THE POWER OF PLACE: THE RECLUSIVE WORLDS OF

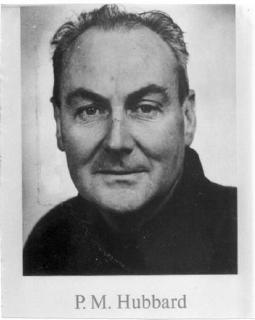

P. M. HUBBARD - by Tom Jenkins

British novelist P. M.

Hubbard builds his suspense slowly and incrementally, as anticipation

and foreboding dominate the unfolding of his plots with the perpetual

possibility of the “uninvited.” British novelist P. M.

Hubbard builds his suspense slowly and incrementally, as anticipation

and foreboding dominate the unfolding of his plots with the perpetual

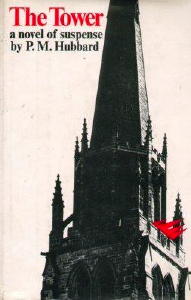

possibility of the “uninvited.”The little-known mysteries of Philip Maitland Hubbard, written from 1963 to 1977 in England and Scotland, and found today mostly in libraries, are startling in their focus on setting or place, incremental evocation of suspense, and verbal minimalism. His interior monologue narration allows the telling of his tales from an intense personal point of view. The result has become his metier: a quiet but pervasive suspense. The settings are mostly rural and remote outposts where upper-middle class or professional people live in small towns, villages or isolated houses in secluded woods, along the coast, or in the Highlands. The often lonely and always mysterious house or landscape is the objective correlative of the hero/narrator’s state of mind. Each book has only three or four main characters, with the focus on the protagonist from whose frame of reference the story is developed. Their vital relationships to one another, often with the narrator falling in love with an inaccessible woman, one in imminent danger, or restricted by some family obligation, are irrevocably linked to their settings. The denouement is an integral part of place. The power of place. In a letter written 27 years ago, Hubbard clearly explained his view of setting. “The place is generally, in fact, the central character of the book. I start with one or two characters necessary to carry the theme, and then I just start writing and see what happens,” he explained. “Fresh characters introduce themselves, existing characters do unexpected things, and the story just goes on growing. I do occasionally go back and change a few details which no longer fit, but it’s odd how seldom that happens. This is because the story is conceived and built up as an organic whole all tied to the place. The later parts fit the earlier parts because they have developed naturally out of them. Even the final solution is not imposed from the outside, but it is the explanation of all that has gone on before.” His solution could only happen as it did in that particular place. The Causeway is a gothic in both nature and structure. It has a mysterious island on the west coast of Scotland, with an equally mysterious house on it, connected to the mainland only by a low-tide causeway. There is another lonely house on the mainland in which lives a reclusive couple. Peter Grant, sailing his small boat in unfamiliar waters, is forced ashore to become accidentally involved with the couple, falling in love with the woman and precipitating events which lead to violent death. The cast of characters is small, but there is a mythic pattern arising from the bleak setting. In The Tower, a traveler, John Smith, comes upon a small English village in which a fanatic fire-and-brimstone Anglican priest is creating a curious kind of folk liturgy. Finding the village obsessed by the 18th century St. Udan’s Church tower, which is threatening to collapse, and attracted to a woman who lives there, Smith stays and becomes a “catalyst to many things,” wrote Anthony Boucher [NY Times Book Review, 5/28/67] “including a murder plot. The characters are unconventional but real; there is an almost Arthur Machen creepiness to the village and its culture.” Christian happenings cannot obscure the pagan ritualism of a Saints Day festival and a nearly lethal bonfire before the town’s dilemma is resolved.  Entitled with a perfect

metaphor, A Hive of Glass

focuses on a glass collector, Johnnie Slade, who along with others, is

desperately trying to find a missing, rare-as-Rembrandt, Venetian

tazza. Tantalized by the rare beauty of the stolen Verzelini

goblet, Slade goes to a small seacoast town and an isolated house where

he finds an enchanting woman and an inevitable sudden detah.

“This novel set in a decaying English town has a curious, dark gothic

feel to it,” explained Boucher, [NY

Times Book Review, 9/5/65] “and should provide, for all its

irony and wit, a few genuine shudders.” Entitled with a perfect

metaphor, A Hive of Glass

focuses on a glass collector, Johnnie Slade, who along with others, is

desperately trying to find a missing, rare-as-Rembrandt, Venetian

tazza. Tantalized by the rare beauty of the stolen Verzelini

goblet, Slade goes to a small seacoast town and an isolated house where

he finds an enchanting woman and an inevitable sudden detah.

“This novel set in a decaying English town has a curious, dark gothic

feel to it,” explained Boucher, [NY

Times Book Review, 9/5/65] “and should provide, for all its

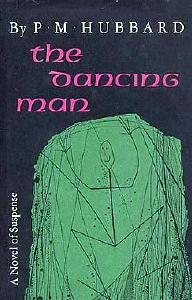

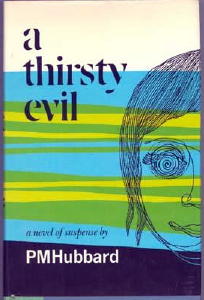

irony and wit, a few genuine shudders.”The Dancing Man is the epitome of Hubbard’s limited cast of four characters, sparse dialogue, and intriguing plot complexities, all intertwined with the setting of an isolated Victorian house in northern Wales, as Mark Hawkins comes to search for his missing brother. Dick, his brother, had been concerned with prehistory and megalithic monuments, but Mark’s host Merrion is interested in only the Medieval Period and the Cistercian Abbey that once stood near his house. As Mark’s detection evolves, he learns about the megalithic pillar on Merrion’s land which has the carving of a dancing man (a clue), and he falls in love with his host’s sister, all leading eventually to the revelation of murder and a horrific ending. Evocation of suspense. Anthony Boucher wrote of Hubbard’s direct and terse narrative style. “Avoiding clichés as much as possible, interested in people yet devoid of sentimentality, without even any overt physical action, Hubbard can suggest untold horror in a few deft passages.” In The Causeway, for example, fearing discovery by the reclusive and maniacal Barlow, Grant approaches it from the sea. “I scrambled to the top of the bank, and suddenly Barlow was standing on the slope not fifteen yards from me. Then he turned and and looked at me. It was not Barlow at all ... and for a moment we looked at each other, and then he smiled. It was if a skull had suddenly grinned at me.” In each of his books there is an unnerving anticipation of violence as Hubbard’s interior monologue builds the tension page by page. The antagonists’ potential for violence is held in abeyance until usually late in the book, or at the end. Their capability for violent action is just below the surface of things. British writer and bibliophile Anthony Quinton says, “Hubbard succeeds in investing everyday circumstances and the commonplace functions and rituals of daily living with a shapelessly menacing quality.” [London Times Literary Supplement, 8/27/76]. There is minimal brutality, physical confrontation, and even death, but even more, the threat of these is always present, the suspense evoked by the narrator’s concerns, the worry and fear of unseen presences and implied dangers, and never far away, the possibility of the uninvited. At the brink of the final denouement and discovery in The Dancing Man, Hawkins faces the possibility of confronting his brother’s killer but not yet seeing him. “This time I heard the noise of the leaves. It came quietly at first. I could not have heard it at all if the silence had not been so complete. It grew louder ... getting nearer ...” Later, at the novel’s end, he finally comes face to face with the murderer, and a quiet but violent death takes place. Throughout each novel, scene after scene contains unpretentious, seemingly unimportant events which build slowly and resolutely to the final conclusion. In The Graveyard, the feared antagonist, Davie Bain, seems to threaten the life of Mary with whom the hero figure Ainslie is in love, after coming to the remote snowy hills and crags of nothern Scotland to help cull the deer herds. Ainslie tries to help her search for an incriminating box buried in a secret place in a country graveyard without being discovered by Bain, who is intent on killing her. The hunter becomes the hunted as the circle of tension tightens until the climax of discovery and death.. Likewise in The Whisper in the Glen, the focus is on a deceptively calm surface of a small highland village where long-held secrets are ultimately revealed, and an ironic death on a mountainside seems to justify old wrongs. Kate Wychett (the heroine) takes a teaching post in a village invested with ancient clan animosity. Caught up in the local milieu, she becomes enmeshed in the tangle of desires and jealousies of the small town. Ultimately, death on a mountainside rights old wrongs.  Similarly in A Thirsty Evil, novelist Ian Mackellar’s obsessive love for beautiful Julie is stymied by a four-sided relationship between the members of a dysfunctional family living in a West Country English village and a dark pond in the secluded woods near the family home. Below the surface of the pond lurks a tragedy, which acts as a metaphor of the slowly developing conflict that arises between the four people. Again, Hubbard uses penumbrous and moody atmosphere to evoke his aura of suspense. Verbal minimalism. Hubbard’s prose is of extreme plainness and simplicity of word choice, free from adjective fat and excessive authorial verbiage. His novels seem to tell themselves through the eyes of his protagonists, and major imaginative effects are produced by the most economical means. “The main character comes before the reader,” says Quinton, “with very little in the way of supporting information, without much of a past, free from any encumbering involvement with people or institutions.” In this way Hubbard concentrates on the immediate present, focusing on the narrator’s current concerns and objectives, and of course, mounting fears as he proceeds with the tale he is telling. It is a kind of verbal minimalism without extraneous descriptions or asides. It is straight and simple. In The Causeway, there is a perfect example of the minimal ideal expression: “I do not know at what hour of the night it was, but she came to me (to my bed) at last. I think she came for comfort and much more than comfort. We even found a little sleep.” Four words: “... much more than comfort.” How could it be said any simpler. In A Hive of Glass, Hubbard describes the rare old Italian goblet: “The miracle of its creation is almost superseded by the miracle of its survival.” And in The Dancing Man, the discovery of a twelve-foot-high stone pillar, massive and foreboding with markings high up on one side: “Someone had carved a human figure, a matchstick man sketched in single strokes but still horribly alove. It danced on the stone holding its stick-like arms over its head and kicking its legs outward, its enormous penis stiffly in front of it.” A major clue in the novel, it had once been a crucifix, and later someone had transformed the cross into “this happy little ithyphallic manikin. It was consciously and deliberately devilish.” A rare use of vocabulary for Hubbard, but still simple. In High Tide, ex-con Peter Curtis travels across England and then sails up the coast to a seaside village, where he finds an apparently deserted house on the tidal flats. Here his love relationship with a beautiful woman develops, along with tension and eventually a murder. Once again the terror rises slowly, in a once peaceful yet vulnerable setting. At one point halfway through the novel, a scene at night illustrates Hubbard’s potent use of words. “Helen was standing against the wall, sheltered from the wind in the full light of the moon. She came across and took me by the hand, and we went down the path leading from the garden. The path dropped until we were out of sight of the house, and then we stopped and made love on the grass in the moonlight, with the wind blowing our clothes all over the place.” Conclusion. As an author, P. M. Hubbard is an original. His writing is comprised of an idiosyncratic and sympathetic vision of people as he knows them in the British isles and how they interact. Anthony Quinton referred to this mixture as “a kind of imaginative transcription into the idiom of theBritish middle-class about the presenta-tion of the self in everyday life.” Beyond the “unmistakable surprise and erotic geniality,” as he puts it, “his group of people are bound together by a sharing of assumptions that makes communication effective even when imperceptible.” Except, of course, when it goes awry. Hubbard knows the difference, and he can weave his tales involving each, and here is where the tension arises. His simple words of force and clarity do the job. BIOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND: Philip Maitland Hubbard was born in 1910 in Reading, Berkshire, England. Because of his father’s health, the family moved to the isle of Guernsey, where Hubbard acquired his knowledge and love of the sea. After attending Elizabeth College there, he became a classical scholar at Jesus College, Oxford (B.A. and M.A.), where he won the Newdigate Prize for English verse in 1933. From Oxford he went into the Indian Civil Service in northwest India (now Pakistan), where he remained until 1947. He returned to England to work for the British Council in London for four years. He resigned to become a freelance writer, contributing verse, feature articles and Parliamentary reports to Punch magazine, and also served as a director of the National Union of Manufacturers. He left and then devoted himself to full-time writing, producing sixteen suspense novels, some children’s stories and some other works of fiction between 1963 and 1979. Hubbard lived in Thomas Hardy country – Dorset – before moving to southwest Scotland in 1973, where he lived until his death on March 17, 1980. He was separated, but he stipulated in his will that his wife receive a pension and “live in Horsehill Cottage in Dorset undisturbed in any way” and that a trust be established for his son and two daughters. LETTERS FROM P. M. HUBBARD TO TOM JENKINS

Hunts Barn, Mayfield, Sussex 28th January, 1973. Dear Mr. Jenkins, Thank you very much for your two letters. The second in fact arrived before the first, which had been badly misdirected at one point (in this country.) I am glad my books give you pleasure. You are right, of course, in picking on the English as their main virtue. I say they are not very good books [but] beautifully written. I have too little sympathy with other people to be a good novelist (a general male failing, which is why most of the great novels are written by women), but my English rests on a severely traditional classical education, which I have no doubt is the only sound basis for using English properly. Millie has long since disappeared from the marketplace here, I am afraid. It is a book I am rather fond of myself, but perhaps the least successful of all mine. In America it came out from Maxwell–London House. From the next one, Hive, Atheneum took over, & they have published my books in America ever since. I’ll see if I can find a spare copy here somewhere, but I’m not hopeful. (And by the way – you never enclosed a copy of the Library Journal review, as you said you would. I should like to see it. Ancient history now, but his reported preference to Millie over Hive interests me.) As for poetry, I am to be thought of as poet manqué rather than a poet. Most of my “serious” poetry has remained unpublishable in my period, because it rhymes and scans. I write a good deal of verse for Punch between 1950 & 1962. Of course a lot of comic, satirical, topical & occasional stuff, but occasionally, when the editor wasn’t looking too closely, lapses into poetry (as I see it.) If you can get hold of the bound volumes for those years, say in a public library, and look up my name in the index of authors for each year, you ought to be able to turn up quite a lot, though I don’t know what you’ll make of it. It is spread over a period of changing tastes, changing views and changing editors. I tell you what. I’ll enclose a copy of a (virtually unpublished) short poem which embodies, as I know it, the poetic (and indeed general literary) experience – as against the, e.g., T. S. Eliot’s perpetually complaining of the inadequacy of words. Give it to your students, without comment, and see what they make of it. They can’t, after all, look it up. Thank you, again, very much for writing. Yours sincerely P. M. Hubbard ==========================================

THE WORD The idiot who proudly says, “I sought The word to clothe my thought. My thought was very noble, and the poor word tries To make it visible in vain” – Does not so much confess To mental nakedness, As have the lie in his soul, ignorant that he lies, Irredeemably profane. But let a man confess he does not know What importunes him so, Something not of himself, which cries outside his door; Let him admit it as of right, Not claiming for a moment to create. Let the man only wait. The word itself will come, and what he had before Will wither in its light. ===========================================

HUNTS BARN, MAYFIELD, SUSSEX 12th March, 1973. Dear Mr. Jenkins, May I try simply to answer your specific questions (put in your letter of the 1st February)? First my lack of sympathy with other people. By this I mean that I am in myself a egotist, and tend to see people mainly as factors in my own situation, whereas I should have thought that a novelist must (or at least on occasion be able to) take a God’s-eye view of them. Of course all fiction writers are egotists, and a certain degree of egotism is necessary to impose a unity on their imagined world and people. But they ought to be able to envisage other people’s feeling more clearly than probably I can. As to my planning of a book, the plain answer is that I don’t. I have some general theme in my head, and I marry that to a place (always imaginary, but imagined to the last detail and compass-point). The place is generally in fact the principal character in the book, because, again, places mean more to me than people. However, I start with the one or two characters necessary to carry the theme, and then I just start writing and see what happens. Fresh characters introduce themselves, existing characters do unexpected things and the thing just goes on growing. At some point, obviously, I have to stop and say, in effect, “Well, what is this about? What really is going to happen?” But I may be two-thirds of the way through the book by then. Even then I don’t conceive the solution in more than general terms, but of course the further I go, the more precisely I can see ahead. I do very occasionally have to go back and change a few details at the start of the book which no longer fit its outcome, but it is odd how seldom this happens. This is because the thing is conceived and built up as an organic growth. the later parts fit the earlier parts simply because they have developed naturally out of them. Even the final solution is not something imposed from the outside, but is precisely the explanation of all that has gone before. In detail, I write very much as it falls out, writing in my own minuscule hand (700+ words to a quarto page), and changing very little, and that only for purely verbal reasons, so that you may get several consecutive pages of ms. with no corrections at all. When I have finished, I copy it out laboriously on my typewriter, and the result is the text as printed. I cannot consider such a thing as a re-draft, because once the book is down on paper, it is dead so far as I am concerned, and a postmortem may be possible, but not surgery. The next book is due out this summer (June, I think). It is called A Rooted Sorrow (Macbeth, as you will recognise), and is about guilt as much as anything. The one I am just finishing is called A Thirsty Evil (Measure for M.), and is about obsession. Hope this rather scrappy letter may be of some use and interest to you. Yours sincerely, P. M. Hubbard THE NOVELS OF P. M. HUBBARD - An

Annotated Bibliography by Wyatt James.

The Gothic novel is much older than the detective story, although there has always been an amount of mystery in the genre. P. M. Hubbard did not have a series detective – in fact he rarely had a detective in the true sense at all, although his protagonists often made deductions – but his books can be classified as mystery novels with a large admixture of the “Gothic,” always involving greed, passion, and homicide as well as grotesque horror, a tried and true amalgamation that has always been a sub-genre of mystery fiction. His greatest skill was in startling the reader by throwing in a sudden shock in the midst of some clean, straightforward prose (much like J. Sheridan Le Fanu and Richard Hughes, author of A High Wind in Jamaica, for example): “Levinson sat at his desk in the middle of

the room, looking at me with his usual small, curiously sweet

smile. A thin coil of smoke wound upwards from the cigar resting

on the edge of the ash-tray at his right hand. The whole room

smelt of it. His hands were on his lap.

Note, as an aside, the narrator’s basic indifference

to the fate of poor Levinson, but rather an egoistic reaction as to how

he was affected – most of Hubbard’s protagonists are basically amoral

and self-centered. Another of Hubbard’s characteristics is a

great skill in describing an outré environment, usually

involving an unpleasant landscape with mud, overgrown trees, and

rotting smells. In fact, he overdoes that as one will find on a

marathon read – one can only take so much of stinking tidal mud-flats

bordered by a sinister wood. And he tends to be depressing; one

needs to be in the mood for that.“I said, ‘Good evening,’ and then saw that something was not quite right. I had moved, but his eyes had not. He was warm, composed and friendly, but quite dead. “I cannot stand dead and broken things....” [from A Hive of Glass] Although he is not strictly a detective-story writer, Hubbard was admired by critics as varied as Boucher and Barzun, and was lauded by “mainstream” critics for his wit, clean prose style, and characterization. He counts as a “Golden Age” author, not for when his books were written, but for when he was born, because he was a contemporary of many of the late classical mystery writers. He is definitely one of the best of the mystery writers of the 20th Century. British hardcover editions are listed first, followed by the US edition. [* superior, ** superb] Flush As May. Michael Joseph, 1963. London House & Maxwell, 1963. US paperback: Ballantine, 1964. A good debut, based on the hoary old device of somebody out for a walk discovering a dead body, which then disappears. There is something sinister going on in this English village, built along a prehistoric ley line. Pagan survivals and a conspiracy of silence, as of course one might predict. Nicely done, though, even if so subtly that nothing seems to happen. * Picture of Millie. Michael Joseph, 1964. London House & Maxwell, 1964. An atypical Hubbard (well-adapted characters with little malice or amorality). The story has the death by drowning at a seaside resort village (middle-class boatsmen) in the West Country of a visiting vampish woman; the men in her life here are well described. Although there is no suspicion of murder, we, as readers, of course know better. The author shows his skill at one-liners (e.g., “There couldn't be any eternal triangle with the Trents. It was more like a perpetual polygon.” Also “...he saw Mr Menloe was smiling. The effect was slightly ghastly, as if the Hound of the Baskervilles had suddenly wagged its tail.”). Another plus is also his fine descriptive abilities when it comes to landscapes and environment. In this case, for example, an excellent description of an excursion by fishing boat under the cliffs on a fine calm day that to the reader is an actual experience. What is also intriguing is how the victim was perceived and regarded differently by the other characters, hence the title. Slow-starting, but an exciting ending, with a scary scene on the cliffs and a real surprise at the end of the book. (Unusually for this author, the protagonist is a police detective, someone we readers would have liked to meet again, who is on vacation.) ** A Hive of Glass. Michael Joseph, 1965. Atheneum, 1965. Reprinted in hardcover, Hamish Hamilton (UK), 1972. UK paperback, Panther, 1966. Johnnie Slade, while sybaritic as to sex and food, is an obsessed collector of antique glassware (as are his closest friends). We all know how fanatical collectors behave when they sniff out a new morsel; there is no surprise that this is what happens in this book. With a vengeance. One of the best efforts in the mystery genre on this theme, with many scenes of gruesome violence, evil and obnoxious characters, and unpleasant settings (the seaside “village” of Grane). The female co-protagonist is an excellent example of another person driven to amoral behavior and egoism (in her case, involving greed, hatred, and a sexual penchant for older men). There is a scene when the hero, while driving the two of them down a dark road at night, hits and kills a deer being chased by a giant hound, and our dear Claudia goes after the dog with the bloody torn-off antler out of sheer wantonness. The ending, in an abandoned mine, is gruesome and exciting. A great book. ** The Holm Oaks. Michael Joseph, 1965. Atheneum, 1966. Unrelentingly creepy and depressing. There is something that will haunt you forever about the fate of the hero’s wife in the dark holm oak copse behind the flat seashore, where she goes at night to hunt the wild nicticorax (a bird that sounds like someone vomiting) with her tape recorder, not knowing that their hostile neighbor has introduced a herd of feral Tamworth pigs, particularly revolting animals, into the wood. The final sentence reads: “I stumbled ... along the beach, with the empty gun in my hands, full of a growing consciousness of total and intolerable loss.”  The Tower. Geoffrey Bles, 1968. Atheneum, 1967. Reprinted in hardcover, Detective Book Club (US) [3-in-1], n.d. Set in a rather backward English village (Coyle), and involving a vicar who is an Anglo-Catholic religious fanatic, his efforts to raise money to save the monstrous bell tower from collapse, local gentry, publicans, etc. There is a nice set-piece involving the October bonfire festival, a pagan survival the vicar has preempted into some sort of medieval saint's festival, at which there is an attempted murder; and a nice bang-up ending, when the tower collapses. Otherwise, with a death but no murder, this is a rather dull book – all atmosphere with little plot. * The Custom of the Country. Geoffrey Bles, 1969. Atheneum, 1969, as The Country of Again. This book is set in post-Raj India, and is a great complement to the “Jewel in the Crown” series: well-recommended although not as a detective story. The contrast between what the English expected of the rule of law back in the “Golden Age” and what happens now is very effective. No doubt, Hubbard's experience in the Indian Civil Service is reflected in this novel. It involves a visit by an English ex-district-judge who worked there before Independence/Partition (pre-Pakistan), and is caught up in old local politics and modern corporate activity in repercussions from an old murder that happened during his period of administration. Class differences, new vs. old, the vendetta mentality, and a cynical nostalgia – all are involved (and a nice, subdued inter-cultural love affair). Cold Waters. Geoffrey Bles, 1970. Atheneum, 1969. This one is set on a remote island in an unspecified loch in Scotland, with only five people, including the narrator and two women (his employer's wife and a maid), both of whom, this being that sort of Hubbard hero, he sleeps with. The narrator is one of those cynical, depressed, but over-curious types the author does so well. While this does not rank as best Hubbard, it is enjoyable, the menace creeps up (something to do with spies), and the ending is abrupt and violent. Water and isolation are the recurring motif, as it so often is with this writer. * High Tide. Macmillan, 1971. Atheneum, 1970. Reprinted in hardcover, Detective Book Club (US) [3-in-1]. Newspaper supplement, Toronto Star Weekly, August 8, 1970. US/UK paperback, Perennial, 1982.  A good little thriller. The hero, Curtis, large and bad-tempered, but still a Hubbard sort with an interest in books, sailing, and unusual women, has just come out of prison after serving a sentence for wrongful death (the victim had run over the hero's dog and in a rage Curtis man-handled him a bit, causing a fatal heart attack). He decides to go “walkabout” by car to the West Country, driving all night, sleeping at inns by day. It turns out he is being followed, and the mysterious and genteel “Mr Matthews from Surbiton” eventually confronts him and asks what the manslaughter victim had said when he was dying. Curtis doesn't remember, and that seems to be it. But he is curious, and now recalls the words “high tide at --:--” (same numbers as the license plate on his old car). He now decides to investigate, and perhaps find a profit in what the victim was so urgently trying to obtain. But of course the villains haven't given up... The book also has a well-described and interesting setting along the cliffy south coast of Devon, and some good single-handed sailing. ** The Dancing Man. Macmillan, 1971. Atheneum, 1971. Reprinted in hardcover, Mystery Guild (US) [book club], n.d.; Ian Henry (UK), 1980. UK paperback, House of Stratus, n.d. A novel of obsession, this time archeological: a medievalist vs a prehistorian. It has a wonderful setting in the hills of rural Wales: an isolated house, a ruined Cistercian abbey, and a neolithic ring larger than Avebury, ... and pagan gods and ghosts. This is Hubbard’s most creepy environment to my taste (speaking as an aficionado of the ancient Celts). There is a small but well-presented cast of intelligent characters (most of Hubbard's people are highly intelligent no matter how crooked or messed up they might be), including the village loonie, the mad professor, the sexy wife, and the enigmatic virgin sister with whom the protagonist becomes obsessed. There is also a nice M. R. Jamesian set-piece involving the translation of a 9th Century Latin church edict. And, as usual, an exciting and creepy ending. * The Whisper in the Glen. Macmillan, 1972. Atheneum, 1972. A Scottish Highlands setting: a married couple in a rut move from London up to Scotland for the husband to take a job teaching in a rather third-rate boys’ school. She becomes obsessed with the local laird, and her dealings with the sinister “stalker” (gamekeeper), the primitive and hostile Gaelic wife of the headmaster, a gay phys-ed instructor who is an excellent photographer, and various locals. “Whisper in the glen” refers to the highland bush telegraph – everybody is so cut off and bored that other people's business is the main interest in life, along with Celtic mores and a feudalistic attitude. The scenery is gorgeous but daunting (steep hills and sudden mists). There are some amusing observations about the Highland folk, Gordonstounish schools, and holiday camps. (The gymnast's comment when he shows her a “candid” photograph he happened to take of Catriona and her Heathcliff up on the fells: “Cheer up. I expect even Helen of Troy looked pretty silly with her legs in the air.”) Chapter 15 has a very well-done adult conversation that is all the more convincing by being conducted over the telephone. There is a quick and violent climax when dark secrets are revealed. This is strictly a romance novel with some perceptive and striking moments, but a good job is made of it.  A Rooted Sorrow. Macmillan, 1973. Atheneum, 1973. The protagonist is an author with writer's block – depressed (and depressing) and obsessed to near immobility, though he fusses a lot, cleaning dirty dishes immediately after use, etc. He withdraws into his country cottage, which he had fled “mysteriously” five years before, gets re-involved with the locals and old friends, and behaves rather oddly. A so-called “novel of suspense” (the catch-all phrase that critics use when they can’t specify more detail), and pretty dull reading for Hubbard. A gloomy book, and talky, too. But there is, at least, a somewhat unexpected ending. A Thirsty Evil. Macmillan, 1974. Atheneum, 1974. A writer becomes obsessed with a very unforthcoming woman; she has two kid siblings (Beth and Charlie) who are monsters of one sort or another. Is one of them evil, or just a lunatic? The creepy events take place in an artificial 18th Century “folly” pool or lake with a sinister underwater rock spire called The Mole. The countryside is pleasant hill country, with an ancient round barrow as well as the lake, but there is little involvement with the villagers – this is strictly a small-cast affair. Brooding, as always, and the protagonist works himself into a state of helplessness as often happens in a Hubbard book. A characteristic book by this author, although not outstanding. * The Graveyard. Macmillan, 1975. Atheneum, 1975. Reprinted in hardcover, Book Club Associates (UK), n.d. Set in the Scottish Highlands, with a very simple plot: a secret buried on a hillside, sought after by a villain and a pretty young lass with the help of the narrator. The description of the area around the loch with its know-everything inhabitants, the fickle weather of near winter, the gorgeous but treacherous scenery – it is all wonderful. The toilsome business of culling deer herds is portrayed so brilliantly that one becomes fascinated with a nasty occupation. The ending is abrupt and saddening. A good story, if weak on plot. * The Causeway. Macmillan, 1976. Doubleday [Crime Club], 1978. The author is very good when it comes to describing small-boat sailing, as in this book. The protagonist is a farm-machinery salesman in southwest Scotland, who is an enthusiastic sailor. He runs aground on a small off-shore island (with a muddy causeway to the mainland exposed only at low tide) and becomes involved with an eremetical couple with a deep secret. Of course he falls in love with the wife and is terrorized by the taciturn husband. What is the secret on the island? A simple but violent solution reveals all. The Quiet River. Macmillan, 1978. Doubleday [Crime Club], 1978. Reprinted in hardcover, Book Club Associates (UK), n.d. This next-to-last effort of the author’s is a rather tired effort that repeats earlier themes – what is it about Hubbard and water? – involving an uncomfortable marriage, the relocation of a London couple to a remote house in the country, a sinister local farmer of the Mellors sort, and some creepy moments amongst mist and flood. This countryside lacks any aspect of the picturesque – dull, flat, agricultural land somewhere in the Midlands, with an unpleasant river winding through it. As in the better Whisper in the Glen, the point-of-view character is the wife. One recurring motif is isolation, both physical and mental. The story is in no traditional sense a mystery. Kill Claudio. Macmillan, 1979. Doubleday [Crime Club], 1979. This final novel is not much more than an extended novella. Beyond its simple plot, however, it is a fine example of the British hunter-and-hunted theme, as exemplified by The Thiry-Nine Steps. It involves a pair of ex-spies – or international crooks, take your pick – after an unspecified treasure buried some twenty years before after a shipwreck on the Island of Jersey (or perhaps Guernsey). Very well done, with some nice descriptive prose and nasty moments such as a cat-and-mouse adventure in an empty train. The title refers to Much Ado about Nothing, in which Beatrice's first request to her new lover Benedick is to “Kill Claudio.” Here, the amoral hero, a night watchman, is asked by the widow to whom he is attracted to kill the murderer of her husband. P.M. HUBBARD’S OTHER WRITINGS, compiled by

Tom Jenkins and Steve Lewis.

Ovid Among the Goths [poetry], B. Blackwood, Oxford, 1933. Anna Highbury [children’s fiction], Cassell (UK), 1963. Rat Trap Island [children’s fiction], Cassell (UK), 1964. “Dead Man’s Bay” [radio play], 1966. Short Fiction [excluding poetry] ● Manuscript Found in a Vacuum [short story], The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (F&SF), Aug 1953. ● Botany Bay [short story], F&SF, Feb 1955. ● Lion [short story], F&SF, Mar 1956. ● The Golden Brick [short story], F&SF, Jan 1963. ● Special Consent [short story], F&SF, Oct 1963. ● The Shepherd of Esdon Pen [short story], F&SF, Feb 1964. ● Last Time Lucky [short story], The Tandem Book of Ghost Stories, Charles Birkin, editor, Tandem (pb), 1965. Book published in the US as The Haunted Dancers, Paperback Library, 1967. ● Cash on Delivery [short story], Argosy (UK), Jan 1969. ● The House [short story], F&SF, Apr 1969. ● Soft Drink [short story], Argosy (UK), May 1969. ● Bed and Breakfast [short story], Argosy (UK), Feb 1970. ● Mary [short story], Winter’s Crimes 3, George Hardinge, editor, Macmillan (UK) 1971. ● The Running of the Deer [short story], Winter’s Crimes 6, George Hardinge, editor, Macmillan (UK) 1974. ● Leave It to the River [short story], unknown original publication, 1978. Reprinted in Murder Most Scottish, Stefan Dziemianowicz, Bob Adey, Ed Gorman & Martin H. Greenberg, editors, Barnes & Noble (US), 1999. SOURCES: The Internet Speculative Fiction DataBase William G. Contento “Mystery Short Fiction” Phil Stephensen-Payne (private email) Dennis Liens (private emails) This series of articles and the subsequent bibliography previously appeared in Mystery*File 47, February 2005, and is dedicated by Tom Jenkins and myself to the memory of Wyatt James, who died on January 12, 2006. His website A Guide to Classic Mystery Novels and Detective Stories will be maintained, as I understand it, and it is well worth your attention. There were few readers more passionate about The Golden Age of Detection than Wyatt, and he will most certainly be missed. (The annotated bibliography of Hubbard’s novels is slightly revised from its appearance on Wyatt’s website.) _____________________________________ YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. Copyright © 2005-2006 by Steve Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors. Return to the Main Page. |