|

HELEN REILLY, by Mike Grost

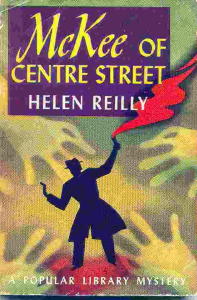

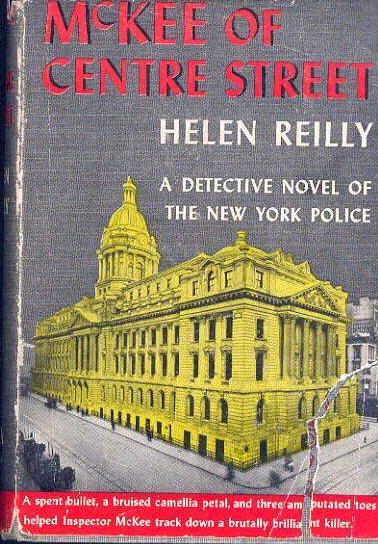

Reilly and Freeman Wills Crofts  Helen Reilly was a prolific author of mystery novels, whose career stretched from 1930 to 1962. All except her very earliest books feature New York City police Inspector Christopher McKee and were among the first American novels to stress police procedure. To what school do Helen Reilly's novels belong? This is not an easy question. In Murder for Pleasure (1941) Howard Haycraft emphasized that she was not an HIBK [Had I But Known] writer. This was true at the time; but later, she often included young society women in her tales, who were in jeopardy – a sign of HIBK influence on her later work. However such HIBK-like Reilly novels as The Opening Door (1944) and The Silver Leopard (1946) seem to me to be among Reilly's poorest works. There is an discussion of Reilly in Jon L. Breen’s excellent article on the history of the police procedural, in The Fine Art of Murder (1993). Breen argues that Reilly comes out of the Van Dine school, and he suggests that she is similar to Van Dine school writer Anthony Abbot, who also wrote about a New York City policeman, Thatcher Colt. I do not feel that Reilly’s police procedurals fall into easy categories. Beginning with The Cask in 1920, the novels of mystery writer Freeman Wills Crofts described the realistic, routine sleuthing of British policeman. They were immensely influential, both in Britain and abroad. Yet while Reilly’s works emphasize police procedure, she does not seem to be a Crofts-influenced writer. Her books seem very different from the police stories of Freeman Wills Crofts, in that they focus in turn on the operations of many different members of the police team, for example. Scenes alternate between those seen from the point of view of the police with those in which the POV is owned by civilians involved in the crime. This is very different from the tales told by Crofts, in which the viewpoint focuses steadily on Inspector French. Nor is Reilly especially interested in such Croftsian features as ingeniously faked alibis, detailed backgrounds, the “breakdown of identity,” clever criminal money-making schemes involving smuggling or forgery, or mosaic like investigations of past crimes.  Where Reilly

does resemble

Crofts is in

the purity of her approach. Her McKee

of Centre Street (1933) sticks to pure police procedure

throughout its length, with the same single-mindedness that Crofts

displayed in such books as The Box

Office Murders (1929). Also Crofts-like: the way we share

all of McKee’s thoughts and discoveries throughout the book, instead of

waiting till the end of the novel to get the detective’s ideas.

Reilly also shares Crofts’ internationalism: McKee of Centre Street has frequent

flashbacks to Columbia in South America, in the same way that Crofts

liked to explore continental Europe. The boat and ocean finale of

McKee of Centre Street

is also

reminiscent of Crofts. Where Reilly

does resemble

Crofts is in

the purity of her approach. Her McKee

of Centre Street (1933) sticks to pure police procedure

throughout its length, with the same single-mindedness that Crofts

displayed in such books as The Box

Office Murders (1929). Also Crofts-like: the way we share

all of McKee’s thoughts and discoveries throughout the book, instead of

waiting till the end of the novel to get the detective’s ideas.

Reilly also shares Crofts’ internationalism: McKee of Centre Street has frequent

flashbacks to Columbia in South America, in the same way that Crofts

liked to explore continental Europe. The boat and ocean finale of

McKee of Centre Street

is also

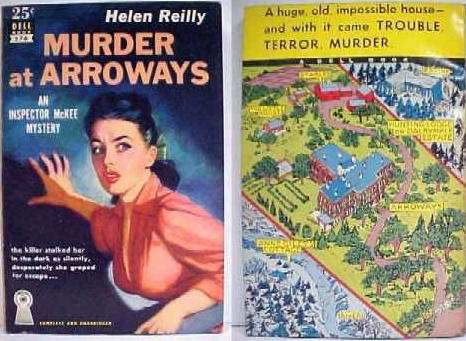

reminiscent of Crofts.Reilly does use scientific detection. She analyzes physical clues, and uses scientific techniques to identify material found at crime scenes, using the results to reconstruct the crime. The effect is closer to R. Austin Freeman than it is to Crofts, although Crofts did his own tour de force of this type at the opening of The Sea Mystery (1928). We also know that Reilly used the great real life German criminologist Hans Gross as a source, and so perhaps the scientific detection in her books derives far more from such real life examples than it does from detective writers such as Freeman and Crofts. Reilly’s interest in science and technology is consistent with that of others in the American school of detective fiction writing, such as Frederick Irving Anderson and William MacHarg. Mystery writers such as these were either were directly involved in the Scientific Detective Story of the era, or were allied, in the sense that their work often reflected the approaches of the Scientific school. One of the best uses of scientific detection in Reilly occurs in the opening of Mr. Smith's Hat. As in McKee of Centre Street, the science here is botany: McKee follows up clues involving plant fragments. Similar botany-oriented detection occurred in Anthony Abbot’s About the Murder of the Clergyman’s Mistress (1931). Reilly does indeed share with Abbot an interest in New York City police procedure, and scientific detective techniques. However, the tone and technique of Reilly seem very different from those of Abbot and the other Van Dine school writers. McKee is not a social aristocrat, unlike the Van Dine sleuths, and aside from his criminological expertise on botanical evidence, he has little of the Van Dine sleuth’s intellectual knowledge. Reilly also sticks closely to pure police procedure in a fashion that seems utterly different from the Van Dine writers’ more eclectic sleuthing techniques. Reilly and Frederick Irving Anderson As mentioned above, Reilly seems closely related to American writers of police detective tales such as Frederick Irving Anderson and William MacHarg. Both of these authors wrote short stories that appeared in slick magazines, such as Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post. Anderson’s tales flourished in the prosperous 1920s, and were full of extravagant fantasies of elaborate police investigations. MacHarg’s tales were mainly published during the 1930s and early 1940s Depression era and featured a plain realism in their settings among New Yorkers of all classes. Reilly’s novels seem closer to Anderson’s, but without the whimsy. Both Anderson and Reilly show a large team of police that perform a remarkable variety of tasks, including shadowing suspects, doing background checks, impersonation and undercover work, crime scene investigation and lab work. Both Reilly and Anderson highly relish the diverse personalities, skill sets and social backgrounds of their varied cops. Both authors’ police manage to spread a very wide net around the villainy under investigation, and both have enormous initiative and get up and go. Inspector McKee has the role of chief in Reilly’s world, just as Deputy Parr in Anderson’s. Lonely city apartments in run-down neighborhoods tend to be sites of violence in Reilly’s world. Reilly’s stories are like MacHarg’s and Cornell Woolrich’s in that they sometimes are set among poor people. These writers all use police detectives. Their poor people are not mobsters, unlike the hard-boiled writers of the pulps. Instead they are ordinary people who live in tenements and slums, have menial jobs, and cope with the Depression. McKee of Centre Street  McKee of

Centre Street (1933) is Reilly’s breakthrough novel, emphasizing

police procedure. The Centre Street of the title is the famed

headquarters of the New York City Police. The tale opens with a

description of the radio room there and is written in Reilly’s most

visionary style. There are descriptions of light on walls,

colors, sounds, the whole entirety building to abstract geometrical

patterns of light and sound. Such 3D abstractions remind one of

the visionary novels of William Hope Hodgson. McKee of

Centre Street (1933) is Reilly’s breakthrough novel, emphasizing

police procedure. The Centre Street of the title is the famed

headquarters of the New York City Police. The tale opens with a

description of the radio room there and is written in Reilly’s most

visionary style. There are descriptions of light on walls,

colors, sounds, the whole entirety building to abstract geometrical

patterns of light and sound. Such 3D abstractions remind one of

the visionary novels of William Hope Hodgson.Radio itself was a fairly new technology in 1934, and the chapter is also an expression of a universe created by high technology. The room contains maps showing the location of every police car in New York City; in many ways, it is a symbolic or virtual re-creation of the City itself. It seems like an early expression of Virtual Reality. It is also the brain center of police operations, and the chapter can be read as metaphors for the operation of the nervous system. Reilly emphasizes the efficiency of the police. This was a virtue highly prized in the 1930s, where it was associated with Modernism, science, and the Future. It also recalls Taylorism, the science of running factories efficiently according to mathematical and statistical methods. Reilly includes a document analyzing crime statistics for 1932 and 1931. Such a statistical approach also invokes Taylorist ideas. The police here are seen as a modern, factory like operation, using machines, mathematics and efficient organization to run their enterprise. It has been discussed whether Reilly’s books are ancestors of the modern police procedural novel. They certainly try to describe police procedure accurately and in detail. So in this sense, they certainly qualify. However, while many modern police procedurals stress the ordinary, human nature of the police, Reilly tries to convey the extraordinary nature of the police. Later chapters of the book depict a speakeasy where a murder has occurred. The speakeasy is also depicted in technological and organizational terms; the descriptions of its lighting effects, and the role they play in the murder, are almost as much a “sound and light show” as the opening police chapter. The electrician in charge of the lighting becomes a key player in the story. I cannot recall any other of the countless underworld nightclub tales of the 1930s that include an electrician as a character. This is a unique point of view created by Reilly. There is an odd contrast in imagery between the male and female characters. The women have often lost consciousness: the murdered woman looks as if she has simply passed out on the dance floor; suspect Judith Pierce is found fainted in the phone booth; and the janitor’s wife is asleep. By contrast, Reilly keeps emphasizing how alert the (male) police officers are. However, one of the male characters in the book will eventually lose consciousness, in a spectacularly written passage (Chapter 15). Throughout the book, Reilly’s extraordinarily vivid writing style will add an almost surrealistic clarity to her descriptions of typical daily life and location in New York City. Everything has a more real than real vividness that recalls the bright light in such painters as Dali and Magritte.  McKee of Centre Street sticks to its police procedure paradigm throughout its entire length. The book is extremely pure in its approach. Nearly everything in the book consists of the police examining a crime scene, finding some physical clue, and then using it to reconstruct the actions of the suspects and the victim. The police also use the eye-witness testimony of innocent bystanders, and the facilities of a huge police operation. They also do much trailing of the suspects, and even go so far to spy on them on occasion. The suspects all stonewall and lie to the police at every opportunity, so the suspects’ testimony plays only a small role in this book, as compared to, say, a typical Van Dine school novel. Although the suspects’ movements and actions are endlessly traced, they are on stage for only a small fraction of the time they would be in a conventional Golden Age novel, and they do not really come alive as characters. Throughout the novel there is vivid descriptive writing, especially of the buildings in which the suspects move, and of New York City lighting and atmosphere, as if to create a portrait of the city. This purity of approach has both strengths and weaknesses. It can be monotonous, and lack variety. But it does allow Reilly to explore her innovative techniques at length. There are two large manhunts in the second half of this novel; the first across New York City, the second in the Connecticut countryside. I tend to prefer the city one. It is written with all of Reilly’s visionary style of description. The countryside one is a bit of a shaggy dog story. It takes place in all the back ways and little used roads of a country area catering to tourists. It focuses on the locals who support the tourist industry, and their homes, camps and little known back paths. In this it is similar to the even longer and more elaborate country chase that occurs in Mr. Smith’s Hat. One does not want to oversell Reilly’s work. McKee of Centre Street lacks a clever plot solution. The end of the book takes only around five pages, and shows no ingenuity whatsoever. Sure enough, one of the characters did it. Reilly might as well have thrown a dart to pick this character, for it could have been any of the suspects. It is an anticlimactic end to a novel, all of whose merit has been its detection, not its puzzle plot. Reilly’s emphasis on typical scenes of daily life also deprive her books of the fabulous eccentricity that graces so many Golden Age novels. Reilly and the Pulp Style of Plotting Follow Me (1960) is a short, vividly written mystery novel, almost a novella. Some aspects of it remind one of the pulp story. It seems to show a version of the “pulp style of plotting,” with many disparate characters in the book engaged in criminal schemes. When any one thing bad happens, it is hard to tell which group of characters has done it. This style of plotting, occuring most often in hard-boiled fiction, was widely used by Black Mask authors of the 1920s and 1930s. At the end of Reilly’s book, there turn out to be no less than three groups of villains, and two of the groups have multiple bad guys in them, instead of solitary criminals. Reilly uses such all surrounding villainy to generate a sense of paranoia. This paranoia is also found in the pulps. It is interesting how gender plays a role in how this paranoia is perceived. When a tough detective is up against criminals at every turn, readers sometimes interpret this as a piece of serious social criticism. When Reilly’s sleuth, a pleasant, chic young New York housewife, encounters universal villainy, one can treat it as a “woman in danger” story. Actually the feel of paranoia is similar and intense in both Reilly and the hard-boiled novel.. The paranoia is an entire world view, and similar in both kinds of writers. Reilly’s heroine does not carry a gun, or beat people up, but she is remarkably similar in spirit to the tough guy detectives of the pulps. Other aspects of the story recall the hard-boiled pulps of the Black Mask school. The heroine gets roughed up when she explores a dangerous criminal lair toward the beginning of the book. This is very close to what happens to Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe or other tough PI’s when they explore some dangerous locale. Her serious injuries seem far removed from the genteel threats sometimes inflicted on HIBK heroines.  There are also

private

detective

characters who play a major role in the book. Another scene that

recalls the hard-boiled school: the canyon in Chapter 8, and what the

heroine finds there. This discovery is not the fixed aftermath of

a crime scene – no, the heroine-sleuth is plunged into a complex series

of events involving a crime in progress. When the dust clears,

she is left with a series of ambiguous clues about the events.

The whole thing is pure hard-boiled, and could have come right out of

1930’s Black Mask.

Raymond Chandler

loved to include scenes set in mysterious lonely canyons, and so did

Forrest Rosaire in “The Devil Suit” (1932). There are also

private

detective

characters who play a major role in the book. Another scene that

recalls the hard-boiled school: the canyon in Chapter 8, and what the

heroine finds there. This discovery is not the fixed aftermath of

a crime scene – no, the heroine-sleuth is plunged into a complex series

of events involving a crime in progress. When the dust clears,

she is left with a series of ambiguous clues about the events.

The whole thing is pure hard-boiled, and could have come right out of

1930’s Black Mask.

Raymond Chandler

loved to include scenes set in mysterious lonely canyons, and so did

Forrest Rosaire in “The Devil Suit” (1932).Looking further into this idea, it can be discovered that Reilly did have some contact with pulp magazines. Her second McKee novel, Murder in the Mews (1931), was serialized in Street and Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, and she published a handful of short stories in other pulps However, the novel serialization could easily have been arranged by an agent or a publisher, and Reilly’s degree of contact with the world of pulp writing may not have been great. And yet the murder victim in Mr. Smith’s Hat (1936) was grinding out Western stories for a fictitious magazine called Cowboy, which seems to be a pulp. One recalls that Craig Rice's protagonist in Murder Through the Looking Glass (1943) wrote for the science fiction pulps; that Lenore Glen Offord's series sleuth Todd McKinnon earned his living writing pulp detective stories; and that Dorothy L. Sayers’ Unnatural Death (1928) has a reference to Black Mask. All of these references to pulp fiction magazines by Golden Age writers seem to be by women authors. Perhaps this is just a meaningless coincidence. Or perhaps, male writers were more conscious of the low career status assigned to pulps, and avoided referring to them in their tales – career success is a traditional part of masculine self image. Reilly’s Techniques Reilly has a personal interest in architecture, that wonderful staple of Golden Age novels. Late in Follow Me, the heroine is held captive in a pink adobe house. Eventually, the roof of the building plays a role in the story. Similarly, in her early novel Murder in the Mews (1931), the roof of a building figures prominently. The characters in both books start out at the bottom, and eventually make their way to the top of the house. This earlier novel is extremely stilted. Reilly would become a vastly more lively writer as the years progressed. She had the gift of unrolling an ever more complicated plot, with each section providing some new, startling revelation about her characters. Her books, although they generate suspense, are true detective stories. The heroine of Follow Me, while she gets in jeopardy, is a real sleuth, and constantly attempts to both solve the mystery and to uncover more and more of the hidden truth. On re-reading, one can dip anywhere into Follow Me, and come up with a section that recalls itself vividly to memory. Reilly likes ambiguity. Many of the relationships in Follow Me can be interpreted in more than one way. So can most of the twists of the crime story. This adds to the paranoia of the plot. These different interpretations go off in numerous directions, so that suspicion is cast over everyone in the novel. A key scene in Chapter 11 has the heroine looking at two walls. One looks bluish, the other green, but it is an effect of light on identically colored walls. T his is a metaphor for the entire book. The everyday background of events in Follow Me should not disguise the quality of imagination in it. It is very difficult to come up with such relentless sustained ambiguity, one encompassing so many scenes and patterns. Color is often used when the heroine is about to have some revelation. Take as an example what she sees in the shop window in Chapter 7. These revelations have a visionary quality, as if they were illuminations of concealed truth, almost a mystic revelation. They often suggest hidden connections that were obscure before. This is a paranoiac world view – that everything is concealing some truth that could speak. It is also the sign of a real detective. Reilly’s heroine is a genuine detective, always motivated above all by the desire to learn the truth, and always uncovering more and more of it. The opening scientific detection in Mr. Smith’s Hat turns into a full fledged “revelation” of the kind found in her later work. The revelation involves color and form. It is one of the best pieces of imagery in her work. Staircase 4 (1948-1949) shows Reilly adopting and using techniques of 1940s suspense. Chapters 6 and 7 show the heroine being menaced in the GASLIGHT tradition, with someone trying to make her believe she has lost her mind; while Chapters 11 and 12 depict her heroine sleuthing for a mystery witness through endless streets of New York City, in the tradition of Cornell Woolrich’s Phantom Lady (1942). The heroine got the clue for this search earlier, when she recalled a new image about a past encounter (towards the end of Chapter 5). This newly illuminated memory is in Reilly’s visionary tradition. Staircase 4 also has some excellent descriptions of the lights of New York City, especially in twilight, after dark and in the rain. These show Reilly’s power to evoke effects of light and color.  Reilly’s Characters Reilly is often interested in formerly well-to-do New Yorkers who are downwardly mobile. Sometimes these people are very open about their sea change. One thinks of the victim in Mr. Smith's Hat (1936), who has abandoned his snooty relatives to life a life of drinking and bohemianism, or the penniless young society woman in The Opening Door (1944) who leaves home and starts a book store and glove shop to support herself, over her snobbish family’s fierce objection – they think she should have tried to marry for money instead. This young woman is clearly admirable, while the drunk is probably reprehensible. However, one has a distinct suspicion that Reilly is highly sympathetic to both. The treatment of the young woman has a feminist strand – her going to work is seen as admirable by the author, despite society’s objection. Similarly, the young widow in Follow Me plans to get a job, despite her friend’s protests. All of these open characters tend to be non-suspects. They are either victims, like the drunk, or viewpoint characters, like the heroine of The Opening Door and the young widow in Follow Me. They are marked as “innocent” in the mystery puzzle plot, and morally sympathetic in the author’s world view. A second kind of downwardly mobile character in Reilly is far less open about it. These are suspects who keep up a big front, and who live the lives of upper class New Yorkers, but who are actually quite strapped for money. These characters tend to be suspects in Reilly’s books. At first glance, they seem to be quite polished. They tend to be men, well dressed, sophisticated, and with upper middle class jobs. However, they are spending way above any income they have, and the reader discovers that these initially upper crust looking people will do anything for money. These characters include the father and the brother in The Opening Door, for example, and most of the heroine's circle of “friends” in Follow Me. Reilly’s treatment of these people as suspects in the puzzle plot is also mirrored in her negative moral and social view of them. They are always introduced in the plot as “typical” upper middle class people, and only later do we learn their flaws. This tends to suggest that most upper middle class people are essentially fakes, polished on the surface with their upper class clothes and status symbols, but far less solid underneath. All the downwardly mobile characters fit in with Reilly’s themes of ambiguity and hidden truth. They look one way socially, but in fact their real lives and status could be quite different. They have a double role. They are as ambiguous as are both the relationships and the mystery plot developments in Reilly’s work.  Reilly’s Last Novels Reilly’s Last NovelsThe Day She Died (1962) is Reilly’s last novel, and it returns to the New Mexico locations of Follow Me (1960). Reilly lived in New Mexico in her later years, and these two books are clearly based on personal observation. The Day She Died avoids HIBK mannerisms. It is a tale of pure detection, and the point of view taken is almost entirely that of two detectives. But conversely the novel is one of Reilly’s works that most closely follows the traditions of Mary Roberts Rinehart. It takes place in an isolated country house, one that is full of sinister events, much like the one in Rinehart’s The Circular Staircase (1907). Many aspects of the characters’ personal lives are ones that are familiar to us from Rinehart’s fiction. Its format also follows that of J. B. Priestley’s The Old Dark House (1927): a group of strangers taking shelter in a crumbling old country house from a terrible rain storm. In this case, the old house is an ancient adobe ranch, a relic of New Mexico’s earliest days. Reilly describes the storm, the New Mexico landscape, and the ancient house with tremendous vividness. These scenes have the visionary quality found in Reilly’s best writing. Later chapters take us into the cities of modern New Mexico, a pleasing contrast. Summary Helen Reilly’s reputation has perhaps suffered from writing too many HIBK style novels in the middle of her career. But her best works are original contributions to detective fiction. McKee of Centre Street is one of the best early police procedure novels, written with an almost hallucinatory intensity of description. And her later books set in New Mexico, the dynamically told Follow Me, and her final novel The Day She Died, also show originality of style. A writer whose best works read like no others, Reilly is long overdue for new readers. This article is slightly revised from one that appears on Mike Grost’s own website, A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection. Some additional discussion about Helen Reilly’s novels will be found in the Readers Forum. _________________ BIBLIOGRAPHY: HELEN REILLY (1891-1962) - compiled by Steve Lewis Helen Reilly [nee Kieran]. Married to artist Paul Reilly, mother of four daughters, including mystery writers Ursula Curtiss and Mary McMullen. Her brother, James Kieran, also wrote mystery fiction. President of MWA, 1953. US Editions Only * = Inspector Christopher McKee The Diamond Feather*. Doubleday Crime Club, 1930; hardcover reprint: Grosset & Dunlap, n.d. Magazine appearance: Triple Detective, Summer, 1950. Comment: Only five copies of the Crime Club edition are listed on ABE. The Thirty-First Bullfinch. Doubleday Crime Club; 1930. Magazine appearance: Thrilling Mystery Novel Magazine, March 1946. Comment: Again only five copies of the Crime Club edition are listed on ABE. Man with the Painted Head. Farrar & Rinehart, 1931. Magazine appearance: Detective Novel Magazine, Spring, 1948. Comment: The four copies of the Farrar edition listed on ABE range in price from $100 to $245. Murder in the Mews*. Doubleday Crime Club, 1931; hardcover reprint: Collier, n.d. Paperback reprints: Detective Novel Classic #23, ca.1943; Popular Library #259, ca.1950; Macfadden, 1966; Manor, 1974. Advance magazine appearance: serialized in Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, June 20, June 27, July 4, July 11, July 18, July 25, 1931.  The Doll’s Trunk Murder. Farrar & Rinehart, 1932; hardcover reprint: Grosset & Dunlap; n.d. Paperback reprint: Popular Library #211, 1949. Magazine appearance: Triple Detective, Winter, 1948. Comment: The notorious “bondage” cover on the paperback edition was done by well-known pulp artist Rudolph Belarski. McKee of Centre Street*. Doubleday Crime Club, 1934; hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1943. Paperback reprint: Popular Library #33; ca.1944. The Line-Up*. Doubleday Crime Club; 1934; hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1942. Paperback reprints: Macfadden, 1967; Manor, 1977. FOOTNOTE. Dead Man Control*. Doubleday Crime Club, 1936; hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press: 1937. Paperback reprints: Macfadden, 1964; Manor, 1974. Mr. Smith’s Hat*. Doubleday Crime Club, 1936; hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, n.d. Paperback reprints: Popular Library #48, ca. 1945; Macfadden, 1968; Manor, 1977. File on Rufus Ray. William Morrow & Co., 1937. Oversized cardboard folder. Crimefile #2: “This file contains the complete dossier of a crime, with every clue and item of evidence preserved in its original, physical form, exactly as it might have been received at Police Headquarters. The crime was a murder. The police solved it. Can You?” Included are facsimiles of “evidence” such as letters, confetti, cigar ashes, button, photographs, telegrams, etc. The solution is included in a sealed envelope. All Concerned Notified*. Doubleday Crime Club, 1939; hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1940. Paperback reprints: Century #29, 1945; Macfadden, 1964; Manor, 1974. Advance magazine appearance: Cosmopolitan, May, 1939. Dead for a Ducat*. Doubleday Crime Club,1939. Paperback reprint: Popular Library #56, 1945. Death Demands an Audience*. Doubleday Crime Club, 1940; hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1941. Paperback reprints: Popular Library #7, ca.1943; Macfadden, 1967; Manor, 1974. Murder in Shinbone Alley*. Doubleday Crime Club, 1940; hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1941. Paperback reprints: Popular Library #20, ca.1944; Macfadden, 1964; Manor, 1974. The Dead Can Tell*. Random House, 1940. Paperback reprint: Dell #17, ca.1943, mapback. Mourned on Sunday*. Random House, 1941. Paperback reprint: Dell #63, ca.1944, mapback. Three Women in Black*. Random House, 1941. Paperback reprints: Dell #114, ca.1946, mapback; Dell #709, 1953. Name Your Poison*. Random House, 1942; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #148, ca.1947, mapback. The Opening Door*. Random House, 1944. Paperback reprints: Dell #200, ca.1947, mapback; Dell #917, ca.1956; Ace Double #G518, ca.1965, bound with Follow Me. Advance magazine appearance: serialized in The Saturday Evening Post, Sept 25, Oct 2, Oct 9, Oct 16, Oct 23, Oct 30, Nov 6, Nov 13, 1943. Murder on Angler’s Island*. Random House, 1945; hardcover reprints: Grosset & Dunlap, n.d.; Collier [Front Page Mystery], n.d.; Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #228, ca.1948, mapback. Magazine appearance: Detective Novel Magazine, June 1946. The Silver Leopard*. Random House, 1946; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #287, ca.1949, mapback. Magazine appearance: Mystery Book Magazine, Jan 1947. “The Phonograph Murder*.” Short story, Collier’s, Jan 25, 1947. Reprinted: The Saint Mystery Magazine, March 1955.  The Farmhouse*.

Random House, 1947; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d.

[3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #397, ca.1950, mapback. The Farmhouse*.

Random House, 1947; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d.

[3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #397, ca.1950, mapback.“Dark Exit.” Novelette, Mystery Book Magazine, Fall 1948. Note: See the entry for “Black Reminder” below. “Perilous Escort.” Novelette, Short Stories, October 25, 1948. Reprinted as “The Perilous Journey,” Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, May 1962. “Black Reminder.” Story, Mystery Book Magazine, Spring 1949. Note: Both this story and “Dark Entry” may have been expanded to later novels, but which, if any, is not known. Whether Inspector McKee appears in either or both is also unknown. Staircase 4*. Random House, 1949; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #498, ca.1951, mapback. Murder at Arroways*. Random House, 1950; hardcover reprint: Mystery Guild [book club], n.d. Paperback reprint: Dell #576, ca.1952, mapback. Appeared serially in several newspapers as “The Black Ring.” Lament for the Bride*. Random House, 1951; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #621, ca.1952, mapback. The Double Man*. Random House, 1952; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #732, ca.1953. The Velvet Hand*. Random House, 1953; hardcover reprint: Mystery Guild, n.d. [book club]. Advance newspaper appearance: Star Weekly [Toronto], Dec 20, 1952. No paperback edition. Tell Her It’s Murder*. Random House, 1954; hardcover reprints: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]; Walter J. Black, n.d. Paperback reprint: Bestseller Mystery #B-201, n.d. [unabridged]. Compartment K*. Random House, 1955; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprints: Ace #G-546, ca.1963; Macfadden, 1971; Manor, n.d. The Canvas Dagger*. Random House, 1956; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprints: Bantam #1858, 1959; Ace Double #G-531, ca.1965, abridged, bound with Not Me, Inspector; Macfadden, 1970; Manor, 1974. Ding Dong Bell*. Random House, 1958; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprints: Ace Double #G-528, ca.1965, bound with Certain Sleep; Macfadden, 1971, Manor, 1974. Not Me, Inspector*. Random House, 1959; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Ace Double #G-531, ca.1965, abridged, bound with The Canvas Dagger; Macfadden, 1971. Follow Me*. Random House, 1960; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in1volume]. Paperback reprints: Ace ca. #G518, 1965, bound with The Opening Door; Macfadden, 1971. Advance newspaper appearance: Star Weekly [Toronto], May 21, 1960. Certain Sleep*. Random House, 1961; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprints: Ace Double #G-528, ca.1965, bound with Ding Dong Bell; Macfadden, 1971; Manor , 1974. Advance newspaper appearance: Star Weekly [Toronto], June 17, 1961. The Day She Died*. Random House, 1962; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprints: Ace #G-536, ca.1965; Macfadden, 1970. Comment: The Macfadden edition is surprisingly hard to find. Only one copy is listed on ABE ($14.35). Books written as by Kieran Abbey. Run with the Hare. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1941. Comment: Extremely scarce. The two copies listed on ABE are priced at $175 and $300 respectively. And Let the Coffin Pass. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1942. Comment: Also very scarce, but the three copies listed on ABE range in price from $49.50 to only $70. Beyond the Dark. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1944; hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, n.d. [3-in-1 volume]. Paperback reprint: Dell #93, ca.1945, mapback. References: www.abebooks.com Michael L. Cook, Monthly Murders Michael L. Cook & Stephen Miller, Mystery, Detective and Espionage Fiction: A Checklist Allen J. Hubin, Crime Fiction IV www.magicdragon.com ( The Ultimate Mystery / Detective Web Guide ) FOOTNOTE. From Bob Riedel: I noticed that the chronological order of two titles are transposed. McKee of Centre Street and The Line-Up both came out in 1934, as you had noted, but McKee of Centre Street was published first. The first edition bears two publisher’s notices that “... The Line-Up will appear in the fall of 1934.” And although the McKee character appeared in two earlier novels, the promotional text in McKee of Centre Street goes to some lengths to present the book as “the first of the cases of Inspector McKee of Centre Street ... ,” with the strong implication that this is the first McKee book. Thanks also to Peter Enfantino, Richard Hall and Phil Stephensen-Payne for the corrections and additions to the bibliography which they provided. INQUIRY. As indicated in two notes above, there are still some open questions regarding Helen Reilly’s short fiction. Any additional information would be appreciated. _____________________________________ YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME.

Copyright © 2005 by Steve

Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors.

Return to

the Main Page.

|