|

IN THE FRAME, by Vince Keenan

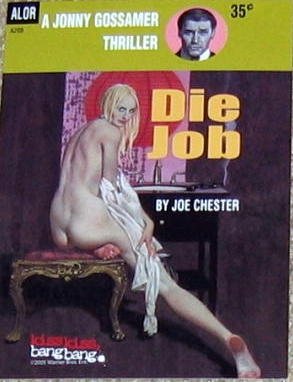

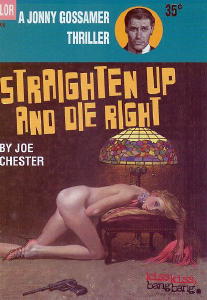

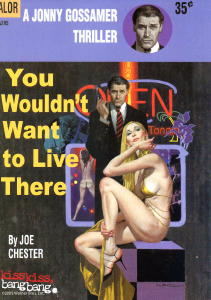

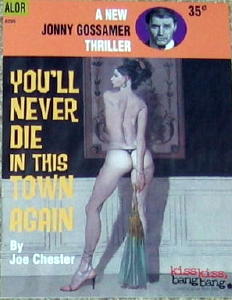

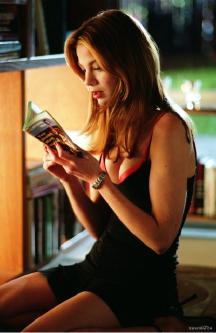

No movie I saw in 2005 provided a more pure entertainment rush than KISS KISS BANG BANG. I actually left the theater feeling giddy. The directorial debut of screenwriter Shane Black contains the outsized characters and smart-mouth dialogue of the action films with which he made his name in the late ’80s and early ’90s (LETHAL WEAPON, THE LAST BOY SCOUT, THE LONG KISS GOODNIGHT). But here his trademark irreverence is combined with an abiding reverence for the art of pulp storytelling. In fact, that’s the movie’s true subject. Too bad it never had a chance to find its audience. At its widest point of release, the film played on only 226 screens in North America. It grossed less than a third of its modest $15 million budget. Now that it’s on home video, its ample charms are waiting to be discovered. Robert Downey, Jr. plays Harry Lockhart, a two-bit New York thief mistaken for an actor. He’s sent to Los Angeles to audition for a role under the guidance of a tough homosexual P.I. known as Gay Perry (Val Kilmer). Harry quickly takes to the part; he’s soon investigating a case of his own involving a wannabe actress (Michelle Monaghan) whose aspirations are nearing their expiration date. Harry’s real gumshoe training comes from the novels about two-fisted shamus Jonny Gossamer. “Jonny spoke from the pages of cheap paperbacks” – bearing titles like Straighten Up And Die Right and You’ll Never Die in This Town Again, their lurid covers lovingly recreated – “and told of a promised land known as ‘the Coast’ and a magical city called Los Angeles.” Thanks to Jonny, Harry knows that the two cases he’s working on will prove to be connected, and that he’ll be tortured before solving them. But he’ll also learn that reality and fiction, especially in L.A., are often miles apart.

Black serves up a convoluted plot – one that does in fact make perfect sense – as an excuse to have fun with the mechanics of the mystery. He interrupts exposition to comment on it, at times stopping the film cold to call attention to the obvious planting of clues. This meta approach to narrative allows Black to send up storytelling clichés while reveling in how satisfying they can be when deployed effectively. His use of Raymond Chandler titles as chapter headings acknowledges his forebears, but also serves as a reminder: considering that this is the third of his films to feature a private eye as a major character, Black has done much to keep the archetype alive.  Michelle Monaghan is too young to play an actress on the verge of being washed up, but that doesn’t stop her from taking command of the screen in her first major role. (Mystery fans will soon see her as Angie Gennaro in the upcoming adaptation of the Dennis Lehane novel Gone, Baby, Gone.) Kilmer gets a chance to flex the comedy chops he demonstrated in his early films like TOP SECRET! and the underrated REAL GENIUS. But it’s Downey’s movie, and he has simply never been better. He delivers Black’s twisty, reflexive dialogue without seeming glib and handles the film’s quicksilver shifts in tone, from sardonic to heartbreaking, with preternatural grace. The actor’s reactions to violence, whether of the physical kind or the psychological variety inflicted by show business, give the movie a surprising emotional core. Both Downey and Black know the secret of boy’s own adventure stories: it’s that deep down, boys actually believe this stuff. The bare-bones DVD does feature a commentary track reuniting Black and his two leads that’s good for some laughs.  I had hoped that Black

would use the commentary to explain the film’s most intriguing credit:

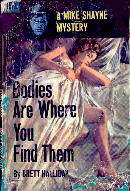

Based in part upon the novel Bodies Are Where You

Find Them, by Brett Halliday. An of-the-minute crime caper

drawing from a 1941 Mike Shayne mystery? I wanted to know

more. Black doesn’t get into the subject, so armed only with a

flashlight and a credit card I tracked down the Halliday book myself. I had hoped that Black

would use the commentary to explain the film’s most intriguing credit:

Based in part upon the novel Bodies Are Where You

Find Them, by Brett Halliday. An of-the-minute crime caper

drawing from a 1941 Mike Shayne mystery? I wanted to know

more. Black doesn’t get into the subject, so armed only with a

flashlight and a credit card I tracked down the Halliday book myself.It took me a few pages to adjust to the Halliday (aka Davis Dresser) style. Characters tend to snort angrily or sigh lugubriously. On page one Shayne “wiped beads of sweat from his corrugated brow.” Five pages later, “sweat stood on his corrugated brow.” Oops. Then the crackerjack plot kicks in. Shayne is on his way to New York with new bride Phyllis on the eve of Miami Beach’s mayoral election. The well-known private investigator has endorsed one candidate. When the daughter of the opposition turns up dead in Shayne’s office, the detective hides the body in hopes of unraveling the case before the votes are cast. KISS KISS BANG BANG borrows the skeleton of the plot from Halliday’s novel. The main debt owed to the book is a single clue that I won’t give away here, other than to say it’s the kind of detail that I can easily imagine making a vivid impression on a young Shane Black. Or Harry Lockhart. ***

The city of Seattle is

famous for its gray skies. Perfect film noir weather. But

it was a glorious June afternoon when the Seattle International Film

Festival presented two movies saved from oblivion by the Film Noir

Foundation. A few rays of sunshine weren’t about to change my

plans. I’ve seen sunshine before. The city of Seattle is

famous for its gray skies. Perfect film noir weather. But

it was a glorious June afternoon when the Seattle International Film

Festival presented two movies saved from oblivion by the Film Noir

Foundation. A few rays of sunshine weren’t about to change my

plans. I’ve seen sunshine before.The double bill was introduced by Eddie Muller, the Foundation’s founder and president as well as the author of several books about the genre (the definitive noir overview Dark City) and influenced by it (the novel The Distance). He began with a brief primer on the form, saying that noir breaks down into two camps. The James M. Cain school holds that individuals are responsible for whatever bad fate befalls them, while the Cornell Woolrich school believes that the universe is unfair and out to get everybody. Ultimately, all noir stories have one element in common: “People who know what they’re doing is wrong, but they do it anyway.” Muller outlined the Foundation’s mission to track down films that have fallen out of circulation and aid in their restoration. He brought the welcome news that only days earlier, the organization had located a new print of the 1949 Lizabeth Scott/Dan Duryea movie TOO LATE FOR TEARS, also known as KILLER BAIT. I have two copies of the film on DVD, one under each title and neither particularly sharp. But the script by TV legend Roy Huggins – creator of Maverick, The Fugitive and The Rockford Files – still crackles with energy. The film is ripe for rediscovery.  The day’s program began

with an example of noir’s “bad cop” subgenre, THE MAN WHO CHEATED

HIMSELF (1950). Its tortured production history explains

how it came to be lost; this only film produced by Jack M. Warner, son

of legendary studio head Jack L., was somehow released by Twentieth

Century Fox. The day’s program began

with an example of noir’s “bad cop” subgenre, THE MAN WHO CHEATED

HIMSELF (1950). Its tortured production history explains

how it came to be lost; this only film produced by Jack M. Warner, son

of legendary studio head Jack L., was somehow released by Twentieth

Century Fox.San Francisco police detective Lee J. Cobb falls hard for the woman Muller describes as “the least likely femme fatale ever,” Father Knows Best’s Jane Wyatt. “This new one’s good for me,” Cobb says of her. “She’s no good, but that’s the way it is.” When Wyatt kills her husband, Cobb covers up her role in the death – then investigates it alongside the squad’s newest member, his own brother (GUN CRAZY’s John Dall). The movie is no neglected masterpiece, but a solid entertainment directed by Felix Feist (THE DEVIL THUMBS A RIDE). It’s elevated in the closing moments by stunning location work in the Fort Point area years before Hitchcock made it famous in VERTIGO and a final scene between Cobb and Wyatt that communicates tremendous twisted longing in a single glance.  The second feature marked

a return to, in Muller’s words, “the good old days when you could

completely traumatize a nine-year-old boy.” THE WINDOW, a

retelling of “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” was the sleeper hit of 1949 and

earned young Bobby Driscoll a special miniature Oscar for his

performance. Despite that success, it hadn’t been widely seen in

decades. The Film Noir Foundation made the movie its inaugural

restoration project. The Foundation’s logo at the head of the new

print sparked a huge round of applause from a packed theater. Ted

Tetzlaff’s lean direction and villainous performances from Ruth Roman

and Paul Stewart – who at one point punches said nine-year-old in the

face – still hold up. (The Cornell Woolrich story that inspired

the movie was also the basis for 1984’s CLOAK & DAGGER.) The second feature marked

a return to, in Muller’s words, “the good old days when you could

completely traumatize a nine-year-old boy.” THE WINDOW, a

retelling of “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” was the sleeper hit of 1949 and

earned young Bobby Driscoll a special miniature Oscar for his

performance. Despite that success, it hadn’t been widely seen in

decades. The Film Noir Foundation made the movie its inaugural

restoration project. The Foundation’s logo at the head of the new

print sparked a huge round of applause from a packed theater. Ted

Tetzlaff’s lean direction and villainous performances from Ruth Roman

and Paul Stewart – who at one point punches said nine-year-old in the

face – still hold up. (The Cornell Woolrich story that inspired

the movie was also the basis for 1984’s CLOAK & DAGGER.)At the end of the film, Muller told the crowd that Bobby Driscoll died of a drug overdose in 1968, in a Greenwich Village tenement one block from where he’d filmed THE WINDOW as a child. He hated to send us out on such a grim note, he said, but when fate imitates noir you have to pay attention. As if on cue, the clouds had started rolling back in.  Note: Other installments of In the Frame can be found be going here. YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME.

Copyright © 2006 by

Steve

Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors.

Return

to

the Main Page.

|