STEWART STERLING: KING OF THE

SPECIALTY DETECTIVES, by Richard Moore

Discovering new writers is

always a highlight of attending a Bouchercon. Discovering new

“old” writers is just as exciting to me. This year I picked up a

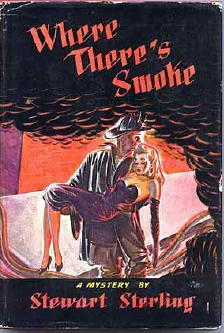

very nifty Dell mapback of Where

There’s Smoke, a reprint of a 1946 novel by Stewart

Sterling. Art Scott, paperback cover art expert extraordinaire,

came along as I was standing at the dealer’s table admiring the Dell,

and he nodded in appreciation at the condition. At this point I

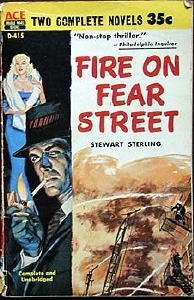

raised my other hand which held Ace Double D-415, displaying the side

featuring Sterling’s Fire on Fear

Street, a reprint of a 1958 novel originally published by

Lippincott. “Apparently,” I said, “It’s a series.” Discovering new writers is

always a highlight of attending a Bouchercon. Discovering new

“old” writers is just as exciting to me. This year I picked up a

very nifty Dell mapback of Where

There’s Smoke, a reprint of a 1946 novel by Stewart

Sterling. Art Scott, paperback cover art expert extraordinaire,

came along as I was standing at the dealer’s table admiring the Dell,

and he nodded in appreciation at the condition. At this point I

raised my other hand which held Ace Double D-415, displaying the side

featuring Sterling’s Fire on Fear

Street, a reprint of a 1958 novel originally published by

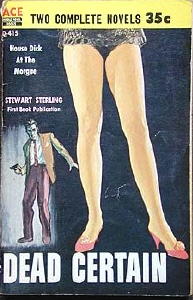

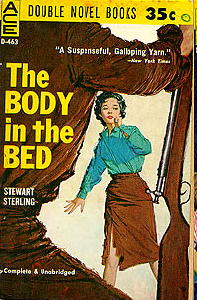

Lippincott. “Apparently,” I said, “It’s a series.”Art gave me a quick surprised glance. “You’ve never read any of the Fire Marshal Pedley series?” My confession of ignorance clearly caused his estimation of me to sink. Oh, I had seen the name, and somewhere I had a novel by him that had never tempted me to read. Art patiently explained to me that Sterling came out of the pulps and specialized in specialty detectives. His best known character was Fire Marshal Pedley with a career that began in the pulps, jumped to hardback novels in the 1940s and continued into the 60s. Art said Sterling also had a series featuring a “house dick” by the name of Gil Vine. I flipped the Ace Double over, and there was Dead Certain on the other side, featuring two Gil Vine novelettes. I barely got home before I hit ABE and ordered more by Sterling, the best-known by-line of Prentice Winchell (1895 to 1976). I later learned that Winchell wrote for the pulps and for radio before publishing his first novel. In fact, the jacket copy on his first novel Five Alarm Funeral (Putnam, 1942) says the Fire Marshal Pedley story was “…the work of one of the leading radio script writers in the business, a man whose name is known to literally millions.” I take that as more than a little overstatement, since few non-performing script writers were known to many in the public. Perhaps the copywriter saw the Winchell name and got carried away. I have seen no indication that Prentice Winchell was related to Walter Winchell. Gil Vine Expecting Sterling reinforcements to arrive in the mail, I settled in to read the Ace Double. First up, Gil Vine. This is a first person series, and the hotel background feels authentic. One book I ordered was a Pyramid Books edition of the 1954 non-fiction book, I Was a House Detective, by Dev Collans with Stewart Sterling. So I know Sterling did some research. The two Vine stories in Dead Certain feature a tabloid style manner of expression that seems far more real to me than most of the other attempts I’ve read to produce this dialect. After stopping a woman’s suicide attempt, Vine says: “She tried to fly… Tim grabbed her before she spread her wings.” Here’s another randomly chosen example: “Larry’s cagey enough not to let everything he knows leak out through his mouth...” I tire quickly of the Damon Runyon-type chatter, but I had no problem with this.  There is one aspect of the stories that bothered me. I can suspend disbelief with the best of them in order to enjoy a story. But both these Vine stories had him delaying notifying the police of very serious crimes, even while additional crimes were committed. Vine’s job is to protect the hotel’s reputation, and while he generally will not let a criminal go free, he will do most anything to protect the hotel. Understanding that this was a different era, I cannot believe that the police in either of these stories would not have thrown him in jail for numerous crimes, even if he did solve the murder. It is one thing for a private eye to withhold evidence or obstruct investigations, but an employee of a luxury hotel could not do this without serious repercussions with the authorities and with lawsuits. Maybe I am too picky or getting to be a wimp in my old age because these stories, despite a sometimes breezy manner, are quite tough. And while in the real world the stunts pulled could not possibly be as overt as Vine’s, his character is otherwise believable and remarkable for being openly amoral. He is not traveling these mean streets to right wrongs. His only concern is protecting the image of the hotel that employs him. The first story begins with a woman guest saying she was raped and describing one of the hotel’s richest and best known guests as her attacker. This is a hotel’s worst nightmare. Vine calls in the house doctor who asks, “Am I supposed to verify this assault?” Vine answers, “No. Knock her out. Slip her a mickey. Enough to keep her asleep while I do some investigating.” So Doc slips her the mickey and within a few minutes (and about three pages) the woman dies of an overdose. Doc’s shot was too strong or, more likely, she had something else in her system that made the additional narcotic lethal. There is a fleeting moment when Doc feels a bit bad about it, but that’s about it on the regret front. I love Gil Vine’s reaction. “My first instinct was to figure it a break for the house. After nine years on security, it’s second nature to keep the hotel’s name from being plastered with guk. Offhand, this seemed like a perfect opportunity to keep it clean.” He continues to muse on the fact that the girl had only told the doc and himself about the rape. That fact need never come out. Finally, he decides that it would eventually have to be reported. “It wasn’t conscience; I haven’t had my conscience out of mothballs since ’08. Call it pride. It griped me to have some bastard get away with something as raw as that, right under my nose.” Still a little later Vine asks Doc if he could certify the death as being from natural cause, but Doc answers “Of course not.” My opinion on the Gil Vine series based on these two stories placed it above average in many ways. Yet, I need to read a few more to make a firm judgment on the series.  Fire Marshal Pedley Fire Marshal PedleyAs for Fire Marshal Pedley, he is the real deal, and I will follow him into many more burning buildings. Told in the third person, Pedley is a big bulldog of a guy who moves forward in a straight line as he pursues arsonists. “Moves” is the action word here, and he not only moves, he plunges. In Fire on Fear Street Pedley gobbles bennies to keep going as he works around the clock to catch an arsonist trying to torch a tenement neighborhood. What I like about old Pedley is that Sterling allows him to be human. Trying to collar an old man, Pedley’s ear is bitten and torn and bleeds for half the book. About the time it stops bleeding, a patrolman mistakes the fire marshal for a prowler and slugs him with a nightstick, which starts the bleeding anew. As Pedley pops the bennies and forces himself to go on, it is evident that he is no longer operating at full capacity and eventually makes a major mistake. But nothing will stop him from working through his mistakes and eventually stopping the arsonist. I like this big guy! Skipping to my other Pedley novel, Where There’s Smoke, there is this description of his method: He knew only one way to go at a thing like this. Keep asking questions. With his eyes, when he could. With his mouth, when he had to. If you kept on asking questions and getting answers, the right one would be among them sooner or later. The most notable aspect of the Fire Marshal Pedley novels is the pace. I love a writer who knows how to keep a novel moving, and Sterling is one of the best at this I’ve ever read. Today’s mail brought me a couple of additional Sterling novels, and on the cover of one, Anthony Boucher compares the pace to Erle Stanley Gardner’s, who was renowned for his fast-paced narratives. Sterling was not known as a stylist, but he can be graphic in descriptions, such as this of a fire victim: Blackened lips curled back against the teeth in a clown’s grimace – a man whose face looked as if minstrel make-up had cracked and peeled from his skin, whose head was covered with charred fuzz where there had been hair. When Pedley knelt down in a puddle of water to examine the body, there is this: Pedley put a palm to the dead man’s chest, pressed gently. A tiny feather of smoke trailed from the blackened lips. And while the prose rarely soars, there are moments when Stewart captures a gritty city feeling: He stood up, looked at the sky. The ugly glow was gone from the underside of the low-hanging clouds; the smoke drifting upward had little heat beneath it to give it wings. The boys had the blaze in hand. The pumpers were uncoupling. Soot-smudged men were taking up – handling the ice-sheathed canvas as cautiously as if they were juggling butcher knives. Gongs clanged the recall for hood-and-ladders. Motors roared. Police whistles shrilled. Sirens began their warning wail.... The crowds at the fire line were already thinning. Hose trucks and combinations were rolling out from the curb, sliding away into the early dusk with bloodshot eyes. I now have another Vine mystery in hand, thanks to the mail. Alibi Baby in an Avon paperback from 1955. What a cover! Picking up the nearest edition of Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers, I wasn’t surprised to find a comprehensive write-up and publication history. I wasn’t even surprised to see that it was written by Art Scott. The article gave me a broader view of Winchell’s career. He did like his specialty detectives. Aside from Vine and Pedley, there was another series published under the name Spencer Dean that featured a department store detective by the name of Don Cadee. An early one-shot novel with the wonderful title Down among the Dead Men (Putnam, 1943) was about the harbor police. He also managed to work into his writing schedule two paperback originals for the great Gold Medal series published under the name Dexter St. Clair. I have seen little describing Winchell’s personal life. The bio in the Ace Double says “He lives aboard his Chesapeake Bay cruiser at the Municipal Yacht Basin in Daytona Beach, Florida.” Before he turned to novels, the Sterling Stewart by-line was used on a series of nine stories in the legendary magazine, Black Mask, which were labeled “Special Squad” stories. The 1939-1942 series highlighted different “special” squads from homicide to the bomb squad. I have yet to read any of the series but the descriptions make them sound like examples of early police procedurals. It turned out my Las Vegas buying spree did include one pulp with a Sterling story. This was purely by chance as I bought it prior to buying the novels and hearing Art Scott’s remarks on the author. The pulp was Top Detective Annual with a banner across the top “The Year’s Best Mystery Story Anthology” and just underneath that “1952 Edition.” After getting it up to my room, I looked at it more carefully and was annoyed to find that I was wrong to believe my lying eyes. It wasn’t a “best of the year” annual at all, and in fact I don’t believe there is a story from 1952 contained within. It is a reprint pulp that has an assortment of stories from the Thrilling Publications pulp chain with editorial director the legendary Leo Margulies. Stories from as far back as 1935 were selected, from such mags as Thrilling Mystery, Thrilling Detective, Thrilling Adventures, Phantom Detective, etc. My irritation passed as the contents included new-to-me stories by Dwight Babcock, Fredric Brown, Wyatt Blassingame, Murray Leinster, William Campbell Gault, and among the group, a lead story by Stewart Sterling.  Gil Vine, Pulp Private Eye Gil Vine, Pulp Private EyeIt was only after I returned home that I noticed the Sterling story and was pleased to discover it was a Gil Vine story “The Glass Guillotine” from the November 1940 issue of Thrilling Detective. It’s long (over 30 pulp pages), and the opening chapter caught my attention. The story predates Vine’s hotel security career and is told in the third person, unlike the first person novels that came after. Vine is introduced as a private eye who has had a one-man agency since he left the FBI five years before. I have yet to find any reference to the FBI in the Vine novels. The most notable background I’ve found in the novels is that Vine went through the Guadalcanal campaign in the Pacific. In the novels, despite Vine’s colorful lingo, he is portrayed as something of a sophisticate. It may be that Sterling made these choices deliberately, as Vine was at the crossroads of a cultural clash between the Fifth Avenue hotel setting and the more earthly chores of being a house detective. Then again, Sterling may have scattered the high-brow and lowbrow references willy-nilly. In one of the later stories, Vine dines on foie gras Strasbourg, venison steak sandwiches, and Stilton-in-Port. This is not a meal I would have chosen, although I had some rather odd combinations when I lived in Brussels, but Vine enjoyed it immensely. Vine will also throw in an italicized non-English word, sometimes plopping it down into otherwise Americanism patter, such as when he once described his hotel thus: “The Plaza Royale is pretty generally classified as an upper-crust caravanserai.” Two lines later he explains that his hotel doesn’t cater to the convention trade. “...the high-powered wheels who flock to our Crystal Room would put on a flap if we let in the whoop-de-doo bunch for one of those water-pistol squirting get-togethers.” I’m trying to imagine Vine saying that with his mouth full of foie gras. The pulp novel presents a simpler Gil Vine. He’s the classic tough-guy private eye sitting at a table in “a disreputable joint” called the Bachelor’s Club (so named because no one would ever take his wife there). The plot is rather unusual for a pulp novel. Vine spots the leading candidate for the presidential nomination of a major party now holding its convention in the city. He is a member of the cabinet who Vine knew well from his years with the FBI. Vine is stunned to see the dignified man in his early sixties at a ringside table, sloppy drunk and clutching a “honey-haired wench.” Knowing that reports of this behavior would sink the statesman’s candidacy, Vine makes his way to the table to rescue him, just as a photographer appears with a camera. The blonde clutches the old guy and strikes a pose for the picture, but Vine steps in the way and knocks the camera to one side. When objections are made by the bouncers, Vine pulls his .45 and stands them off while he escapes with the candidate and the blonde. As sometimes happens in the pulps, the blonde turns out to be an okay dame, and Vine eventually enlists her help. And he needs a lot of help, because they no sooner climb into a cab than it’s rammed by a laundry truck and the old guy is slammed into the meter box. So instead of continuing on to the Turkish Bath where Vine was going to sober the guy up for the big speech the next day, he directs the cabbie to steer the still-functioning taxi to a doctor Vine knows. Doc Easter “was not drunk but he had been drinking” but the observant Vine noted that “the fine square-fingered hands were steady.” And drunk or sober didn’t matter much anyway because Doc took one look and said “This man’s dead.” Now at this point I was disappointed to see the old boy wiped out so quickly as the political plotline was interesting. But I have learned with Sterling that he will kill characters quite unexpectedly. The writing in this story is cruder than in his later novels, and given the penny a word or less rates, that isn’t too surprising. I doubt that many pulp writers did much rewriting – Chandler being one obvious exception. But the absolute hell-bent pace carries the reader past bumpy spots in the writing and scattered clichés, and as the reader whizzes along, the story takes several odd turns. The pace and the impossible-to-anticipate plotting reminded me of an A. E. van Vogt science fiction novel from his heyday in Astounding. Van Vogt wrote everything in short scenes, and he used every idea that came to his mind. He feared that if he rejected an idea, it might block the flow and create a mental logjam. So he would let a central character die because he trusted his imagination would figure out a way to revive him in the next chapter. Harder to do in a mystery, but back to Gil Vine. He’s standing there mourning the death of his favorite statesman when Doc Easter murmurs “mistake somewhere” and uses one of those fine square-fingered hands to snatch the hair off the corpse’s head. A wig! And the nose comes off as well. There’s a young man underneath! An actor, for Christ’s sake. The blonde confesses that she and her dead pal were hired to act out the scene in the club. Vine stuffs the wig and the nose in his pocket, asks Doc to hold off just a little bit before calling the cops, grabs the blonde and heads back to the nightclub. If that ain’t the dead statesman, then somebody is holding him. He has to be out of circulation or the phony scandal wouldn’t work. I won’t go into much more detail on a story no one else will be able to read, but the scene shifts from the nightclub to a bowling alley to a ritzy hotel to a huge commercial laundry and finally to the convention hall. Vine is in separate knockdown fist fights with a political boss, the nightclub owner and his partner, the laundry truck driver, the laundry truck driver’s giant friend and a chauffeur. Actually, some of these guys he fights more than once, and two or three he shoots when they pull weapons in the course of the fist fights. He rescues one minor character from a torture chamber, is given a mickey (nicknamed “the glass guillotine”), and gets the statesman’s wife to give an emotional statement to the national political convention that buys time while he searches for her husband. The penultimate scene is in this huge laundry where Vine and the finally located cabinet secretary are trapped in a tightly sealed room where the villain pipes in hot steam that well-neigh cooks the two before Vine can manage their escape. The final scene has Vine producing the rather worse-for-the-wear candidate in time to receive his party’s nomination. The crooked political boss is confronted by Vine but he plunges into the crowd before the .45-waving Vine can stop him. Rather than chase the fleeing man, Vine goes to the podium, grabs the microphone, and announces to the delegates who was responsible for the kidnapping and attempted murder of their revered nominee. “For a moment the crowd near one of the exits appeared to mill around like cattle in a stampede. Then there was a shrill, thin cry of terror.” Whew! I think I’ve already gotten my money’s worth of entertainment from that old reprint pulp magazine, and there are eleven more stories still to be read. The character of Gil Vine described in this pulp story is very different from the hotel security chief pictured in the novels. I picked up one of my newly arrived examples to check and found The Body in the Bed (Lippincott 1959), opening with Vine finishing a gigot d’agneau for lunch. The pulp Gil Vine would have been satisfied with a leg of lamb. Here are the Fire Marshal Pedley novels:  Five Alarm Funeral.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, hc, 1942 Five Alarm Funeral.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, hc, 1942Handi-Book#23, pb, 1944

Where There’s Smoke.

J. B. Lippincott, hc, 1946Dell #816, pb, 1954 Ace Double D-515, pb, 1961. Bound with Robert Colby Kill Me a Fortune Unicorn Mystery Book Club, hc,

April 1947. Bound with Edward Ronns Terror in the

Town,

George Harmon Coxe Dangerous

Legacy & David Dodge It Ain’t Hay

Dell #275 (mapback), pb, 1949

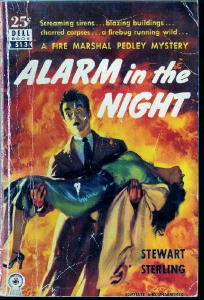

Alarm in the Night. E. P. Dutton, hc, 1949 Unicorn Mystery Book Club,

hc, December 1949. Bound with Amber Dean Snipe Hunt,

Lenore Glen Offord The Smiling

Tiger & Jean Leslie The Man Who

Held Five Aces

Dell #513 (mapback), pb, 1951

Nightmare at Noon. E. P. Dutton, hc, 1951 Unicorn Mystery Book Club, hc,

July 1951. Bound with Frances Crane The Polka Dot

Murder,

Douglas Heyes The Kiss-Off

& Jack Williamson Dragon’s Island.

Dell #683, pb, 1953

The Hinges of Hell. Ives Washburn, hc, 1955 No US paperback edition.

Candle for a Corpse. J. B. Lippincott, hc, 1957 Avon #835, pb, 1958, as Too Hot to Kill

Fire on Fear Street. J. B. Lippincott, hc, 1958 Ace Double D-415, pb, 1960.

Bound with Dead Certain

(see below).

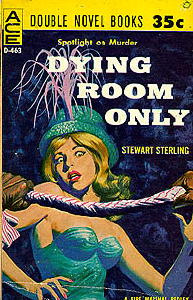

Dying Room Only. Ace Double D-463, pb original, 1960. Bound with The Body in the Bed (see below).  Too Hot to Handle. Random House, hc, Sept 1961 The Mystery Guild (book club),

hc, Nov 1961.

No US paperback edition. Here are the Gil Vine novels: Dead Wrong. J. B.

Lippincott, hc, 1947

Dell #314 (mapback), pb, 1949

Dead Sure. E. P. Dutton, hc, 1949 Unicorn Mystery Book Club, hc,

February 1949. Bound with Jean Leslie Shoes for My

Love,

Day Keene, Framed in Guilt

& Anthony Morton A Rope for the

Baron

Dell #420 (mapback), pb, 1950

Dead of Night. E. P. Dutton, hc, 1950 Unicorn Mystery Book Club, hc,

December 1950. Bound with Wade Miller Murder Charge,

Sturges Mason Schley Dream Sinister

& Richard Sheldon Poor

Prisoner’s Defense

Dell #583 (mapback), pb, 1952

Alibi Baby. Ives Washburn, hc, 1955 Avon #685, pb, 1956

Dead Right. J. B. Lippincott, hc, 1956 Avon #762, pb, 1957, as The Hotel

Murders

Dead to the World. J. B. Lippincott, hc, 1958 Avon #T-320, pb, 1959, as The Blonde in

Suite 14

The Body in the Bed. J. B. Lippincott, hc, 1959 Ace Double D-463, pb, 1960.

Bound with Dying Room Only

(see above).

Dead Certain (Ace Double D-415, pb original, 1960; two novelettes. Bound with Fire on Fear Street (see above). Contents: “Dead Certain” and “A

Grave Matter”

This article and subsequent bibliography (now expanded) previously appeared in Mystery*File 40, December 2003. _____________________________________ YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. Copyright © 2003, 2006 by Steve Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors. Return to the Main Page. |