doing a series called “The Ghost.” Reed: Oh, yes. “The Ghost” went with us on our honeymoon. He took a typewriter and said he had to get this in. He said that’s the way it is. But he didn’t write a word. He never opened the typewriter case. Tonik: Then he did something with “The Black Hood.” Reed: Yes, I remember that. It sounds familiar. Tonik: You don’t remember any problems with writing any of these stories? Reed: He always had to cut. Frequently they were sent back and Tommy had to shorten them. Tonik: “The Black Hood” was especially interesting because it came from the comic books. Did Tommy have to go and buy a bunch of comic books for research? Reed: Comic books were just one of our regular reading materials. And with our little boy. FOOTNOTE 7. Tonik: So he probably knew about the character, “The Black Hood,” before he started writing about him. Reed: Yes, I was hoping I could find the magazine with the story that he wrote with the Brown county background. One of the characters in Captain Zero was the girl friend, Doro Kelly, a cute, blue-eyed blonde. S he was modeled on one of our neighbors in Indianapolis – Eudora Kelly. The editors tried to convince Tommy to create a whole army of invisible men for Captain Zero, but Tommy refused. Tonik: Let me ask about Chet Harrison. Do you know when they met? FOOTNOTE 8. Reed: He and Tommy? I really don’t know. Jetta, my sister, may know more about that because Chet and Tommy and Lewis Storr were chums – through the mail, primarily. Tonik: At the time, did Chet Harrison live in Indianapolis? Reed: They were very close. They lived in the same neighborhood. They organized the “Coffee and Curses Club,” for the local writers, which met once a month. Tonik: Do you remember when Harrison moved to Los Angeles? Reed: It was probably about 1948 or 1949, because Chet and Nancy and their children visited us here in Brown County. Very shortly, their children would be ready for college. They went out there so they could be educated. Otherwise, they would not have been able to afford to send them to college. Tonik: So he earned his living as a writer, also? Reed: Yes. Tonik: Do you know when Tommy met Merle Constiner? FOOTNOTE 9. Reed: I don’t know how he met them or when, but we visited the Constiners in their home in Monroe, Ohio. It must have been 1943 or 1944, because we were still living in Indianapolis and we took Jimmy with us. It’s a small town halfway between Dayton and Cincinnati. It was excruciatingly hot. Their house was on the main highway – fifty feet from the highway. The traffic was terrible even back then. The back yard was beautiful. It was not a fancy house and the plumbing was not operating. We had to stay at the next-door neighbor’s house. The lady let us have a room there. Jim wouldn’t eat at mealtime. In the middle of the night he wouldn’t sleep, and he was hungry, and it was so hot. But it was a nice visit. I liked Merle a lot. He was a charmer, but a recluse. He would not step out of the house. He worked all the time at writing, just like Tommy. They were devoted to their craft. Chet was too. Merle’s wife, Suzanna, never washed dishes except once a week. She had tons of beautiful china. She had a pantry, an eight by ten foot room with shelves on all sides. She washed the silver after every meal, but the china, just once a week. She was a girl from the deep South, a southern belle. At dinner, her linen was gorgeous, her meals excellent, but while eating, a cute little mouse would run across the floor, under your feet. Suzanna died ahead of Merle. She had a lot of eye problems. She showed me pictures of herself as a little girl, getting off the boat with the side paddle wheels after coming up the river to Cincinnati for eye treatments. Tonik: Tommy and Merle corresponded with one another? Reed: Yes. Tonik: Do you remember any other people that Tommy corresponded with? Reed: No, I don’t. Tonik: Did Tommy stay with Lenniger through his entire writing career? Reed: Yes, he did. Tonik: He never sold directly to editors? Reed: I don’t believe he did. They were good friends. Tommy never had any real problems with Lenniger. Tonik: Did Lenniger ever send back stories and ask Tommy to rewrite them? Reed: I believe so, because we frequently were in the thralls of redoing a story. Most of the time, his stories were too long for what the magazines wanted. I can remember that distinctly. Tommy did not like to do that. He would rather have written a little more. August and his wife came to visit us in Indianapolis. They spent a nice, five-day visit. Tonik: Was this before or after you visited them? Reed: This was after we visited them. Tonik: Thank you, Agatha. = Agnes Reed passed away on December 8, 2002, at the age of ninety. = FOOTNOTE 1. Margaret Fleming was the maiden name of G. T. Fleming-Roberts’ mother. FOOTNOTE 2. Fleming-Roberts’ Jeffrey Wren appeared in Popular’s Dime Detective while the Pat Oberron yarns ran in Big-Book Detective and New Detective, both Popular pulps. FOOTNOTE 3. According to James T. Roberts, the author’s son, his father always claimed that the first film based on his work, FIND THE BLACKMAILER, made Faye Emerson a star. A popular leading lady during the forties, some of Ms. Emerson’s more notable films include BETWEEN TWO WORLDS (1944), THE MASK OF DIMITRIOS (1944, with a screenplay by pulp author Frank Gruber) and HOTEL BERLIN (1945). She made her television debut in 1948, and for the next fifteen years was often seen as a guest on that medium. FOOTNOTE 4. James T. Roberts was told by Lewis Storr’s daughter that her father was not a writer, but that he was a close friend of William Wallace Cook, another resident of Marshall, Michigan. A prolific author for the dime novel and pulp magazine markets, Cook was also the author of Plotto, a book which aided with plot construction. It was first published in 1928. According to Roberts, Plotto was used by many pulp authors, including his father. [Personal communication with James Roberts, June 21, 2003.] FOOTNOTE 5. According to James Roberts, his mother wrote the date the family moved to the “Witch House” on the basement wall – June of 1946. FOOTNOTE 6. Fleming-Roberts’ last original story was published in Manhunt in 1955. FOOTNOTE 7. Jim Roberts told Tonik that his father did not like him reading comic books, except the Walt Disney variety – certainly not the superhero type. FOOTNOTE 8. Chester William Harrison (1913-1994), whose usual byline was C. William Harrison, sold his first story in 1936. He primarily wrote for the Western field, selling 1200 stories to Big-Book Western, Dime Western, Frontier Stories, Ranch Romances, 10 Story Western, Texas Rangers, Wild West Weekly and other titles. He also wrote sports, science fiction, love stories and about fifty detective yarns. The latter found homes in such magazines as Detective Tales, Dime Detective, Dime Mystery, Private Detective and Ten Detective Aces. During the fifties, Harrison turned to the original paperback field, writing over a half dozen novels for a variety of publishers. His book The Guns of Fort Petticoat, published by Gold Medal in 1957, was turned into a motion picture by Columbia. Released the same year, it starred Audie Murphy and Kathryn Grant. FOOTNOTE 9. Merle Constiner (1902-1979) sold his first story around 1940. A graduate of Vanderbilt University, Constiner wrote about one hundred stories for the pulps, primarily in the detective, Western and adventure fields. He is best remembered today for his stories of the Dean, a tough detective who appeared in around twenty issues of Popular’s Dime Detective Magazine. Another series, featuring private eye Luther McGavock, ran in Black Mask. Constiner also wrote for Adventure, Argosy, Blue Book, Short Stories and other pulps. During the fifties and early sixties, he turned to the slicks, selling to the American Magazine, Collier’s, Country Gentleman, the Saturday Evening Post and others. He also began to write original paperbacks, publishing over a dozen in this form. An exceptional biography of Constiner, written by Peter Ruber, appeared in Camille Cazedessus’ Pulpdom 19, published in September 1999. NOTE: This interview, along with

Monte Herridge’s informative

introduction, first appeared in slightly different form in Purple Prose 17 (July 2003),

published by Michael Chomko. Thanks to Al, Monte and Mike

for allowing its appearance online here.

DURING the past ten years, I have had my workshop on the second floor of my home, on the first floor,and, at this writing, I am relegated to the basement. So far as I know, there is nothing lower in this life. I think I could play this into something emotional – me, cast into the basement like an old anything after ten years of faithful service – but to be perfectly honest, this is a very nice basement with a supposedly sound-proof ceiling, knotty pine walls, an asphalt tile floor, fluorescent lighting, comfortable furniture. It has an all but invariable temperature the year round, and I like it. In this my latest workshop I meet a nice class of people – men who read meters, change over oil burners, and the plumbers who unclog the drains. Each and all, at one time or another, have discovered that I have no keeper; have learned that I am down here for the bloody business of writing murder yarns. Some have been kind enough to say they have read my stuff. And after that comes the inevitable question: “Where do you get your ideas?” I get the same question from beginning writers. But asked wistfully. The plumber is never wistful, because he knows when he’s well off. But the beginning writer is always wistful and will frequently add to the inevitable question, “Editors tell me my situations are trite. What’s the rule for avoiding the trite?” I asked Merle Constiner whose characters people the pages of Black Mask and Dime Detective regularly. “After the ten-year stretch you’ve served at writing,” Merle replied, “you just naturally avoid the trite like poison ivy.” The same question addressed to C. William Harrison, who generously spreads his talents over the entire western and detective fields, brought the following: “You don’t avoid the trite. You use it and give it a new coat of paint.” Both are right, of course, but neither is particularly helpful to the beginner. Let’s consider the subject of a doorknob – that now famous glass doorknob Arthur J. Burks told us all about in the Writer’s Digest many moons ago. Mr. Burks was demonstrating how he could take any object in his hotel room and produce a plot idea from it. Glancing at his glass doorknob, he conceived the idea that a valuable diamond could be concealed in it, and therein was the nucleus of a detective story plot. I distinctly remember that after Mr. Burks discovered the possibilities of his doorknob, the entire detective field became cluttered with stories concerning stolen diamonds concealed in anything of cut glass from Lady Windfall’s punch bowl to Milady’s perfume bottle stoppers. In imitation of Burks’ doorknob, I thought up a honey of a stunt. It came in a flash at the dinner table just as I was about to wolf a dish of lime gelatin. Why not conceal emeralds in a dish of lime gelatin? That little bit of dinner table inspiration netted me one of the few absolutely unsaleable duds on the pantry shelf. But I learned something. I learned that while Arthur Burks could write from inspiration, I couldn’t. And I further decided that the average detective story reader on reading a. yarn that concerned a stolen diamond and a cut glass doorknob – or lime gelatin and my own gem – comes to the identical conclusion that the inspired writer did when the idea first hatched: that the diamond is in the doorknob. Whenever I am struck with something like that diamond-doorknob gag, right there is where I make an abrupt turn. I set the idea aside, put a gift card on it labeled, “Ixnay Icksiepay.” Then I start off across uncharted wastes, seeking an entirely different significance for the doorknob. Call the method “reverse reasoning” if it has to have a name. I have no patent on it, and I’m convinced that all professional detective story writers use it. Merle Constiner has never said anything to me about using reverse reasoning, but watch that author’s mental gymnastics carry him far away from the trite in the McGavock yarn “Why Meddle With Murder?”in January Black Mask. It’s a doorstop we are concerned with this time – not a doorknob. Merle’s doorstop is a red, carpet covered brick which immediately attains importance in the story by being mentioned in somebody’s will. Stolen jewelry also figures in the yarn. I’m willing to bet that when Author Constiner first hit upon a carpet covered brick doorstop as his plot nucleus, it occurred to him that such a doorstop would make a swell place to hide something of value. Exactly the same idea would have struck the beginning writer provided he happened to stumble over the doorstop in the first place; so it might be said that beginner and professional start out with the same equipment. Some ten thousand or so words after the doorstop has been introduced and dangled intriguingly in front of the reader’s eye, Merle’s detective, Luther McGavock, gets his hands on the doorstop, rips the carpet covering off, and reveals what’s inside. The stolen jewels? Oh, no. Beneath the covering is the last thing the reader – or the beginning writer – would think of – an honest to heaven, common alley variety of brick. And on that brick the author builds his highly original and logical conc1usion. How many packs of thoroughly smoked cigarettes went into the ash barrel before you got that solution figured out, Merle. Anyway, Merle Constiner’s brick demonstrates the reverse reasoning process. It is essentially a simple stunt, consisting of discarding the first easy-come inspiration and getting right down to using the old think tank. You can use the trite idea if you reverse it – thus the reader comfortably expecting that he has outguessed you, is utterly fooled. THE amateur writer doesn’t lack novel situations at all. He simply refuses to work out solutions to those situations, even discarding valuable material because there is no easy solution filed away for ready reference. In fiction, no situation is without a possible and logical solution. Any tantalizing situation that you hit on can be explained, and in leisurely working out this explanation, you may unfold your story. To find that solution frequently means much back-tracking and revising to replant a means for the solution. But the result is frequently gratifying and not apt to be trite. Back to Burks’ doorknob for a moment, because the darned thing haunted me for years. I finally decided that the only way to lay the ghost was to write a doorknob murder yarn of my own. I started with a brass doorknob, just to be different. Since doorknobs are generally found on doors, reverse reasoning prompted me to put mine somewhere else. The tapered cylinder of a paper drinking cup would, I decided, hold a doorknob very nicely. The most logical reason for the doorknob being in the Lily cup seems to be that this particular doorknob is plastered with latent finger prints and whoever put the knob in the cup did so to keep the finger prints from being smudged, believing he could get the cup out before it dropped to passerby. Immediately the whole course of the story practically falls into my lap. There will be murder and its motive will be blackmail. My victim will be the man who put the knob in the cup and the finger prints on the knob will be blackmail evidence. Naturally, the man whose finger prints are on the knob is the person who is being blackmailed and he will also be the murderer. Fine! A nice broad highway, straight to the conclusion. But right here is where I turn off. Let the reader take the broad highway while I jog off along a bumpy sideroad. I devise another motive for murdering the man who put the knob in the cup, do plenty of mental back-tracking to supply the necessary clues and plants. When the pay-off comes, my detective can carry the reader right through to the solution of the blackmail angle, clear up the business about the doorknob, get right up to the thoroughly obvious villain – and then pounce on the actual murderer to disclose a greed-jealousy motive instead of the fear motive suggested by the blackmail angle. No, it wasn’t particularly easy, competitor-to-be, but Popular Publication’s Alden Norton made my efforts worth while. Recently, in working out one of the Green Ghost mystery stories which I do for Leo Margulies, I found myself with a deadline to meet and nothing in my head but a title-a crazy bit of alliteration, “The Case of the Bachelor’s Bones.” The title obviously suggested that some unfortunate bachelor would be murdered, possibly burned so that there would be very little left of him but his bones. Applying the reverse reasoning method, I immediately pulled away from that first inspiration. In the end of the yarn I would reveal that a pair of dice the bachelor owned would be,much more important than his skeleton This started me on some research into the subject of loaded dice, and this, in turn, suggested that my unlucky bachelor would be a gambler. A dishonest gambler, since he was using loaded dice? Not at all, not at all. Make him an honest gambler and then figure out why he would be using loaded dice. From that point on I was off along a bumpy sideroad that led to one of Mr. Margulies’ phenomenally fast checks. Let’s see if the reverse reasoning method will furnish that new coat of paint for a thoroughly trite situation as C. William Harrison has suggested. Now, as probably everybody knows, there’s no device which has been used any more frequently in detective stories than the murder committed inside the locked, practically hermetically sealed room. It is still a good gag, and there must be a number of as yet unexplored ways in and out of that sealed room. But in a yarn I was working on not so long ago, I found myself with a locked room, a dead man inside it, and no new way up my sleeve for getting in and out. In fact, I had used the very old gag of working the lock from the outside by means of a piece of. thread manipulated to turn the key on the inside. Unfortunately, the gag had to come quite near the beginning of the story. I felt certain that if that old hackneyed situation could be saved, the rest of the yarn was sure money. There was my detective and a number of other people standing outside this room in an office building, and everybody, including the reader, was perfectly aware there was a corpse in that room. There had to be a corpse in there, or my story was a dead duck. Detectives, as you’ve probably noticed, have a couple of tried and true – and trite – methods of getting into locked rooms. They smash the panel with burly shoulders – or maybe it’s the more logical fire ax – or they pick the lock. My shady detective was more the lock-picking, skeleton-key type. But instead of doing the expected, my detective simply looked at the door and said, “To hell with it. If I open that room now, every time some rat nest of an office in this building is burglared, I’ll get the blame.” Arid he walked away. Disappointing to the reader? I don’t think so. I think that turn from the trite saved a situation that might otherwise have ruined an acceptable story. There is some truth in the beginner’s frequent complaint that he cannot recognize the trite unless he has done a great deal of reading and writing, but if he accepts this premise as gospel he immediately errects an insurmountable barrier for himself. So far as basic situations are concerned – and by basic situation I mean the tested formulae of the “boy meets girl” variety – there is certainly nothing new. But the beginner has in William Wallace Cook’s “Plotto” a complete list of all these basic formulae, and all of them, as stated in “Plotto” are trite, since they were taken from published stories. Erle Stanley Gardner uses this storehouse of plots one way; but to me, “Plotto” is an excellent text on what is trite – a book which. beginners should carefully study before they decide to sell it to pay the grocery bill. Let’s pick a typical “Plotto” formula, examine, and see what can be done with it as a springboard for a complete skeleton plot. For example, try paragraph 819, page 111: “A, a burglar, seeks to aid B, who was his friend before he went to the bad.” A, friend of B, breaks into a building for the purpose of committing robbery, and finds a trusted employe, A-5, B’s husband, dead at his desk, a defaulter and a suicide. A-5 has left a note explaining his guilt. A, in order to save his friend B from disgrace, destroys the letter that would have proved B’s husband, A-5, a defaulter and suicide, ‘blows’ a safe and pretends to have committed a robbery.” I think everyone must know that a detective story based upon straight suicide is highly disappointing to the reader, so let’s make that our first important change. The death of A-5 is framed to look like suicide by X, a murderer. A, completely taken in by the framed. evidence of suicide, reframes the scene to look like murder without being aware that it actually is murder. Thus, a different basic situation-and a more intriguing one-begins to show up. Let’s tinker with it some more. Instead of making A a burglar, why not make him an ex-burglar? Why not make B a girl who befriended A after A “went to the bad,” that is, after he got out of prison? We shall not meddle with the self-sacrifice behind A’s dead, because that is good for an emotional pull, but as the motive for that deed now stands it can be strengthened considerably. Instead of making B the wife of A-5, let’s make her a sister of A-5. Suppose that B is being wooed by A-2 scion of a wealthy and aristocratic family. A is also secretly in love with B, to give us a triangle with B at the apex and A and A-2 at the other two points. We can explain A’s secret passion for B on the grounds that A’s devotion to the lady coupled with A’s “past” leads him to the conclusion that he isn’t good enough for B. On discovering that A-5 is apparently a defaulter and a suicide, A decides to frame the job as robbery and murder in order to save B from disagreeable publicity which might make her unwelcome in A-2’s family. But what about the love triangle in a detective story? Its easiest solution – and the first to pop into the designing author’s head – is that one point of the triangle may be disposed of by making that person the murderer. Since we are presumably beginners and can’t know that such treatment of the triangle is trite – trite to the point of being a taboo in some editorial offices – we must trust reverse reasoning and decide at once that A-2 cannot possible be X, the murderer. We can play up to the reader’s natural thought process by making A-2 look like the murderer. We might do this by revealing in the course of the story that A-S is blackmailing A-2, thus providing substantial motive for A-2 to have done the job, but under no circumstances must A-2 turn out to be X. Let’s revise the old Plotto formula to include the changes we have made: A, an ex-con, seeks to aid B whom he loves and who has befriended him since A got out of prison. A discovers A-5, B’s brother, dead in an office, apparently a defaulter and suicide. A, in order to save B from disagreeable publicity which would wreck her romance with A-2, member of an aristocratic family, frames the scene to appear as robbery motivated murder, little suspecting that it is actually a case of murder, and that A will be chief suspect in the eyes of the police. There is a new basic situation from which any number of new plots may be built. Consider its possibilities. When it is revealed that the job is actually murder, A must, in self defense, find the real murderer. How is A to get rid of the supposed suicide weapon? Shall robbery be the real motive for the killing? How is the love triangle to be broken down in order to achieve a happy ending? Shall this be accomplished by making A-2 a second murder victim about the time the reader has decided that A-2 is the murderer, or shall we let A-2 to be suspected to the very end of the story? Ask the questions and settle upon the least obvious answers. Bring in material bits of “business” such as doorknobs or what-have-you. Chances are, you’ll have too much fresh material for a single story. It won’t be easy, but then, friend competitor-to-be, plotting a detective story never is. This article first appeared in Writer’s Digest, May 1943.

A FINAL NOTE: Several of the pulp cover images are courtesy of Phil Stephensen-Payne and his Galactic Central website. If you are a fan or collector of pulp magazines, or for that matter fiction magazines of any kind, this is a site you should not miss. YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. All material not from the Writer’s Digest copyright © 2006 by their authors, Monte Herridge and Albert Tonik. Return to the Main Page. |