AGATHA

CHRISTIE’s Partners in Crime, by Michael Grost

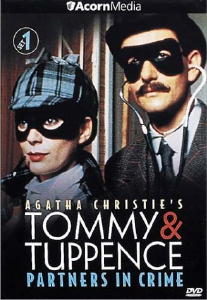

Agatha Christie’s Partners in Crime (Collins, 1929) contains fifteen stories about Tommy and Tuppence, most of them first appearing in magazine form in late 1924. The first two are introductory, the next twelve spoof other detective writers, and the last parodies Christie's own Hercule Poirot. Here are some comments on the tales. FOOTNOTE. “A Fairy in the Flat” (introductory). This story and the next show how Tommy and Tuppence are set up as a detective agency, by the Intelligence chief of Tommy’s. The whole arrangement is similar, in a comic, tongue in cheek way, to that in Herbert Jenkins’ Malcolm Sage, Detective (Jenkins, 1921). Jenkins’ book, like Partners in Crime, is a short story sequence disguised as a novel. In that book the talented Malcolm Sage, former top Intelligence agent in Britain’s Division Z during World War I, is set up in peacetime as a detective by the head of his former department. Sage has a secretary; Tuppence poses as the secretary of their agency, just as Tommy poses as the detective Blunt. Sage has an office boy who reads detective fiction and serves as comic relief; Tommy and Tuppence have Albert, who serves a similar function . Albert seems even younger than Sage’s office boy, however. Both Sage and Tommy and Tuppence are in a typical “modern” office of the 1920’s, with phone lines and buzzers for communication. Tommy and Tuppence are light hearted and playful with this equipment, however, unlike the more serious Sage. Sage can be haughty and turn away customers if he has too much business; Tommy and Tuppence pretend to do the same to make people think they are busy. Everything in Tommy and Tuppence is an exaggerated, parodistic reflection of the set-up in the Sage stories. Sage runs the Malcom Sage Detective Bureau; Tommy and Tuppence the International Detective Agency, whose motto is “Blunt’s Brilliant Detectives.” “A Pot of Tea” (introductory). I like this tale. It is humorous and sweet, and has affinities in its approach to stories in The Listerdale Mystery, such as the title tale and “The Manhood of Edward Robinson,” the latter story appearing immediately after the Partners in Crime stories in the magazines. “The Affair of The Pink Pearl.” Christie does a nice comic job evoking R. Austin Freeman’s Dr. Thorndyke and Polton. She does not get involved in science at all, flatly stating at one point that Tommy and Tuppence (and by extension, their author) know nothing about science, but she does pick up on Freeman’s interest in crafts, the solution turning on her own more domestic version of the same. The young boyfriend who is a Socialist will turn up again in One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (US title, The Patriotic Murders). “The Adventure of The Sinister Stranger.” Well done spy tale; good plot and storytelling, with a nice thread of humor. Christie’s ability to pack such a complex plot into such a small space is impressive. This story spoofs Valentine Williams. “Finessing The King.” Isabel Ostrander was a popular American detective writer of the Post World War I era. She was read by John Dickson Carr as a teenager, according to Douglas G. Greene’s biography, was praised by Dorothy L. Sayers in The Omnibus of Crime and The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, and was one of the famous detective writers chosen for parody by Agatha Christie here. Despite this one time fame, her works are almost completely forgotten and unobtainable today. This story spoofs Ostrander’s series detective, ex-cop Tommy McCarty, and his best friend, fireman Dennis Riordan. Tommy dresses up like a fireman at a costume party, a favorite Christie setting, while Tuppence masquerades as McCarty. As does McCarty in Ostrander’s The Clue in the Air, Tommy and Tuppence hear the murder committed, and are the first to find the body. In both stories the victim is a young society woman. They also hear the victim’s dying message, just as in Ostrander’s novel. Christie’s construction of a plot around the “dying message” situation is superb. “The Case of the Missing Lady.” This is a dynamic spoof of Conan Doyle’s “The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax.” The burlesque is done more through Christie’s brilliant plotting than through stylistic means. It is the cleverest story in the book. Earlier, Christie’s Poirot story “The Veiled Lady” also was constructed as an ingenious takeoff on a Doyle story, “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton.” This earlier story is less of a parody than “Lady,” but it still centers around a twist on the master. “Blindman’s Buff.” Parody of the Thornley Colton stories by Clinton H. Stagg. Christie’s spoof of Stagg’s mannerisms is very funny. Christie’s parody can be classified as a burlesque; it uses slapstick and other low comedy elements. She picks up on the absurdities of his assistant Sydney Thames, so named because he was found as an orphan near that river, and the “Keyboard of Silence.” She also uses the restaurant setting that opens Stagg’s story. Stagg’s work consists of fair play puzzle plots; Christie’s little spoof is a thriller, and confines its parody to his detective characters; it does not seem to take off on Stagg’s detection or plotting techniques, unlike her spoofs of Chesterton or Orczy, for example.  “The Man in the Mist.” The Chesterton takeoff. There is well done atmosphere in the first half of the tale, not quite Chesterton-like, but close enough, and good in its own right. Christie is also sharp about the use of color in Chesterton’s scene painting. Christie has also got one of Chesterton’s poets in the tale. The solution of the story as a mystery is much more ordinary; it draws on one of Chesterton’s most famous tales, but does not augment it. Still, this is a good story. “The Crackler.” Even the title of this tale sounds like one of Edgar Wallace’s series characters. There is some good natured ribbing of Wallace in the early pages. Christie sets the story in the Wallace turf of high living cafe society characters who are also crooks. The finale involves a Biter Bit, a common Wallace plot approach. As a mystery plot, the tale is pretty weak. “The Sunningdale Mystery.” An astonishing pastiche of the Old Man in the Corner tales by Baroness Orczy. Very close in every way to the originals. Christie has not only caught Orczy’s stylistic mannerisms, she is also on to the Baroness’ plotting style. Some of the Orczy like characteristics: There is the emphasis on the movement of people around, during a situation involving the last people to see the victim alive. There is the element of financial crookedness in the background of the story. Most importantly there is the way that the various plot elements of the story do not add up to a consistent, coherent picture at first glance. There are many contradictory indications, and the plot as a whole just does not make sense. It is up to the detectives to provide new perspectives, a new way of looking at things, to make the events of the crime at all understandable, and eventually completely logical. This is the essential plotting style of the Old Man stories to a T. Christie’s ingenious solution to the mystery also recalls Orczy’s ingenious twist answers. In 1931 Christie contributed two chapters to the Detection Club round robin novel The Scoop. The most personal thing of Christie’s is Chapter 4. In this section, a young crime reporter and his girl friend come together at a restaurant to discuss the case and analyze the mystery. Their egalitarian relationship and analytical insight recall Tommy and Tuppence, especially the story “The Sunningdale Mystery,” which involves the couple solving a crime by discussing it in an ABC teashop. Just as in Partners, each builds on the other’s ideas, and there is no sign of sexism, just mutual respect and intellectual equality. There is also a sense of light-hearted fun and romance. “The House of Lurking Death.” Christie picks up on the morbid atmosphere of horror, menace, and psychological abnormality in such A.E.W. Mason works as The House of the Arrow. Everybody likes Mason but me. This story is one of a series Christie wrote about ingenious poisonings. They include “The Coming of Mr. Quin,” from The Mysterious Mr. Quin; “The Tuesday Night Club,” the first tale in The Thirteen Problems; “How Does Your Garden Grow?” from The Regatta Mystery; and Sad Cypress. All of these stories’ solutions contain features in common, and also new ingenious variations. “The Unbreakable Alibi” takes off on Freeman Wills Crofts’ alibi stories. The tale disappoints: Christie creates an interesting “impossible to break” alibi, and then resolves it through a spoof solution that would be considered cheating in a non-humorous mystery. I was hoping for one of Christie’s brilliant plot devices... Tuppence points this out herself at the end of the story. Christie occasionally wrote straight detective stories in the Crofts tradition, such as “The Sign in the Sky” from The Mysterious Mr. Quin. “The Unbreakable Alibi” appeared in 1928, four years after most of the other tales were published. “The Clergyman’s Daughter.” This is a routine hidden treasure story. A million kid’s mystery novels have since been cast in this same mode. Christie’s interest in mysteries centered around household economy will later find fulfillment in “How Does Your Garden Grow?”. Christie makes this story be a spoof of Anthony Berkeley’s detective Roger Sherringham, but its plot seems closest to H.C. Bailey’s “The Violet Farm.” “The Ambassador’s Boots.” Christie has noticed H.C. Bailey’s way of having his stories start with small little unexplainable incidents, whose investigations gradually uncover grandiose and sinister conspiracies. This was one of the best episodes of the 1980s British TV series. “The Man Who Was No. 16.” This story spoofs Christie’s own The Big Four. This is a story sequence that Christie later “fixed-up” to look like a novel. The stories appeared during the first half of 1924, just a few months before the stories in Partners in Crime. The Big Four is one of Christie’s weakest works. The only story widely reprinted from it is “A Game of Chess.” That story turns on a mechanical murder device, reminiscent of the Coles, or Ernest Bramah. Christie would create another murder device in “The Face of Helen”(from The Mysterious Mr. Quin, one that recalls not just the Coles, but Richard Marsh’s The Beetle. This 1923-1926 flirtation with the scientific murder story was just a passing phase in Christie’s work. It looks as if, for a time, Christie was considering joining the Freeman school, then at the height of its prestige in British crime fiction. One can see its traces in such scientifically based Poirot Investigates, in stories as “The Tragedy at Marsden Manor,” and “The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb.” In the first of these stories, Poirot is even brought in by the insurance company to investigate, just like Dr. Thorndyke. The latter also has the Egyptology background beloved by Freeman. The use of hypnotism to bring to light “hidden memories” of witnesses by Poirot in “The Underdog” also belongs here. Christie was perhaps the first to use such a device in fiction. Even the doctor narrator of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd might reflect Freeman’s doctor narrators. (There – I’ve managed to say something original about Roger Ackroyd.) Christie would soon revert to “herself,” and abandon the Freeman school. A lifelong interest in poisons would remain, but one involving highly ingenious puzzle plots, not purely scientific methodologies. Also, Christie’s interest in Egypt would grow from a fashionable fad to a deep personal involvement in the archaeology of the Middle East. Getting back to “The Man Who Was No. 16,” this tale has plot elements in common with the later “Miss Marple Tells a Story.” Both deal with the intricacies of hotel room floor plans. Both works have links to the impossible crime tradition. “The Man Who Was No. 16” also recalls an era when both the police and the bad guys could afford an unlimited number of agents to go undercover in an immense variety of roles. One sees similar effects in Frederick Irving Anderson’s The Book of Murder and Erle Stanley Gardner’s Lester Leith tale “The Bird in the Hand.” Mainly, this tale is an exuberant addition to Christie’s spy fiction, one of the more underrated sides of her work. Plot elements in it anticipate Christie’s masterpiece in the spy genre, They Came to Baghdad. Partners in Crime is not the only Christie work of the mid twenties to spoof detective stories. The more serious in tone tale “The Love Detectives,” from The Mousetrap, also undercuts detective fiction conventions, as does The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Christie’s mystery reading as a whole is somewhat mysterious. In addition to the authors cited in Partners in Crime, her autobiography records inspiration from Anna Katherine Green and Gaston Leroux; she refers to writings by Maurice Leblanc in “Strange Jest,” and Mary Elizabeth Braddon in “Greenshaw’s Folly”; she gave blurbs to Allingham, Bentley, Carr, Elizabeth Daly and praised Rex Stout in an interview (especially Too Many Cooks); and served on a jury that gave a prize to John Sladek’s “By an Unknown Hand.” Ragnar Jonasson, who translated The Body in the Library into Icelandic, has pointed out a witty passage in Chapter 8, where a boy has collected autographs from Dorothy L. Sayers, Christie herself, John Dickson Carr, and H.C. Bailey. This seems to be Christie’s homage to her fellow Detection Club members. Both The Clocks and Partners in Crime refer to G.K. Chesterton, and it is tempting to see him as a major love of Christie’s. We know from Christie’s letters that she read S.S. Van Dine. The opening chapter of Mrs. McGinty’s Dead offers Poirot’s negative impressions of what we now know as film noir. At one time Christie considered adapting Dickens’ Bleak House to the screen, but gave up because the book was too complex to allow condensation without artistic damage. Christie’s reading in the mystery genre was certainly broad, and she was clearly familiar with the history of the genre, although she rarely wrote about it, unlike many of her other colleagues. Christie’s favorite characters were the Watsons. She regarded Dr. Watson as Conan Doyle’s greatest creation (see The Clocks), and she singled out Archie Goodwin for special praise in her interview about Rex Stout (quoted in his biography by John McAleer). Oddly, her own Watson, Captain Hastings, is one of her least successful characters. Maybe she was impressed with other authors’ Watsons because she knew from experience how hard they were to create. All of the stories in Partners in Crime are explicitly comic, and are crosses between the humorous tale and the mystery story. Actually, most of Christie’s works have large elements of comedy in them. Her books are extremely funny, and often gentle spoofs of their characters and their social milieu. FOOTNOTE. In Crime Fiction IV, Allen J. Hubin lists seventeen stories. “Finessing the King” / “The Gentleman Dressed in Newspaper” is one short story. It is just broken up into two sections with different titles. I simply called it “Finessing the King” in my article. Similarly, “The Clergyman's Daughter” / “The Red House” is one short story. Thus there are really only fifteen. Mike Grost is the author of A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection, from which this article has been revised, and the Jacob Black “Impossible Crime” mystery short stories.  Agatha Christie’s Partners in Crime - Tommy & Tuppence. British TV series, ITV1, 1983-84. Cast: Francesca Annis (Tuppence Beresford), James Warwick (Tommy Beresford), Reece Dinsdale (Albert), Arthur Cox (Detective Inspector Marriott). Available on DVD: * = Set 1; ** = Set 2.

This article and other material also appeared in Mystery*File 45, August

2004.

_____________________________________ YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. Copyright © 2004,2006 by Steve Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors. Return to the Main Page. |