Wed 28 Mar 2007

by Bill Pronzini

Elliott Chaze (1915-1990) was an old-school newspaperman who began his journalism career with the New Orleans Bureau of the Associated Press shortly before Pearl Harbor, worked for a time for AP’s Denver office after paratrooper service in WW II, and then migrated south to Mississippi where he spent twenty years as reporter and award-winning columnist and ten years as city editor with the Hattiesburg American.

In his spare time he wrote articles and short stories for The New Yorker, Redbook, Collier’s, Cosmopolitan, and other magazines, and all too infrequently, a novel. In an interview he once stated that his motivation in writing fiction, “if there is any discernible, is probably ego and fear of mathematics, with overtones of money. Primarily I have a simple desire to shine my ass — to show off a bit in print.”

His first two novels were literary mainstream. The Stainless Steel Kimono (Simon & Schuster, 1947), a post-war tale about a group of American paratroopers in Japan, was a modest bestseller and an avowed favorite of Ernest Hemingway.

The Golden Tag (Simon & Schuster, 1950), like most of his long works, has a newspaper background, contains a good deal of autobiography, and is both funny and poignant; it concerns a young wire service reporter and would-be novelist in New Orleans who becomes involved with two women, one of them married, while reporting on a sensational murder case.

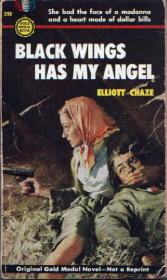

His third novel was the one for which he is best remembered today, Black Wings Has My Angel (Gold Medal, 1953; also published as One for My Money, Berkley, 1962 and as One for the Money, Robert Hale, 1985).

Black Wings Has My Angel is an indisputable noir classic, arguably the best of all the crime novels published by Gold Medal during its glory years. Barry Gifford, in an article in the Oxford American, called it “an astonishingly well written literary novel that just happened to be about (or roundabout) a crime.”

The protagonist, ex-convict Tim Sunblade, is a quintessential antihero — an unrepentant bastard who executes a daring armed car robbery in Colorado with the help of a call girl, Virginia, whom he picked up in a backwoods Mississippi motel.

The details of the crime and its aftermath are vividly described, and the love-hate relationship between Sunblade and the woman and the demons in both that lead to their downfall are masterpieces of dark-side character development. Unreservedly recommended.

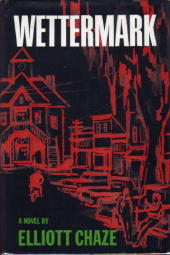

It was ten years before Chaze published another novel, and sixteen years before his next crime novel, Wettermark (Scribners, 1969). In its own quiet, sardonic way, Wettermark is every bit as good as Black Wings Has My Angel. Its setting is the small town of Catherine, Mississippi, a thinly disguised Hattiesburg, where the protagonist, the eponymous Wettermark, toils as a newspaper reporter for the local paper.

Wettermark is a tragicomic figure, accent on the tragic — a tired, financially strapped, ex-alcoholic wage slave whose novelist ambitions have long since been shattered by rejection and apathy. His arrival on the scene of a recent successful bank robbery plants a seed in his mind, a “glimpse of the green” that is nurtured by circumstance and his private demons until it blossoms into a daring heist scheme of his own.

Wettermark is by turns funny, sad, bitter, mordant, and ultimately as dark and unforgiving as Black Wings — a brilliant character study that is likewise unreservedly recommended and that somebody damned well ought to reprint.

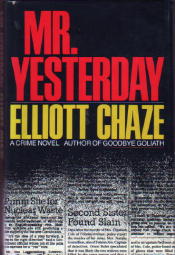

Late in his life, after he had retired from the Hattiesburg American, Chaze wrote three offbeat, ribald (occasionally downright bawdy), and often hilarious mysteries, all published by Scribners, featuring Kiel St. James, a well-meaning but somewhat bumbling city editor for the Catherine Call (Catherine having been mysteriously moved from Mississippi to Alabama for this series); Crystal Bunt, Kiel’s highly sexed young photographer girlfriend; and Chief of Detectives Orson Boles, a tenacious cop given to wearing hideous lizard green polyester suits ( “I like green, hoss”) and speaking alternately in Southern grits-and-gravy dialect and perfect English.

Each of the three, Goodbye, Goliath (1983), Mr. Yesterday (1984) and Little David (1985), drew enthusiastic critical praise — The New Yorker called them “good, down-home fun [with] much flavorful redneck talk…plenty of excitement too” — but they seem to have been inexplicably neglected, if not all but forgotten, in the years since.

The best of the trio is Mr. Yesterday, which deals with the murders of two eccentric old spinsters, one by a fall and one by a bizarre (very bizarre) stabbing. The motive for the two killings, and the method employed in one, are the weirdest, wildest, most inventive, most audacious (and yet completely plausible) ever devised in a mystery novel.

Some readers no doubt did and will find the explanation offensive, even borderline obscene. I laughed out loud when it was revealed, which may tell you more about my sense of humor than you care to know, but I’m pretty sure the author would have approved.

Elliott Chaze was a fine prose stylist, witty, insightful, nostalgic, and irreverent, and a first-class storyteller. If you’ve never read anything of his, or nothing except Black Wings Has My Angel, by all means hunt up copies of Wettermark, Mr. Yesterday, and anything else with his byline. You won’t be disappointed.

April 4th, 2007 at 11:31 am

[…] 4 Apr 2007 Ed Gorman on ELLIOTT CHAZE. Posted by Steve under Authors A day or so after Bill Pronzini’s shortarticle on Elliott Chaze appeared on this blog, Ed Gorman posted the following over on his site. It is reprinted here with his permission: […]

April 14th, 2007 at 10:37 pm

Thank You,Mr.Pronzini! I don’t think i’ve ever,heard of him,now that i have,i will,read all,his books.

April 19th, 2007 at 7:31 pm

[…] I’m sure Bill Pronzini’s recent M*F piece on Elliot Chaze had nothing to do with this. All a big coincidence, no doubt. Riiight … http//www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/content_display/film/news/e3i24b21916578451e52e9d905fd230d4fa […]

October 27th, 2008 at 10:47 am

I was a newbie reporter in the late 60s in Hattiesburg. I wish every reporter had the opportunity to see Elliot Chaze in action. He was outrageous and scarily insightful. Why did you not mention “Tiger in the Honeysuckle,” his best civil rights era novel? Once the world “discovers” Chaze’s work, he may yet be regarded one of the 20th Century’s greatest writers. Of course I’m prejudiced since I knew the “real life” characters in his books.

November 16th, 2008 at 11:24 am

Edd is certainly right that TIGER IN THE HONEYSUCKLE is one of Chaze’s strongest novels; why I failed to include mention of it in my Mystery*File piece I don’t know. But I’ve rectified the oversight in an expanded and revised version called “Paper Chaze”, which serves as an introduction to a Centipede Press reissue of his noir classic, BLACK WINGS HAS MY ANGEL, scheduled for publication shortly. TIGER is mentioned therein as “arguably Chaze’s best noncriminous work of fiction.”

Edd may also be right that he deserves recognition as one of the finest writers of the 20th century; I can only hope it comes to pass. I wish I’d had the pleasure, as Edd had, of knowing Chaze personally. Judging from his work and his irreverent attitude toward any number of subjects, I’m pretty sure I’d have liked him and that we’d have gotten along.

Best,

Bill

March 1st, 2009 at 6:18 pm

Thanks for the article. I picked up a “trashy-looking” book to read last week, Elliot Chaze’s “Love on the Rocks” 1956 printing and was amazed at the quality. From the exploitative blurbs on the back cover I expected much less from it. The blurbs call out some scandalous women which are certainly part of the story, but not at all in the way they’re pitching it. Glad to see my judgement isn’t too far off.

This was a story about a newspaperman working for an AP competitor, set in New Orleans. Not too surprising to see that that’s what he was at one time.

roymeo

September 29th, 2010 at 10:39 pm

Thought some of you might enjoy reading this column by a sportswriter in Jackson, MS.

http://www.hattiesburgamerican.com/article/20071017/LIFESTYLE14/71017015/A-few-words-can-say-so-much

September 30th, 2010 at 10:26 am

Thanks, Edd! Though if there’s a way to access the second page, I’d like to read that too. The link is dead for me.

November 16th, 2010 at 12:55 am

Elliott Chaze was my greatgrandpa. I heard he was a great person. I was born in the year 1997.

December 8th, 2010 at 3:57 pm

Elliott’s daughter Mary, my mother, has never received a dime from her fathers writings. She lives on $1,200.00 a month provided by social security and currently resides in a tiny apartment/public housing. It makes me so warm and fuzzy inside to hear that Ararmath Film Partners are producing their latest project Black Wings Has My Angel with Elijah Wood and Christopher Peditto. It’s good to know that all the wrong people are profiting from my grandfather’s writings. I wonder which one of her greedy siblings is responsible for this act of greed?

June 24th, 2012 at 11:16 pm

Hello,

if anyone in particular interest is reading this right now, don’t stop.

I’m writing now for my grandfather, Melvin Jerry Wade, who is an old friend of Elliot’s son (William) and looking to try and get back in touch. I can’t seem to find a lot of information on the guy but know about his father, Elliot, and his famous writings. He is such an inspiration and hearing my grandfathers story about how he and William met in Fairview, Ok in the year of 1962 was just profoundly amazing. He happened to leave that summer to marry my grandmother then came back that fall to teach (at Fairview) and heard that William had moved to take up another job. He hasn’t seen or heard from him since. This is just a recent hobby of mine. I would like to find out how I can get in touch with William or anyone that could help me help my grandfather. If anyone has any information please don’t hesitate to email me at chelsie.stallings@gallaudet.edu —-I’m always available and will be happy to obtain any new information.

Best regards