|

Hard-boiled

Wit:

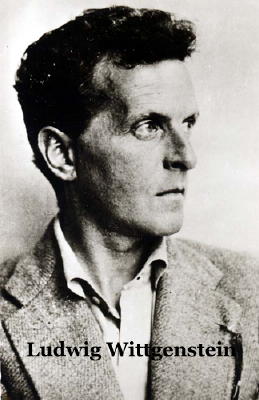

Ludwig Wittgenstein and Norbert Davis Josef Hoffmann

1. Introduction: Wittgenstein read Davis Rosro Cottage

Renvyle P.O. Co Galway Eire 4.6.48 Dear Norman, Thanks a lot for the detective mags. I had, before they arrived, been reading a detective story by Dorothy Sayers, and it was so bl... foul that it depressed me. Then when I opened one of your mags it was like getting out of a stuffy room into the fresh air. And, talking of detective fiction, I’d like you to make an enquiry for me when once you’ve got nothing better to do. A couple of years ago I read with great pleasure a detective story called Rendezvous With Fear by a man Norbert Davis. I enjoyed it so much that I gave it not only to Smythies but also to Moore to read and both shared my high opinion of it. For, though, as you know, I’ve read hundreds of stories that amused me and that I liked reading, I think I’ve only read two perhaps that I’d call good stuff, and Davis’s is one of them. Some weeks ago I found it again by a queer coincidence in a village in Ireland, it has appeared in an edition called ‘Cherry Tree books’, something like ‘Penguin’. Now I’d like you to ask at a bookshop if Norbert Davis has written other books, and what kind. (He’s an American.) It may sound crazy, but when I recently re-read the story I liked it again so much that I thought I’d really like to write to the author and thank him. If this is nuts don’t be surprised, for so am I. I shouldn’t be surprised if he had written quite a lot and only this one story were really good. Affectionately Ludwig  This letter is quoted in Norman Malcolm’s book Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir. Malcolm added the following footnote after Norbert Davis’s name: “As I recall, I was unable to obtain any information about this author.” The American philosopher Norman Malcolm was a student of Wittgenstein’s at Cambridge and later became a much esteemed correspondence partner and supplier of the latest detective pulps from the United States. It would appear, however, that Malcolm did not take his friend Ludwig’s desire to read more by Davis all that seriously. In 1948 he could have got hold of some short stories and books by Norbert Davis without much difficulty. After years of writing for the pulp magazines, Davis had managed in the 1940s to have his detective stories published in book form. Between 1943 and 1947 four such books appeared: The Mouse in the Mountain (1943; the paperback issues were called Rendezvous with Fear and Dead Little Rich Girl); Sally’s in the Alley (1943); Oh Murderer Mine (1946); Murder Picks the Jury (1947). No more books followed. In 1949, at the age of 40, Norbert Davis took his life. The fact that Wittgenstein’s attempt to get in touch with Davis failed is tragic somehow. If anyone could have helped Norbert Davis then, in my view, it was Ludwig Wittgenstein. He was an influential philosopher who managed throughout his entire life to rope his wealthy friends and relatives into supporting hapless individuals, in particular writers and artists. Wittgenstein’s enthusiasm for Norbert Davis’s first novel is understandable. This particular novel betrays, as do other texts by Davis, a similar mode of thinking and writing, a kind of elective affinity to Wittgenstein’s own work. What is more, in his earlier years Wittgenstein had been repeatedly haunted by thoughts of suicide. Three of his brothers had ended their lives by suicide. In fact, suicide was part and parcel of the whole milieu in which he spent his earlier life in Austria . In his biography, Ray Monk refers to that milieu as a “Laboratory for Self-destruction.” Today, a half a century later, it is impossible to make up for Malcolm’s neglect to inquire about Davis and so historically cancel out that non-encounter between him and Wittgenstein. It is possible, however, to address the question of why Wittgenstein estimated Norbert Davis’s novel so highly that he felt a need to thank him personally for it. 2. Wittgenstein as a culture lover and crime fiction reader In 1948, three years before his death, Wittgenstein was a famous philosopher who was supported by people like Bertrand Russell, George Moore, John Maynard Keynes, and not least, by his siblings in Austria. He came from one of the richest and culturally most influential families in Vienna at the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Brahms, Mahler, Klimt, and Grillparzer were just some of the guests to visit the Wittgenstein home. Ludwig’s older brother Paul became a famous pianist. It was for him that Ravel composed his “Piano Concerto in D Major for Left Hand”; Paul Wittgenstein had lost his right arm in the First World War. As a child already, Ludwig Wittgenstein had got to know and love the literature and music of the German speaking region, maintaining throughout his whole life a particular leaning towards classical music. As for literature, he was especially taken by the works of Goethe, Mörike, Keller, Hebel, Lenau, and Nestroy, though he also liked Tolstoy, Dostoievski, Sterne, Lewis Carrol, Dickens, and the young Joyce. In 1914, through the editor of the Austrian magazine Der Brenner, Wittgenstein had a donation of 100,000 Kronen (about €100,000 today) distributed among “penniless Austrian artists,” including, among others, Rilke, Trakl, Lasker-Schüler, Kokoschka, Haecker, and Däubler.  Between 1926 and 1928, Wittgenstein, together with Paul Engelmann, a disciple of the modernist architect Adolf Loos, supervised the construction of the so-called Wittgenstein Palais on Kundmanngasse in Vienna for his sister Gretl. Both the exterior and the interior of the house were designed in a style similar to that of Loos and the Bauhaus. Once his tasks were completed, Wittgenstein liked to go and see westerns, above all Tom Mix films, together with Engelmann. Later, in Cambridge, he developed an enthusiasm for American review films which he preferred to watch from the front row of the cinema. It cannot be established conclusively when exactly Wittgenstein began reading crime fiction, though it had definitely become a fixed component of his reading material after his return to Cambridge in 1929. His preference was for Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, a monthly pulp magazine which he read, more or less regularly, up until his death. Wittgenstein liked this magazine so much that he quoted it in the last lecture he gave as a fellow of Trinity College. That is not all. In his letters to Norman Malcolm he mentions several times how important the magazine was for him, much more important than the leading philosophy magazine of the time, Mind. In the context of paper rationing in England he wrote to Malcolm on 8.9.1945: “Thanks a lot for the mags. ... The one way in which the ending of Lend-Lease really hits me is by producing a shortage of detective mags in this country. I can only hope Lord Keynes will make this quite clear in Washington. For I say: if the U.S.A. won’t give us detective mags we can’t give them philosophy ...” A letter dated 15.3.1948 contains the following lines: “Your mags are wonderful. How people can read Mind if they could read Street & Smith beats me. If philosophy has anything to do with wisdom there’s certainly not a grain of that in Mind, and quite often a grain in the detective stories.” Mind came off even more negatively in another comparison made in his letter of 30.10.1945: “If I read your mags I often wonder how anyone can read Mind with all its impotence and bankruptcy when they could read Street & Smith mags. Well, everyone to his taste.” Wittgenstein’s preference in crime fiction was not exclusively for “hard-boiled detective stories,” as Ray Monk’s biography would have us believe. M. O’C. Drury, a close friend of Wittgenstein’s, recalled a conversation he once had about crime fiction with Wittgenstein in 1936 during which Wittgenstein praised Agatha Christie, claiming that it required a specifically English talent to be able to write such books. For Wittgenstein, Christie’s crime stories were a pure delight. Not only were the plots cleverly worked out, the characters too, were so well portrayed that they seemed like real people. On once being recommended to read Chesterton’s Father Brown stories, Wittgenstein turned up his nose: “Oh no, I couldn’t stand the idea of a Roman Catholic priest playing the part of a detective. I don’t want that.” In light of that conversation with Drury in the mid-1930s, it can be safely assumed that Wittgenstein’s taste complied with that of his time, and that he therefore partook of all the developments in crime fiction. His liking for the more modern literary style of the hard-boiled detective stories probably developed when they had made their way into almost all the crime story magazines, including Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine – on the model of the Black Mask. As Ray Monk points out, in the 1930s and 40s, Detective Story Magazine carried works by Black Mask authors such as Raymond Chandler, Carroll John Daly, Erle Stanley Gardner, Cornell Woolrich and Norbert Davis. Wittgenstein, however, always speaks of detective stories, which would lead one to presume that the other sub-genres in crime fiction, such as gangster or action stories and psycho-thrillers, did not appeal to him as much. Most of the detective stories of the hard-boiled school had basic elements in common with the classical whodunits, so that the change in the reading public’s habits could take place gradually. 3. The characteristic features of Norbert Davis’ detective stories Norbert Davis was no realist. He was not interested in depicting reality in the raw, nor in presenting characters, scenes and dialogues that seemed as if they were borrowed from harsh everyday life. What characterises Davis as a hard-boiled writer is the cutting and curt linguistic and narrative style he chose in order to portray a thoroughly corrupt and violent world. Often the vocabulary is bold and simple, the short, precise sentences stylistically well honed.  Occasionally he even uses

internal rhyme and

alliteration: “A Lady gets a Lift,” “Target for Teresa,” “A Break for a

Bum,” “Give the Devil his Due,” and “Latin in Art” (from The Adventures of Max

Latin). Davis’s dialogues ooze sarcasm. Pathos,

sentimentality or naivety‚ of any kind are averse to his hardened

protagonists. The best example of this is his private detective

Doan. In one scene in The Mouse in the

Mountain the bandit Garcia lies dead on the ground after an

exchange of shots. A Mexican officer examines him: Occasionally he even uses

internal rhyme and

alliteration: “A Lady gets a Lift,” “Target for Teresa,” “A Break for a

Bum,” “Give the Devil his Due,” and “Latin in Art” (from The Adventures of Max

Latin). Davis’s dialogues ooze sarcasm. Pathos,

sentimentality or naivety‚ of any kind are averse to his hardened

protagonists. The best example of this is his private detective

Doan. In one scene in The Mouse in the

Mountain the bandit Garcia lies dead on the ground after an

exchange of shots. A Mexican officer examines him: “Dead,” said the tall man. “That is

unfortunate.”

“For him,” Doan agreed. Davis’s plots, characters, and basic character constellations betray a marked proximity to the classical whodunits. Figures such as Max Latin or Doan represent a blend of the invariably unequalled master detective and the hard drinking rough-shod private eye. Also borrowed from the tried and tested range of traditional forms are plot elements and scenes such as the configuration of potential perpetrators and victims in a ‘closed society’ (for example, in “Holocaust House”), or the concluding summary by the detective who solves the case before an astonished audience. Davis’s combination of elements from different narrative styles succeeds because he ironically stretches the forms of both kinds of detective story to breaking point and seasons both plot and dialogue with a touch of humour. The humour of his verbal and situation comedy is often achieved by leaving out elements in customary forms of communication, and especially by taking what people say (but do not necessarily mean) obstinately literally – like a reductio ad absurdum. As a result, Davis’s humour takes on anarchic and bizarre features, similar to those of Marx Brothers films. Here is a sample from “Give the Devil his Due”: “... You are Max Latin, and you call

yourself a private inquiry agent, and you are the undercover owner of

this restaurant.”

“Well, how do I do,” said Latin. “I’m glad to know me.” And another from The Mouse in the Mountain: “Friend,” said Henshaw, “... I’m in the

plumbing business — ‘Better Bathrooms for a Better America.’ What’s

your line?”

“Crime,” Doan told him. “You mean you’re a public enemy?” Henshaw asked, interested. “There have been rumors to that effect,” Doan said. “But I claim I’m a private detective.” This clever, laconic, and sarcastic narrative style is surely the main reason why Davis’s novel appealed to Wittgenstein so much. Incidentally, a Davis comment such as “... ‘Latin,’ said Latin” is quite in keeping with Wittgenstein’s “Mr. Scot is no Scot” (in his Philosophical Investigations, part ii). 4. The proximity of Wittgenstein’s mode of thinking, writing, and life to that of the ‘hard-boiled school’ As in both the traditional and the more modern detective stories, the main concern in Wittgenstein’s work is with transparency, with arriving at certainty about facts, at a correct view and elucidation of the real connections by means of eliminating deceptions and apparent constructs. Wittgenstein’s wish was to expose pretence, hypocrisy, puffiness, slovenliness and obscuration, which are as widespread in the realms of philosophy and science as they are in the avaricious world of commerce. He compared many contemporary philosophers to cheats and businessmen who capitalised on poor districts, and saw it as his task to put a stop to such activities by his colleagues. Given that Wittgenstein’s philosophical work, like the typical detective story, dealt with the exposure of deception, he naturally approached facts in a way that was reminiscent of a detective’s approach to solving problems. §129 of his Philosophical Investigations reads like a summary of Poe’s “Purloined Letter,” a story in which a stolen letter remains concealed from the eyes of the investigators simply by being placed openly on a card-rack, visible to all at any time. Wittgenstein writes: “The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity. (One is unable to notice something — because it is always before one’s eyes.)” Individual sentences in §99 of his Philosophical Investigations may even contain an allusion to a typical element of crime fiction, namely, ‘the locked room mystery’: “... if I say >I have locked the man up fast in the room – there is only one door left open< – then I simply haven’t locked him in at all; his being locked in is a sham. ... An enclosure with a hole in it is as good as none.” Are the following lines from §293 of Philosophical Investigations not almost a parodistic portrayal of the typical scene in which the master detective recapitulates the events of the crime before a confounded audience, eliminating a ‘red herring’ that had misled the investigations. “Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a ‘beetle.’ No one can look into anyone else’s box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle. – Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing. – But suppose the word ‘beetle’ had a use in these people’s language? – If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty. – No, one can ‘divide through’ by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is.”  §115 points in a

similar direction: “A picture

held us captive.” Wittgenstein devoted his repeated attention to

the influence of our cultural surroundings on the way we view

things. Davis too, refers to such influences again and again, in

a particularly sarcastic manner at the beginning of chapter 3 of Sally’s in the Alley: §115 points in a

similar direction: “A picture

held us captive.” Wittgenstein devoted his repeated attention to

the influence of our cultural surroundings on the way we view

things. Davis too, refers to such influences again and again, in

a particularly sarcastic manner at the beginning of chapter 3 of Sally’s in the Alley:

The Mojave Desert at sunset

looks remarkably like a painting of a sunset on the Mojave Desert

which, when you come to think of it, is really quite surprising. Except

that the real article doesn’t show such good color sense as the average

painting does. Yellows and purples and reds and various other violent

sub-units of the spectrum are splashed all over the sky, in a

monumental exhibition of bad taste. They keep moving and blurring and

changing around, like the color movies they show in insane asylums to

keep the idiots quiet.

In some of Wittgenstein’s writings on the task of philosophy, all that is necessary is to substitute a few words – those marked in bold type in the following – in order to illustrate their affinity to crime fiction: “A detective’s problem has the form: ‘I don’t know my

way about’ ” (§123 PI).

“The work of the detective consists in assembling reminders for a particular purpose.” (§127 PI) “What is your aim working as a detective? – To shew the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.” (§309 PI) In his remarks on this statement, Wittgenstein expert Joachim Schulte further underlines its similarity, in form and content, to the attitude of a private detective à la Philip Marlowe to a female client, as it were, the threatened ‘fly.’ In Schulte’s eyes, the fact that the fly has fallen into the trap means it is in considerable danger, not just because of a total lack of orientation, but because it has become so completely entangled that it cannot free itself. The man who comes to the aid of such an ‘imprisoned’ client is indeed a veritable saviour in her hour of need. Not only did Wittgenstein distrust abstruse, mysterious sounding waffle in philosophy, he also regarded the equation of mathematical logic and science as a misconception. In this sense Ray Monk may be correct in assuming that Wittgenstein was better able to identify with the approach of the hardened American private detective than with the methods of a Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot. And just as the new style down-to-earth private eye was opposed to the old style detective and his apparently logical deductions, Wittgenstein too was keen to distance himself from the representatives of a mathematization of philosophy and science. For him, the fundamentals of mathematical logic were based on mere agreements, that is to say, human inventions, and were thus totally different from the laws of nature. When writing his Tractatus, Wittgenstein had already come to the conclusion that science and philosophy were far removed from those things in life which are of greatest importance to the individual: “6.52 We feel that even when all possible scientific questions have been answered, the problems of life remain completely untouched.” Norbert Davis seems to have shared this viewpoint, as illustrated above all in the last chapter of Oh Murderer Mine. At one stage in the narrative, Doan’s dog Carstairs, a Great Dane, chases the dim-witted arrest-happy campus policeman Humphrey into the swimming pool, completely ignoring Doan’s admonitions. In turn, Doan is also ignored by the two university lecturers Eric and Melissa, who are locked in passionate embrace.

Carstairs ignored him. Carstairs was contemplating the frothy,

turgid water in the pool with the remotely sadistic indifference of a

scientist studying a pinned-down bug.

And Eric and Melissa ignored him too. For the moment they were too occupied with each other to have any interest in external affairs. Melissa’s arms were about Eric’s neck and he was holding her so closely that no bio-chemist or meteorologist or physicist or psychologist or any other scientist could have presented a logical explanation of how it was that she could breathe.”  The Tractatus puts it more succinctly, under 6.43: “The world of the happy man is a different one from that of the unhappy man.” Like the above mentioned fly bottle metaphor, Wittgenstein’s remarks on the work of the philosopher betray a disillusioned and bitter, if tenacious and dogged attitude to his profession and one that is sometimes redolent of, among other things, the particular professional attitude and street wisdom of the private detective of the hard-boiled school. As the founder of so-called “ordinary language philosophy,” Wittgenstein was more likely to be sympathetic towards detectives who spoke the language of ordinary people and grappled, despite the hard knocks with, everyday problems and real opponents, than towards the classical detectives who caught criminals on the basis of their ingenious gift of association, or even their clairvoyant capacities. Wittgenstein’s preference for the working methods of hard-boiled detectives can also be easily demonstrated by the use of slightly modified quotations from his Philosophical Investigations: In the detective’s work we do not draw conclusions.

(§599)

Here it is difficult as it were to keep our heads up, – to see that we must stick to the subjects of our every-day thinking, and not go astray and imagine that we have to reconstruct extreme subtleties, which in turn we are after all quite unable to reconstruct with the means at our disposal. We feel as we had to repair a torn spider’s web with our fingers. (§106) We have got on to slippery ice where there is no friction and ... we are unable to walk. We want to walk: so we need friction. Back to the rough ground! (§107) I can look for him when he is not there, but not hang him when he is not there. (§462) The results of a detective’s work are the uncovering of one or another piece of plain nonsense and of bumps that he has got by running its head up against the limits prescribed. These bumps make us see the value of the discovery. (§119) Could such terms not also be used to describe the ‘philosophy’ of the ‘tough private eye’? In “You Can Die Anyday,” Max Latin puts it somewhat more bluntly and briefly: “ ... so I went right ahead anyway. I couldn’t wait to investigate. I had to poke my neck out.” It is quite possible that some of Wittgenstein’s remarks on the theme of the rules of the game, on ‘being guided,’ and on reading might well have been inspired by the narrative technique of crime fiction, by that subtle tactic of keeping the reader on tenterhooks until the finale. For example, in §652 of Philosophical Investigations we read: >He measured him with a hostile glance

and said ....< The reader of the narrative understands this;

he has no doubt in his mind. ... But it is possible that the

hostile glance and the words later prove to have been pretence, or that

the reader is kept in doubt whether they are so or not, and so that he

really does guess at a possible interpretation. – But then the main

thing he guesses at is a context. He says to himself for example:

The two men who are here so hostile to one another are in reality

friends, etc. etc.

A central theme in Wittgenstein’s late writings is the question of what rules are, how they can be recognised, drawn up, and obeyed. This brings us to another reason why he favoured American detective stories such as those by Davis. It is a well known fact that private detectives like Max Latin or Doan neither adhere to the rules of logical deduction nor to those of law or social conventions. Instead, they think and act as the situation demands, breaking rules, changing them, or merely pretending to comply with them. Wittgenstein’s deliberations on the theme of rules had their roots in internal developments within philosophy. Yet they also have to be seen against the backdrop of the fundamental change that took place in people’s consciousness in the face of the social turmoil of the first half of the twentieth century, which had invalidated rules regarded as self-evident until then. One feature of the experience of the generations who lived through the First and Second World Wars and the critical inter-war period was insecurity, lost certainty, as regards which values and rules could still aspire to validity. Such an experience gives rise to a need for orientation, certainty, and security, for reliable rules for individual and social life which were worth keeping and defending unyieldingly against attack. Yet in view of the myriad opinions, proposals, declarations and world views circulating and competing in the public arena in free societies, it was difficult even for intelligent people to establish binding rules and certainties. This intellectual state is reflected not only in the philosophy of the time, but also in literature and films, and in particular in that narrative domain encompassed by the term ‘noir.’ It was common to consider the writers of those ‘black’ stories as having an intellectual affinity with the French existentialists, though this is not always the case. Some ‘noir’ writers have closer ties with other philosophies, for example that of Karl Marx, Charles Peirce, or Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein’s view of his time was presumably more gloomy – and elitist – than that of many ‘noir’ writers, as is illustrated, for example, at one point in the foreword to his Philosophical Investigations: “It is not impossible that it should fall to the lot of this work, in its poverty and in the darkness of this time, to bring light into one brain or another – but, of course, it is not likely.” Another possible point of identification for Wittgenstein with hard-boiled crime fiction could well have been the particular role that the new private detective assumed in society. He was a lone fighter caught between the fronts of the rich upper class and the desolate world of poverty, between city administration and the police force on the one hand, and the underworld on the other. Wittgenstein too saw himself in the role of the lonesome warrior, pitting his energies against both the bourgeois academic life style and the narrow-mindedness and ‘meanness’ of normal people – against whom he had railed frequently, especially in his younger years. Like the modern private detective, Wittgenstein seemed to move in various social ‘camps’ or milieus without feeling at home in any of them. Wittgenstein’s attitude to life, more precisely, the type of masculinity and the ideals of truthfulness and honour he admired, betray common features with those of Dashiell Hammett and other writers of the hard-boiled school. Like Hammett, it was not enough for Wittgenstein to merely prove his worth at that ‘battlefield in life’ that seemed to have been allocated to him, namely, his desk. Both men found it unbearable not to be active like other men at the real front, where what was at stake was life and death, and where they could demonstrate their bravery. In wartime they could direct their aggressive impulses against real enemies, reaping recognition while at the same time keeping under control, or covering up, their self-destructive potential. Although neither Wittgenstein nor Hammett enjoyed good health, they both managed to have themselves recruited for wartime service. During the First World War Wittgenstein refused military positions that would have prevented him from doing gun battle with enemy soldiers. As a lone observer at the front, he was persistent in battle, intervened in troop action directly where necessary, and was awarded a medal for bravery. During the Second World War he gave up his teaching post in Cambridge to work at Guy’s Hospital, thus making his contribution to the war against the Nazis. He justified his decision as follows: “I feel I will die slowly if I stay there. I would rather take a chance of dying quickly.” Hammett had contracted tuberculosis during the First World War and therefore could not fight at the front, however, he only gave up his job as a Pinkerton detective when ill-health finally forced him to. Yet despite his advanced years and unfit state, he succeeded by all sorts of tricks in being despatched to the front as a soldier during the Second World War. Another common element in the attitudes of Hammett and Wittgenstein to life in general was that they both despised the easy life and were not interested in money. For a time both of them had strong leanings towards communism. Wittgenstein travelled to Russia in 1935 with the intention of working there but returned to England disappointed. During the McCarthy era, Hammett chose to go to prison with his Marxist friends out of loyalty. After the First World War, Wittgenstein chose to stay on longer in a prisoner-of-war camp out of attachment to his comrades and refused an early discharge. Like Chandler or Davis, Wittgenstein and Hammett also had no illusions about the fact that people and things could be easily bought. Sally’s in the Alley contains some rather vicious statements to this effect. On one occasion, when Doan gets into a tussle with Susan Sally, a good-looking Hollywood actress, her worried agent calls out: “Hit her in the stomach!”

“What?” said Doan, startled. The shadow jiggled both fists in an agony of apprehension. “Not in the face! Don’t hit her face! Thirty-five hundred dollars a week!” Towards the end of the story, Doan and Harriet, a patriotic but rather naive companion, engage in the following conversation with the Nazi MacAdoo: “Goering is going to be hung after we win

the war," Harriet told him.

MacAdoo looked at her. “Don’t be silly. The Kaiser didn’t have much more than a hundred million dollars, and nobody hung him. Goering is worth two or three billion by this time, and besides that he has heavy influence in England and the United States.” “How do you know?” Doan asked. “Read the papers. Who do you think is paying for all this bilge about Goering being a harmless, jolly fat man with a love for medals and a heart of gold? Stuff like that isn’t printed for free. Particularly not after the guy involved has murdered a half million civilians with his air force. I shouldn’t wonder but what he’ll wind up as president of the Reich under a, pause for laughter, democratic government.” In view of their socially privileged status, Wittgenstein’s and Hammett’s attitudes to life and work may seem ambivalent, which could also be one of the reasons for their unease, the dissatisfaction, and perhaps even their inability to produce one masterpiece after another, as other writers were obviously able to do. From the publication of his novel The Thin Man in 1934 to his death in 1961, Hammett was never again in a position to complete another work despite desperate attempts. In the foreword to his Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein wrote resignedly that he would have liked to produce a good book but that there was no time left to improve it. “After several unsuccessful attempts to weld my results together into such a whole, I realized that I should never succeed. The best that I could write would never be more than philosophical remarks ...” That reminds me of Chandler’s lament in a letter to Sandoe: “I am continually finding myself with scenes that I won’t discard and that don’t want to fit in. ... The mere idea of being committed in advance to a certain pattern appalls me.” A glance at Davis’s publications reveals that he drafted a considerable number of characters and wrote innumerable ‘novelettes and short stories’ but produced only very few novels, and they are extremely short. He too, was obviously lacking the ability to produce an extensive, well conceived oeuvre. However, as very little is known about the conditions under which Davis lived and worked, all I can do is subscribe to John D. MacDonald’s evaluation of him as a typical pulp writer: “I never met Norbert Davis, but I have no reason to suspect that he was any less eccentric, or less anxious, in that penny-a-word environment than any of the rest of us.”  5.

Wittgenstein – a philosopher with a “hard-boiled” style? 5.

Wittgenstein – a philosopher with a “hard-boiled” style?In many ways, Wittgenstein’s style of writing betrays an affinity to the prose of the Black Mask school, especially to that of Norbert Davis. Wittgenstein had an abhorrence of what he called “waffle”, and was almost obsessed with a brief, precise, logical form of expression. He tormented people around him by constantly correcting mistakes in their syntax. Both in his private texts and conversations, and in his dairy entries, letters, and philosophical writings, he tended towards coarse, hard-boiled expressions and sarcastic humour. He had a preference for laconic turns of phrase intended to illustrate a thought ‘in a flash.’ The term ‘wise crack’ might be used to put his style of writing philosophy in an appropriate nutshell, were it not already reserved for the sharp-witted dialogues of Philip Marlowe and his colleagues. Wittgenstein’s translators (from German into English and vice versa) were apparently so painfully embarrassed by his provocative sarcasm that they occasionally went to great trouble to mellow the tone of the original text, transposing it into a more scholarly, bourgeois key, as I shall show later. One reason for this procedure may have been that they did not wish to expose Wittgenstein’s work to the danger of being considered lacking in seriousness and thus not being received appropriately. As one of the editors of the works published posthumously, Georg Henrik von Wright, emphasises, Wittgenstein had acquired the reputation of being a cultural ignoramus – not least because of his Spartan way of life and his dislike for the Cambridge milieu. Furthermore, many contemporaries found him impolite, blunt, barefaced, even cruel. In view of such reproaches and prejudices, it may have seemed appropriate to the translators to soften or defuse those of Wittgenstein’s expressions that might have confirmed such prejudices against his person and his work. Thus for a long time, biographical works made no mention of, or at least ignored, the fact that in his later years he was a passionate reader of crime stories and even spoke about them in his lectures. Let us now turn to some original texts by Wittgenstein that document his ‘hard-boiled’ style. On 9.7.1916, that is to say, while serving in the war, Wittgenstein made the following entry in his diary in secret writing: “Don’t get worked up about people. People are black scoundrels.” His diary entry of 19.8.1916 repeats the sentence: “Surrounded by meanness.” In a letter to Paul Engelmann dated 16.1.1918 he writes: “I am clear about one thing: I am far too bad to be able to theorize about myself; in fact I shall either remain a swine or else I shall improve, and that’s that! Only let’s cut out the transcendental twaddle when the whole thing is as plain as a sock on the jaw.” In a later letter: “Perhaps I should first have to be shattered completely by a blow from outside, before new life could enter this corpse.” On postcards sent to Gilbert Pattison, Wittgenstein resorted to particularly drastic phrases: Of Chamberlain’s diplomacy in Munich he writes on one card: "In case you want an Emetic, there it is.” He concludes another postcard greeting with the words: “... I am, old God, yours in bloodyness, Ludwig”.  Both Wittgenstein’s

private and philosophical notes

contain phrases that could have come from a crime story: Both Wittgenstein’s

private and philosophical notes

contain phrases that could have come from a crime story: “I see someone pointing a gun and say

>I expect a report<. The shot is fired.” (PI §442)

“I watch a slow match burning, in high excitement follow the progress of the burning and its approach to the explosive.” (PI §576) In December 1929 Wittgenstein reported a dream about a man called Vertsag: “He opens fire with a machine-gun at a cyclist behind him who writhes with pain and is mercilessly gunned to the ground with several shots. Vertsag has driven past, and now comes a young, poor-looking girl on a cycle and she too is shot at by Vertsag as he drives on. And these shots, when they hit her breast make a bubbling sound like an almost empty kettle over a flame.” The hard-boiled crime stories of the 1940s frequently contain accounts of torture scenes and pain endurance rites. A favourite plot element is the state of complete uncertainty in which the detective or the victim of the crime find themselves. In his way of examining philosophical problems, Wittgenstein succeeded in blending these two elements: ... several people standing in a ring, and

me among them. One of us, sometimes this one, sometimes that, is

connected to the poles of an electrical machine without our being able

to see this. I observe the faces of the others and try to see

which of us has just been electrified. – Then I say: “Now I know who it

is; for it’s myself.”

(PI §

409)

The following German sentence “Daß mich das Feuer brennen wird, wenn ich die Hand hineinstecke: das ist Sicherheit.” is rendered as follows in the English version: “I shall get burnt if I put my hand in the fire: that is certainty.” (PI §474) Were the German to have been translated literally, it would read: “That fire will burn me if I put my hand into it: that is certainty.” Wittgenstein’s German text makes a particularly sharp point due to the fact that the German word “Sicherheit” means both certainty and security. The second connotation is absent from the English word “certainty.” The syntactical alteration also diminishes the harshness of the expression. Almost nothing is sacred to the hard-boiled private detectives. Their impertinence and unscrupulousness overwhelms not only their opponents and their competitors, but even their clients. In Davis’s short stories, the detective figures play a particularly cunning game with the people they encounter. The following statement by Wittgenstein could also have been made by a trickster such as Detective Max Latin: “Someone says to me: >Shew the children a game.< I teach them gaming with dice, and the other says >I didn’t mean that sort of game.<” (PI, note added to §70) The same unsentimental, self-mocking humour with regard to his own profession can be found, expressed in equally mordant tones, in Wittgenstein’s statements on the philosopher: “I am sitting with a philosopher in the garden; he says again and again >I know that that’s a tree<, pointing to a tree that is near us. Someone else arrives and hears this, and I tell them: >This fellow isn’t insane. We are only doing philosophy.<” (On Certainty §467) The relationship between life and death has always been a fundamental preoccupation in philosophy, as in crime fiction. Davis’s novel The Mouse in the Mountain could well have been inspired Wittgenstein to the following statement: “And so, too, a corpse seems to us quite inaccessible to pain. – Our attitude to what is alive and to what is dead, is not the same. All our reactions are different.” (PI §284) Davis’s story contains a piece of dialogue that humorously illustrates Wittgenstein’s claim. After private detective Doan shoots gangster Bautiste Bonofile in a struggle, Doan’s companion Janet asks, worried: “Is he – hurt?” “Not a bit,” said Doan. “He’s just dead.” A few pages later, Doan puts forward a variation on logical problem contained in the proposition, “A Cretan says, ‘All Cretans are liars’ ”: “Yes, I lied to him.”

“Well, aren’t you ashamed ? You involved me, too.” “You shouldn’t have believed me,” Doan said... “Why not ?” Janet demanded indignantly. “Because I’m a detective,” Doan said. “Detectives never tell the truth if they can help it. They lie all the time. It’s just business.” “Not all detectives!” Doan nodded, seriously now. “Yes. Every detective ever born, and every one who ever will be. Honest.” ****

This article first

appeared in CADS #44, October

2003. Copyright © 2003,

2006 by Josef

Hoffmann.

CADS

is

a British mystery fanzine published irregularly by Geoff Bradley, 9

Vicarage Hill, South

Benfleet, Essex SS7 1PA, England. For a sample issue, send

£5.50 (UK) or $11 (US/Canada, airmail). Please make checks

payable to G. H. Bradley.

It should also be noted that Josef has a further article “PI Wittgenstein and Language-games from Detective Stories” in CADS 48, October 2005. PHOTO GALLERY

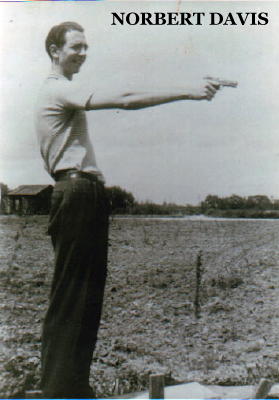

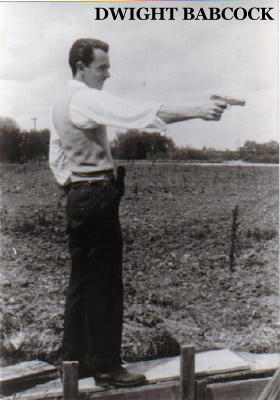

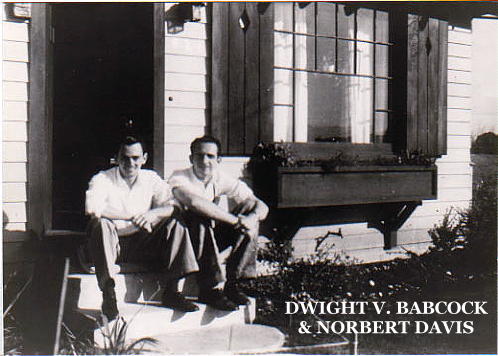

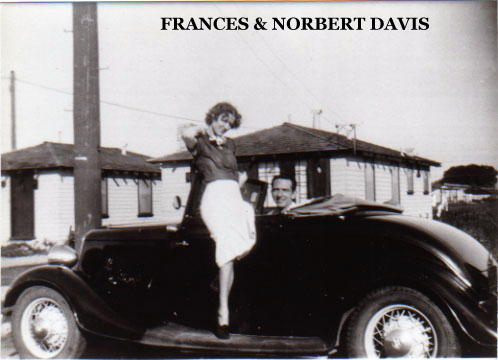

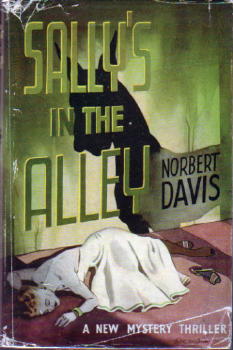

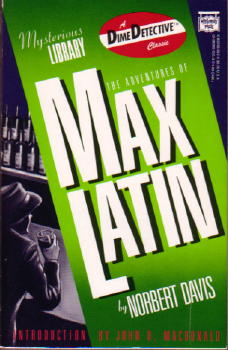

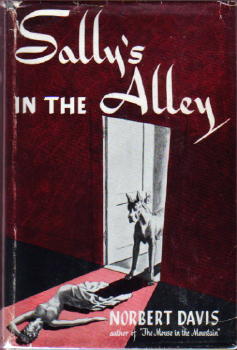

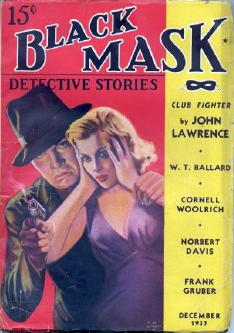

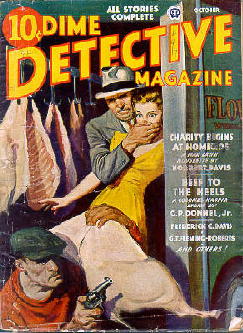

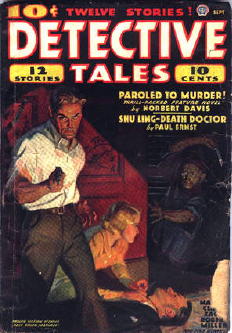

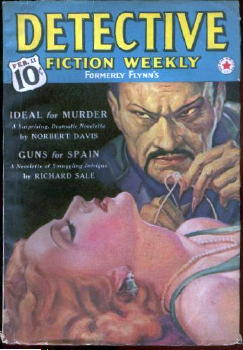

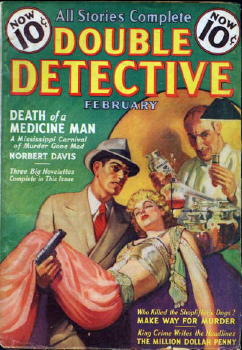

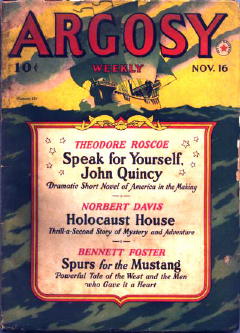

The photos below were obtained several years ago by Bill Pronzini from Ruth Babcock, widow of Norbert Davis’s fellow pulp writer, Dwight V. Babcock. With the assistance of John Apostolou, who has done extensive research into the lives of both Davis and Babcock, we no longer believe that all five photos came from the same visit by the Davises at the Babcocks’ home. Norbert Davis made a trip in 1936 to a farm owned by Ruth Babcock’s family in Modesto, California. While there, he and Dwight did some target shooting. Photos were taken and some prints sent to Joseph T. Shaw in April 1936. Three of the pictures – Norbert shooting, Dwight shooting, the two of them sitting – were taken during that visit. The house in the picture of the car appears to be the same house in the photo with Babcock and Davis sitting on the front steps. If this is so, it would suggest that the woman standing on the running board of the car is Frances, Norbert Davis’s first wife. (If anyone can identify what brand of automobile this sporty convertible might be, we’d like to know that too.) The remaining picture of three seated individuals was shot, we now believe, at a different location several years later. Norbert has aged considerably, and the house is clearly not the same one as in the other two shots. John suggests that the picture may have been taken in 1948 or early 1949. The woman seated in the middle is Nancy Davis, Norbert’s second wife. She would have been about 27 years old. (Apparently target shooting was a common pastime for the two writers. Note that Davis is holding a gun in that later photo as well.) Nancy Kirkwood Crane Davis was also the daughter of mystery writer Frances Crane, a fact uncovered by Tom and Enid Schantz while researching Davis’s life for their introduction to the Rue Morgue Press editions of his books. If you’re interested in learning more about Norbert Davis and his life, you’re strongly urged to read it. It’s excellent and definitely worth your while.

NORBERT

DAVIS

(1909-1949): A

BIBLIOGRAPHY - by Steve Lewis, Bill Pronzini & Victor A. Berch NOVELS & COLLECTIONS -

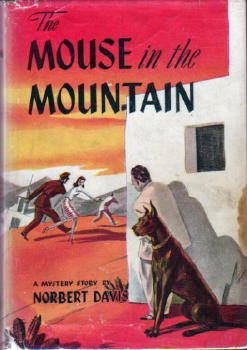

The Mouse In The

Mountain. Morrow, hc, 1943.

[Doan and Carstairs.]

Sally’s In The

Alley. Morrow, hc, 1943. [Doan

and Carstairs.]

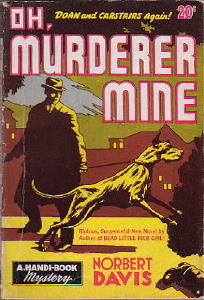

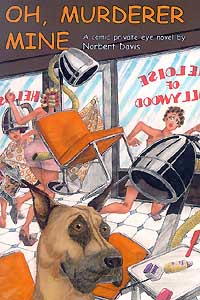

Oh, Murderer Mine.

Handi-Books #54, pb original, 1946. [Doan and

Carstairs.]

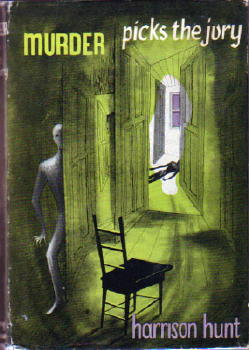

Murder Picks The

Jury, as by Harrison Hunt (joint pseudonym with W.

T. Ballard). Mystery House, hc, 1947. The Adventures of Max Latin.

Mysterious Press, trade pb, 1988. Introduction by John D.

MacDonald. SHORT FICTION - Stories in BLACK MASK “Reform Racket” June 1932. “Kansas City Flash” March 1933. ● Reprinted in Murder, Plain & Fanciful, James Sandoe, editor. (Sheridan House, hc, 1948)  ● Reprinted in The Hard-Boiled Detective, Herbert Ruhm, editor. (Vintage Books 72156, pb, 1977) “Red Goose” February 1934. ● Reprinted in The Hard-Boiled Omnibus: Early Stories from Black Mask, Joseph T. Shaw, editor. (Simon & Schuster, hc, 1946; Pocket #852, pb, 1952) ● Reprinted in The Mammoth Book of Pulp Action, Maxim Jakubowski, editor. (Constable & Robinson, UK, trade pb, 2001; Carroll & Graf, trade pb, 2001) ● The basis (we presume) for the episode broadcast “The Blue Panther” on the TV series Suspense, October 15, 1952. [When re-registered for copyright, the origin was listed as “The Blue Goose,” by Norbert Davis. This has to be an error for “Red Goose.”] “The Price of a Dime.” April 1934. “Hit and Run” April 1935. “Medicine for Murder” October 1937. “Murder in Two Parts” December 1937. ● Reprinted in American Pulp, Ed Gorman, Bill Pronzini, & Martin H. Greenberg, editors. (Carroll & Graf, hc/trade pb, 1997) “You’ll Die Laughing” November 1940. “Walk Across My Grave” April 1942. ● Reprinted in Pure Pulp, Ed Gorman, Bill Pronzini, & Martin H. Greenberg, editors. (Carroll & Graf, trade pb, 1999) “Don’t You Cry for Me” May 1942. “Bullets Don’t Bother Me” August 1942. “Beat Me Daddy” November 1942. “Name Your Poison.” May 1943. Stories in DIME DETECTIVE [ML = Max Latin stories, all of which appear in the Mysterious Press trade paperback collection.] “The Gin Monkey” January 15, 1935. “The Devil’s Scalpel” November 1935. “Something for the Sweeper” May 1937. ● Reprinted in Hard-Boiled Detectives: 23 Great Stories from Dime Detective Magazine, Stefan Dziemianowicz, Robert Weinberg, and Martin H. Greenberg, editors. (Gramercy, hc, 1992) ● Reprinted in A Century of Noir: Thirty-Two Classic Crime Stories, Mickey Spillane & Max Allan Collins, editors. (New American Library, trade pb, 2002)  “Death Sings

a

Torch-Song” July 1937. “Death Sings

a

Torch-Song” July 1937.“Drop of Doom” December 1939. “Murder Down Deep” February 1940. “Murder in the Red” April 1940. “This Will Kill You!” August 1940. “Watch Me Kill You!” July 1940. [ML] “Come Up and Kill Me Some Time” October 1941. “Don’t Give Your Right Name” December 1941. [ML] ● Reprinted in The Hardboiled Dicks, Ron Goulart, editor. (Sherborne Press, hc, 1965; Pocket, pb, 1967; Boardman, UK, hc, 1967) “Have One on the House” March 1942. “Give the Devil His Due” May 1942. [ML] “Who Said I Was Dead?” August 1942. ● Reprinted in Hard-Boiled: An Anthology of American Crime Stories, Bill Pronzini & Jack Adrian, editors. (Oxford University Press, hc/trade pb, 1995) “You Bet Your Life!” September 1942. “You Can Die Any Day” December 1942. [ML] “Too Many Have Died” April 1943. “Charity Begins at Homicide” October 1943. [ML] “Take It from Me” December 1943. Stories in DETECTIVE TALES “Reprieve from Death” July 1936. “Satan’s Doll Shop” August 1936. “Paroled to Murder” September 1936. “Murder Medicine” October 1936. “Come Home and Die!” November 1936. “A Gamble in Corpses” March 1937.  “Death Stops the

Show” April 1937. “Death Stops the

Show” April 1937.“Cubes of Blackmail” August 1937. “Trail of the Talented Butcher” September 1937. “Judge of the Damned” October 1937 “Underworld Judge – and Jury” November 1937. “Charge It to the Corpse” January 1938. “Murder Walks Tonight” April 1938. “Corpse on the Hearth” May 1938 “The Judge Looks at Death” June 1938. “For They Would Gladly Die!” September 1938. “My Client, the Corpse” October 1938. “Oasis of Dying Men” March 1939. “Death Asked for Golden Slippers” May 1939. “Murder Highway #1” July 1939. “Children of Murder” September 1939. “Back Road to Death” October 1939. “The Corpse Lottery” January 1940. “No Miracles in Murder” June 1940. “Fear House” September 1940. “The Tale of the Homeless Corpse” June 1942. “Doctor Flame’s Murder Blackout” September 1942. Stories in DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY (**) “Black Death” May 18 1935. “The Girl with the Webbed Hand” August 24, 1935.  “Trip to

Vienna”

October 19, 1935. “Trip to

Vienna”

October 19, 1935.“One Man Died” January 18, 1936. “The Missing Legs” February 22, 1936. “Diamond Slippers” March 14, 1936. “Clues on Crutches” June 20, 1936. “Public Defender.” June 27, 1936. “Murder Harvest” September 12, 1936. “The Case of the Greedy Guardian” October 3, 1936. “Five to One Odds on Murder” February 6, 1937. “Top Hat Killer” June 26, 1937. “Beauty in the Morgue” July 31, 1937. “Indian Sign” September 18, 1937. “Mountain Man” October 2, 1937. “Devil Down the Chimney” December 11, 1937. “Cat’s Claw” January 8, 1938. “Murder Buried Deep” March 12, 1938. “Marriage is Murder” October 15, 1938. “Ideal for Murder” February 11, 1939. “The Lethal Logic” April 29, 1939. ● Reprinted in Dark Lessons: Crime and Detection on Campus, Marcia Muller & Bill Pronzini, editors. (Macmillan, hc, 1985) “A Vote for Murder” July 15, 1939. “Mud in Your Eye” October 14, 1939. “Never Say Die” November 11, 1939. “Cry Murder!” July 1944. [** Magazine had become FLYNN’S DETECTIVE FICTION by this date.] Stories in ACE-HIGH DETECTIVE “Upside-Down Man” August 1936. Stories in DETECTIVE STORY MAGAZINE “Hex on Horseback” January 1939. “Dance for the Dead” July 1940. “Crime at Hudson’s Hill” January 1942. Stories in DOUBLE DETECTIVE “String Him Up” February 1938. ● Not a short story but a 50,000 word novel which was later published in expanded form as Murder Picks the Jury (1947) . “Noose Around Your Neck” March 1938. “You Listen!” July 1938. [with Dwight V. Babcock] ● Reprinted in 101 Mystery Stories, Bill Pronzini, editor. (Avenel, hc, 1986) “Murder on the Mississippi” October 1938.  “Death of a Medicine

Man” February 1939. “Death of a Medicine

Man” February 1939.“Model for Murder” October 1939. Stories in NEW DETECTIVE “Till the Killer Comes” November 1951. Stories in THE PHANTOM DETECTIVE “The Rag-Tag Girl” May 1936. Stories in POCKET DETECTIVE MAGAZINE “Death’s Model” December 1936. “Bad Actor” February 1937. “Letters from Home” June 1937. Stories in PUBLIC ENEMY “Dancing Dimes” February 1936. “Hell’s Freight” April 1936. Stories in STRANGE DETECTIVE MYSTERIES “Idiot’s Coffin Keepsake” October 1937. “Beware Death’s Toiling Bell” November 1937. Stories from ARGOSY “Black Bandana” November 21, 1936.  “Blue

Bullets”

March 13, 1937. “Blue

Bullets”

March 13, 1937.“Mad Money” June 25, July 2, July 9, July 16, July 23 1938. [complete 5-part serial] “Jail Delivery” October 22, 1938. “Sand in the Snow” Apr 1, Apr 8, Apr 15, Apr 22, Apr 29 1939. [complete 5-part serial] “Holocaust House” Nov 16, Nov 23 1940. [two-part novelette featuring Doan and Carstairs] ● Reprinted in The Arbor House Treasury of Detective and Mystery Stories from the Great Pulps, Bill Pronzini, editor. Arbor House, hc, 1983. “Hang Him High” May 17, May 24, May 31, June 7, June 14, June 21 1941. [complete 6-part serial] “Murder – Do Not Disturb” February 2, 1942. “Tigers in the Sky” March 1943. “Rendezvous with the Russians” May 1943. “Wild Rubber Runs Red” September 1943. Stories from THE AMERICAN MAGAZINE “Swindle, Sweet And Simple” April 1949. Stories from COLLIER’S MAGAZINE “A Is for Annabelle” January 1, 1944. “Send Back Something” January 27, 1945. “Never Argue with a Civilian” May 5, 1945. “A Penny Saved Is Not Much” May 12, 1945. “The Beezlebub Blast” March 2, 1946. “Build Me a Bungalow Small” December 6, 1947. Stories from THE SATURDAY EVENING POST “Get Out and Get Under” January 1, 1944. “Not So Very United” August 26, 1944. “The Desperate Divorcee” September 30, 1944. “You Can Always Marry the Woman” April 13, 1946. “Just a Nice Quiet Title” June 8, 1946. “I’ll Tell My Mother” January 25, 1947. “Kelly Makes a Deal” May 17, 1947. [with W. T. Ballard] “What Will Marjory Say” October 25, 1947. “Defiant Lady” February 28, 1948. “A Beautiful Fraud” March 27, 1948. “Girl Hunt” July 10, 1948. “The Lady on the Highway” October 23, 1948. “The Captious Sex” January 8, 1949. [with Nancy Davis] Stories from COMPLETE STORIES “Marriage for Sale” April 1936. Stories from DIME WESTERN “A Gunsmoke Case for Major Cain” October 1940. NOTE: This was the basis for a Bill Elliott film called HANDS ACROSS THE ROCKIES (1941) – Davis’s only sale to Hollywood. Stories from FRONTIER STORIES “The Ghost of Murder Alley” December 1933 - January 1934. “Four Drops of Blood” February - March 1934 Stories from SHORT STORIES “Japanese Sandman” October 25, 1942. Stories from STAR WESTERN “The Gunsmoke Banker Rides In” July 1942. “Dead Man’s Brand” November 1942. Stories from THRILLING ADVENTURES “Dead Man’s Chest” November 1936. ***

SOURCES: John L. Apostolou, Norbert Davis: Profile of a Pulp Writer. Revised from its first appearance in The Armchair Detective, Vol. 15, No 1, 1982. Thanks also go to John for his assistance in pointing out several entries that were omitted in an early version of the bibliography. Bill Contento, The FictionMags Index. Michael L. Cook & Stephen T. Miller, Mystery, Detective and Espionage Fiction (1915-1974). Allen J. Hubin, Crime Fiction IV. www.abebooks.com ***

ALSO RECOMMENDED: A chapter on Davis in E. Hoffman Price’s memoirs, Book of the Dead: Friends of Yesteryear: Fictioneers & Others (Arkham House, 2001) – specifically, Chapter XIV, Norbert W. Davis, pp. 237-244 – contains some interesting biographical and anecdotal material. The book cover images and the photos above are from the collection of Bill Pronzini. Many of the pulp cover scans came from the website maintained by Phil Stephenson-Payne. YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. Copyright © 2006 by Steve Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors. Return to the Main Page. |