|

STEPHEN GREENLEAF: CREATOR

OF

CALIFORNIA’S NEXT GREAT PRIVATE EYE - by Ed Lynskey

Upon Kenneth Millar’s death from Alzheimer’s in 1983, a worthy successor to his PI Lew Archer had already been established. The first of Stephen Greenleaf’s PI John Marshall “Marsh” Tanner’s novels, set in San Francisco, had debuted in 1979. This new private eye’s name derived from John Marshall, America’s first Chief Justice, and Greenleaf’s former basketball coach, a man named Tanner. Like Greenleaf, Tanner was also a lawyer and a member of the California bar. Clocking in at fourteen novels published from 1979 to 2000, the PI Tanner series enjoyed a solid, if not spectacular, run of critically well-received entries. Though the Tanner books didn’t grab big commercial pots, devoted mystery fans hold them in exceptionally high regard.  The initial Tanner title, Grave Error (1979), opens with this simple, elegant

sentence: “Clients come and go.” The book is dedicated to the

author’s wife, Ann (as is the series’ final title, Ellipsis). Tanner’s wry, dry humor surfaces

in an early scene: “Minutes

rolled by like the closing credits of Stars Wars. I yawned.

Andrea typed. The world turned.” Tanner has his

quirks. He owns a Paul Klee original and works at his

grandfather’s desk. His Della Street, Peggy Nettleton, a

key player throughout the early books, is introduced.

The initial Tanner title, Grave Error (1979), opens with this simple, elegant

sentence: “Clients come and go.” The book is dedicated to the

author’s wife, Ann (as is the series’ final title, Ellipsis). Tanner’s wry, dry humor surfaces

in an early scene: “Minutes

rolled by like the closing credits of Stars Wars. I yawned.

Andrea typed. The world turned.” Tanner has his

quirks. He owns a Paul Klee original and works at his

grandfather’s desk. His Della Street, Peggy Nettleton, a

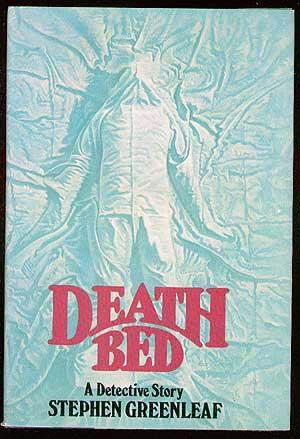

key player throughout the early books, is introduced.Tanner is hired by the wife of Roland Nelson, chief of a corporate watchdog institute, to investigate for running up huge, suspicious expenses. Coincidentally, the Nelsons have an adopted daughter, Claire. She has retained Tanner’s old PI mentor, Harry Spring, to root out answers about her troubling origins. Throw in Sara Brooke, an attractive assistant at the institute, and all the elements to a complex, twisty plot are assembled. Spring then turns up slain in the odd-sounding town of Oxtail. His wife, Ruthie Spring, engages Tanner to nail the killer. Ruthie, the profane yet lovable Texas cowgirl, will become a series mainstay as Tanner’s pal. Greenleaf quickly established himself as a writer of literate detective novels – all done over the transom without the benefit of a literary agent. Articulate, mature, and stylish, Grave Error numbers among the best first PI novels I’ve read. Grave Error garnered the gushy reviews every neophyte novelist craves. Most notably, The New Yorker raved, “The classic California private-eye novel . . . Mr. Greenleaf is a real writer with a real talent.” “From the very first sentences readers will know they’re in very good hands,” remarked The Washington Post. The second Tanner yarn, Death Bed (1980), is how I backed into the series. Max Kottle, an affluent San Franciscan businessman dying of cancer, retains Tanner to hunt up his son, Karl, 30, and ten years estranged. This plot fits the classic Ross MacDonald-Lew Archer template (PI tangles with rich, dysfunctional family). Charley Sleet, Tanner’s cop pal, helps out on cases with his police smarts and resources. Tanner romances Pamela Brown, “girl-reporter”. Tanner here views himself as “a nondescript private eye who could stuff all of his assets into some carry-on luggage if he owned any carry-on luggage.” Apt metaphors and similes glimmer in the narrative: “The bay lapped like a wolfhound at the shore below, the sound dissonant with the mindless roar of the commuters on the freeway above.” For my money, Death Bed is the standout in the first wave of Tanner sagas. Vivid descriptions of urban San Francisco crackle. The dialogue feels honed pitch perfect. Tanner as a character develops his own idiosyncratic moods and such personality traits like munching on Oreos while drinking Scotch. Critics reacted positively. The New Republic (a “literary” venue) wrote, “This is what a good mystery is all about.” New York Magazine cited the novel’s strengths as “intellectual deduction and good guesses, wit and cynicism.” Death Bed also snagged a review in 1001 Midnights, the seminal guidebook to crime fiction. Greenleaf’s third detective novel, State’s Evidence (1982), has to win the most attractive dustjacket cover design (done by  artist Gary Cooley). To help locate Teresa Blair, a model and a

witness in their case against Tony Fluto, a local Mob boss, the

DA’s office hires Tanner. It marks one of the rare times he

helps the cops. Among those knowing Teresa are her cold fish

husband James and a floozy society lady friend Tancy Verritt.

artist Gary Cooley). To help locate Teresa Blair, a model and a

witness in their case against Tony Fluto, a local Mob boss, the

DA’s office hires Tanner. It marks one of the rare times he

helps the cops. Among those knowing Teresa are her cold fish

husband James and a floozy society lady friend Tancy Verritt.This edgy, loopy plot literally runs Tanner in circles. His self-effacing wit remains intact. While at the swanky tennis club he observes a scene: “He [the tennis pro] called the woman Mimzy. I looked around for Scott Fitzgerald and John O’Hara.” Tanner also proves all too mortal when Tancy seduces him for a zesty romp in the sack. The most intriguing, surprising scenes occur inside the courtroom once Teresa is found to give testimony. The tender portions in State’s Evidence are those scenes where Tanner glues back together fractured families, most notably at the novel’s end. Greenleaf demonstrates his ease at orchestrating a courtroom drama, and a fuller shading of Tanner’s personality emerges. The New Yorker concluded that State’s Evidence put Stephen Greenleaf on the private eye map: “He has embellished the form with his own style, his own imaginative perspective, his own distinctive grasp of character.” Fourth in the series was Fatal Obsession (1983). The first of the Tanner out-of-town capers, the private eye is summoned back to his native Chaldea, Iowa. A family crisis looms over just how to dispose of their ancestral farm. Two brothers (who are markedly different from Tanner) urge selling it. Meantime, a sister lobbies to retain the land for her daughter to work. Meantime, Billy, a black sheep nephew is found hanged. Local law enforcement rules it a suicide. Tanner has other ideas. His disturbing Vietnam memories play a pivotal role in the mystery’s resolution. Greenleaf handles the agrarian setting and cast of supporting characters with proficient skill. Living in Iowa and attending the Iowa Writers Workshop no doubt aided him. The title also makes for a refreshing diversion from foggy, moody San Francisco. Ringing endorsements abounded. Playboy touted Fatal Obsession by saying, “Greenleaf gives the genre new life and richness.” New York Times Book Review continued to compare Greenleaf to past masters: “Mr. Greenleaf is a superior writer. He also has compassion, and his books are being talked about in terms of Hammett and Chandler.” Fatal Obsession also made it onto critic Robin W. Winks’ “A Personal List of Favorites.” Book number five, Beyond Blame, came out in 1986. The premise behind this Tanner vehicle is an intriguing one. Berkeley law professor Lawrence Usser is an expert in temporary insanity defenses. When he’s arrested for the savage murder his wife Dianne, her family hires Tanner to gather evidence to prove Usser is sane in an attempt to head off his possible insanity plea.  During the investigation, Tanner

finds Lisa,

Ussers’ runaway daughter living on the mean streets. The

actions of the grungy street kids and the slick lawyers/psychiatrists

play off each other. Who is, you have to wonder, the less

human? Lisa seeks refuge in her psychotic boyfriend dubbing

himself Maniac. Tanner, always the calm eye to the storm, strives

to rescue her. His holding things together is what continued to

fascinate me in an intricate, engrossing plot. During the investigation, Tanner

finds Lisa,

Ussers’ runaway daughter living on the mean streets. The

actions of the grungy street kids and the slick lawyers/psychiatrists

play off each other. Who is, you have to wonder, the less

human? Lisa seeks refuge in her psychotic boyfriend dubbing

himself Maniac. Tanner, always the calm eye to the storm, strives

to rescue her. His holding things together is what continued to

fascinate me in an intricate, engrossing plot. Newsweek summed up this exceptional novel as follows: “Readers who like their private eye novels witty, literate, and properly balanced between misanthropy and compassion will find Stephen Greenleaf’s Beyond Blame exactly to taste.” Publishers Weekly also pointed out Greenleaf’s “superior literary skills,” by now an opinion shared among critics. 1987 saw the publication of Toll Call, number six for Tanner. This is one of the most poignant, haunting titles of the oeuvre. Peggy Nettleton, Tanner’s able secretary-confidante for eight years, is the victim of obscene phone calls. Tanner says, “Peggy’s gritty self-reliance could make Pete Rose look like a shirker.” Even so, she falls psychological victim to her online Svengali. At one point, serving as bait in a public park to nab the caller, she performs “a vile striptease.” On this visceral level, the novel skirts close to a psychological thriller. However, Peggy’s tormentor seems more cerebral than most stalkers, offering an explanation for his perversion: “Sex is a foreign language to me, its energies and excitements as unfamiliar as Sanskrit ... So I came to you for help. I selected you to teach me what I had to know.” Once Peggy’s phone caller has been silenced, a second larger mystery involves the abduction of Peggy’s friend’s small daughter. After a violent confrontation with the culprit, it is Peggy who comes to Tanner’s rescue, but the painful upshot to this double ordeal is her resignation. Heartsick, Tanner feels cut adrift by the novel’s end. Only Ruthie Spring and Charley Sleet continue to stick by him. Typical of the critical reception was the San Diego Union’s on the dustjacket blurb: “Stephen Greenleaf’s John Marshall Tanner series improves with age. Tanner [is] ... altogether one of the most convincing of today’s private eyes.” Number seven in the series was Book Case, which appeared in 1991. This is a first-rate biblio-mystery. Tanner’s client this time is Byrce Chatterton who runs Periwinkle Press, a regional press financed by his wealthy wife Margret. A manuscript entitled Homage to Hammurabi arrives at their offices, “a thinly disguised expose that will blow the lid off some of Cow Hill’s sexiest secrets,” and it is a veritable blockbuster. PI Tanner’s quest is to track down the anonymous author. Excerpts from Hammurabi prefacing each chapter also tell a story as Tanner’s search takes him into darker crimes. This time it’s a fabricated rape charge and subsequent false imprisonment. At this point in his life, Tanner is reading Richard Russo, listens to KJAZ, and is dating Betty Fontaine, a high school teacher. Charley Sleet continues to lend a hand. An interesting side drama has Tanner with writer aspirations, abandoning his manuscript about this case on page 82. Book Case was nominated for a 1992 Dilys Award. The novel collected solid comments such as “twisty and absorbing” from Kirkus Reviews and “moving, riveting, and appropriately bookish” from The Boston Globe. Book number eight was Blood Type (1992). This book’s social topic, the nation’s blood supply, struck a personal chord for me. Working for the American Red Cross a decade later, I still heard the same horror stories about the bad blood. Tanner’s drinking pal, Tom Crandall, “a vat of contradictions,” hires the PI to help block his singer-wife Clarissa Duncan from leaving him to marry Richard Sands, “a San Francisco titan” of Sandstone Enterprises. Predictably enough, Crandall turns up dead. The conclusion of the cops is that it was a suicide. Tanner dissents. Tainted blood and falsified research data from a fly-by-night outfit called Healthways attract his attention. One of the novel’s strengths is the blood science that is clearly explained in laymen’s terms. There is also a chase, as Tanner pursues Tom’s paranoid brother Nick through the inner city sleaze and non-atmospheric San Francisco looking for answers. Besides the personal association mentioned, I enjoyed Blood Type for its more gritty, hard-boiled tone. Library Journal summarized other reasons: “tough, meaty prose, sly twists in plot, and immediacy of action.” Similarly, Booklist wrote, “An excellent mix of technical detail and low-life grunge.” The other book trade journal, Publishers Weekly assessed it as “chilling.” Book nine, Southern Cross (1993), is a real gem. On his second trip away from SF, Tanner goes to a twenty-fifth year reunion at his Midwest college. He meets up with an old friend, Seth Hartman. Troubles in Charleston, South Carolina disturb Seth, and Tanner accompanies him home. A white supremacist group, Alliance for Southern Pride, has been harassing Seth, a liberal lawyer. One of his clients, Alameda Smallings, is a black girl, the first seeking admittance to the Palisade, an all-white military academy. All the old skeletons from the Civil Rights days are dragged out for kicking around, but in this book they make new, relevant noises. By the end, Tanner describes his case as “the old days crawled out from under a rock and sort of made a mess of things.” Southern Cross, arguably the best plotted of Greenleaf’s mysteries, sweats with local color but also maintains a breezy pace. Minor characters receive a full-fledged treatment, especially the numbing portrayal of the white separatists. The tireless, tenacious Tanner does a nifty turn of detective work to root out the surprising solution. Typical of the critics’ positive reactions was Publishers Weekly, noting the novel “shows off the witty and trenchant Greenleaf in fine form” as well as his “gallery of intriguing characters.” For Tanner’s tenth outing, False Conception (1994), Greenleaf presents Tanner’s deepest social conscience in the knotty issues arising from surrogate parenthood. This time there is no murder falling into Tanner’s lap. Instead, affluent Stuart and Millicent Colbert hire him to run a background check on Greta Hammond, a prospective surrogate mother. Greta and Tanner have sex, which is integral to the book’s outcome. Once impregnated however, Greta bolts for parts unknown. Tanner sets out to find her. Again, echoes of Ross Macdonald and Lew Archer are heard. The rich do live different up in St. Francis Wood. Brother Stuart (Women’s Wear) and Sister Cynthia (Men’s Wear) vie to inherit a fashion empire from Rutherford Colbert, their old, decrepit, and autocratic father. Meantime, Tanner breaks up with his on-again, off-again girlfriend, Betty Fontaine. He comments, “When a relationship breaks and you are the breakee and not the breaker, a portion of the bond remains long after the termination has been announced.” Consolation is his unwittingly fathering the Colbert’s new daughter, Eleanor. Tanner has become a dad, of sorts. Critics lauded False Conception. New York Times Book Review asserted, “Mr. Greenleaf writes like a literary guerilla. Lulling his readers by laying out the messy moral questions with clarity and intelligence.” San Francisco Chronicle (also Tanner’s favorite newspaper) pointed out that “Greenleaf’s portrayal of the wealthy Colbert family’s misguided efforts to insulate itself from the consequences of prior mistakes is unerring.” Publishers Weekly characterized Tanner as a “thoughtful and engaging protagonist.” Booklist wrote: “Tanner novels are never just mysteries; Greenleaf always weaves in a larger human dilemma, and here he does it more successfully than ever before.” Finally, the venerable Virginia Quarterly Review commented on “a plot so intricate that it would make Ross Macdonald proud.” Eleventh in the Tanner sequence, Flesh Wounds (1995), lures the PI for a third time out of San Francisco to cold, wet Seattle. This time he runs to the requested aid of his old secretary Peggy Nettleton, six years out of his life with little communication. He  bundles with him those old feelings of

romance

for her. Alas, it goes largely unrequited. Peggy wants to

wed rich businessman, Ted Evans. However, Ted’s daughter

Nina by a former marriage is missing. Ted can’t tie the

knot until Nina is found safe. Peggy is distraught. Tanner

understands his assignment but not with much relish. bundles with him those old feelings of

romance

for her. Alas, it goes largely unrequited. Peggy wants to

wed rich businessman, Ted Evans. However, Ted’s daughter

Nina by a former marriage is missing. Ted can’t tie the

knot until Nina is found safe. Peggy is distraught. Tanner

understands his assignment but not with much relish.Using an artful (and successful) structure, Greenleaf alternates third-person Nina and first-person Tanner POVs to spin out the yarn. Nina has disappeared into Seattle’s seedy underworld of pornography, what she believes is erotic art. Greenleaf’s descriptions of Seattle are precise. The then-new concept of virtual reality imperils Tanner in one hairy, unique scene. Tanner, away from his sidekicks Ruthie Spring and Charley Sleet, does okay on his own. Without them, he carries the brunt of the story, a chance to open up more to readers. At the end, our knight-errant returns to San Francisco, unhappy but wiser. Flesh Wounds scored high with book reviewers. Publishers Weekly commented how Tanner’s “ruminations on the power of money, sex, and security give rich character to an absorbing tale.” New York Times Book Review rated it as “a first-class noir.” Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine praised Greenleaf’s “crisp prose.” Chicago Tribune gave it a thumbs up, saying “Better yet are the characters that Tanner meets on his journey around Seattle, all of them sharply drawn and believable.” San Francisco Chronicle said, “Greenleaf’s use of such issues as the misuse of technology, voyeurism, and repressed sexuality places him high among the ranks of detective-story writers.” Flesh Wounds was also nominated for a 1997 Shamus Award for Best Hardcover Private Eye Novel. At an even dozen books, Tanner’s tale in Past Tense (1997) turns raw and tragic. In short, Tanner is forced to go on the hunt after his cop pal, Charley Sleet, who has unaccountably killed a defendant in an open courtroom. The rapid deterioration of Sleet’s sterling character is the book’s dramatic axis. Confused yet still loyal, Tanner tries to outwit Sleet, whom he acknowledges as his superior in evasion and in every aspect of police work. Incest and dirty cops seem to be at the center of the mystery. While an engrossing read throughout, I also did not want Charley Sleet's story to end badly. As always, Tanner keeps his chin up. Sleet’s reasons, once exposed, are understandable and believable, but the ending remains very much a shocker.  Past Tense fared well with most critics. The Washington Post rightfully concluded it was “unforgettable.” Library Journal judged Tanner as “moody, witty, and appealing” and the book as “moving and full of valuable insights.” Boston Globe said, “Past Tense sets out textbook examples of how to hook the reader.” Publishers Weekly liked the “compelling climax.” New York Times Book Review referred to Tanner as the “conscientious San Francisco investigator.” Usually unlucky number thirteen in the Tanner books, Strawberry Fields (1999), finally snared Greenleaf an overdue, well-deserved Edgar Award nomination for Best Book. Tanner, in the hospital recuperating from a serious gunshot wound (from the incident that came at the end of Past Tense), befriends Rita Lombardi. She’s on the same floor for surgery on a disfigured foot. Once home, after they’re both discharged, Tanner learns that Rita has been stabbed to death. He drives down to Haciendas, her hometown in the Salinas Valley where strawberries are the king crop. Tanner’s investigation begins with Rita’s laconic lover, Carlos. Besides the first-rate, intricate detective yarn, Greenleaf paints a stark, stunning setting which he shows is a living hell for migrant farm workers. Grim details abound about their tragic plight in the post-Chavez era. A tangible cynicism permeates this narrative. At one point, Tanner comments, “HARD COPY and O. J. have eroded our moral fabric. Truth and justice go to the highest bidder – unless it’s bought and broadcast, it isn’t real.” Though Charley Sleet is now gone, Ruthie Spring (still calling Tanner “Sugar Bear”) helps out. One can see why he also strikes up a romance with Jill Coppelia, a modern lady lawyer and Assistant DA. This one looks to be the real deal for Tanner. She’s investigating the Triad, the corrupt cop gang Charley Sleet sought to topple in Past Tense. This time around we see that Tanner reads Ross Thomas, drives a Buick, and watches THE X-FILES. Critics hailed this penultimate Tanner project with characteristic warmth and enthusiasm. The book trade journals weighed in, with Publishers Weekly noting the “complex, absorbing plot,” and Library Journal the “sound plotting and meaty prose.” New York Times Book Review wrote “A scorching case against a feudal business that keeps its workers in virtual slavery.” Kirkus Reviews said the book would “make you cringe with guilt next time you bite into a non-union picked strawberry.” J. Kingston Pierce for January Magazine wrote: “Yet it is pleasing to see that a classic, dogged investigator like Marsh Tanner can still appeal in a genre filled with gimmicky sleuths. Measured by his efforts, he stands tall.” Finally, fellow crime writer Andrew Vachss hailed Greenleaf as “one of Chandler's rightful heirs.” Finally, now in his fourth decade, PI Tanner took his final bow with Ellipsis (2000). Chandelier Wells, a mega-selling romance novelist, hires Tanner for bodyguard duties, admittedly a strange gig for a PI. On the other hand, it pays the bills. Tanner goes through the motions until a car bomb explodes. His prickly client, the intended target, isn’t blown to bits. The investigation shifts into high gear. Along the way he manages to get the remnants of the Triad arrested, perhaps putting to rest his demons over the late Charley Sleet. One bomb-making suspect is an unsuccessful (but memorable) romance author who accuses Tanner’s client of plagiarism. The novel climaxes in sentimental yet appropriate fashion with Tanner’s fiftieth birthday party. His old friends and associates, including Peggy, show up to wish him well. Pearl Gibson, a neighbor lady who has recently died, leaves Tanner with a life-changing gift. Jill Coppelia has quit her DA job and marriage lurks in the wings. The sense of closure given in this last book is a rare one to be found in private eye series. (Bart Spicer’s Exit, Running, which has PI Carney Wilde say good-bye, is one other series that comes to mind.) Critics dealt Private Eye Tanner a rousing sendoff. Library Journal thought the book was “entertaining” and “Greenleaf’s prose and repartee could not be better.” Publishers Weekly remarked how “the plot has an irresistible momentum, and Tanner’s emotional evolution continues to fascinate.” Marilyn Stasio for New York Times Book Review pointed out, “But for the most part, Greenleaf has fun picking apart the seamier aspects of the book trade,” and “it’s all Tanner can do to keep a straight face.” Ellipsis was nominated for a 2001 Shamus Award for Best Hardcover Private Eye Novel. On balance, the PI John Marshall Tanner books can hold their own when stacked up against contemporary sleuthing series. The moody, witty, and intelligent Tanner maintains a consistent personality even as his personal life drifts toward the stable, happier plateau of his middle years. Certainly, if Mr. Tanner should elect to come out of retirement at age 50, he’d be relatively young in the modern PI trade. One sees the Nameless Detective and Dan Fortune still at work through their golden years, for instance. A solid argument can also be made for tracing the traditional PI subgenre’s development through the lineage of Hammett, Chandler, Macdonald – and finally Stephen Greenleaf. Suggested resources: Contemporary Authors: New Revision Series, Volume 95. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998. Chastain, Thomas. “Interview with Stephen Greenleaf.” Armchair Detective: A Quarterly Journal Devoted to the Appreciation of Mystery. Vol. 15, No. 4. 1982. Greenleaf, Stephen. “The John Marshall Tanner Novels.” Mystery Readers International Journal, San Francisco Mysteries Issue. Volume 11, No. 2. Summer 1995. “John Marshall Tanner.” The Thrilling Detective web site. http://www.thrillingdetective.com/tanner_jm.html Muller, Marcia, and Bill Pronzini, editors. 1001 Midnights: The Aficionado’s Guide to Mystery and Detective Fiction. New York: Arbor House, 1986. Murphy, Stephen M., editor. Their Word is Law: Bestselling Lawyer-Novelists Talk About Their Craft. New York: Berkeley Books, 2002. Robinson, Marlyn. “Collins to Grisham: A Brief History of the Legal Thriller.” Legal Studies Forum 21 (1998). http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/lpop/legstud.html. Sallis, James. “Ghost of a Flea.” The New York Times, December 31, 2001. Mentions Stephen Greenleaf as an early influence to his own crime fiction. Sheppard, R. Z. “Neither Tarnished Nor Afraid: Hard-Boiled Fiction Continues to Influence and Entertain.” Time Magazine. June 16, 1986. A good perspective on PIs and hardboiled lit. in general. Stasio, Marilyn. “Ellipsis.” The New York Times Book Review. July 23, 2000. VII 202. Vachss, Andrew. “Righteous Reading.” http://www.vachss.com/media/righteous. Winks, Robin W. “A Personal List of Favorites.” Detective Fiction, A Collection of Critical Essays. Woodstock, VT: Countryman Press, 1988. INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN GREENLEAF - Conducted by Ed Lynskey Introduction: In preparation for my email interview with Stephen Greenleaf, I read the corpus of fourteen PI John Marshall Tanner novels. After the interview questions had been drafted, the back-and-forth exchange of emails resulted in the interview completed on April 27, 2005. Thanks to Steve Lewis for helping to formulate some of the questions below. Q. You’ve had a long, successful run in the PI John Marshall Tanner series (14 books) similar to Bill Pronzini’s “Nameless Detective” and Robert B. Parker’s Spenser. How does an author infuse enough power and interest in a series character to keep him going? Tanner grows in the series as he moves into middle age. Did his journey of personal discovery parallel the cases he undertook? A. In the beginning, I felt that in order to remain vital, the Tanner books should be more about the people and places he encountered along the way than about the detective himself. I agreed with Ross Macdonald that the detective was essentially a lens through which the world at large was observed. To that end, I minimized Tanner’s biography in the first three books. Only in Fatal Obsession, when he returned to his home town and become embroiled in the murder of his nephew, did his backstory become more fully fleshed out. Tanner did change with age, though in my view not dramatically. My view is not authoritative, however. Since Tanner is essentially me inthe third draft, and since I am not fully aware of how my own ebb and flow inevitably created changes in him, it falls to others to best describe that arc. I do think over the years Tanner became more sympathetic and less judgmental, less of a show-off and more of a grown-up, less idealistic and more tolerant. He also sired a child and fell in love. But most of the growth was triggered by age. In the beginning, Tanner was older than I was and by the end he was younger. When our demographic paths began to cross, and I knew exactly how it felt to near fifty, he began to be visited by some of the ailments I was dealing with, most notably depression, to some readers’ disgust, I might add. Tanner emerged from his depression more or less intact, as did I, but I do think age, more than the sort of cases he took on, was the predominant influence on his inner life, at least toward the end of the series.  Q. Did

your own life experiences such as serving in Viet Nam and

working as a lawyer influence the genesis of Tanner as a series

protagonist? For instance, we know that Marsh is a

lawyer-turned-private detective. Are there any similarities here,

or anywhere else, with your own life? Q. Did

your own life experiences such as serving in Viet Nam and

working as a lawyer influence the genesis of Tanner as a series

protagonist? For instance, we know that Marsh is a

lawyer-turned-private detective. Are there any similarities here,

or anywhere else, with your own life?A. As with most writers, my life experience provided a foundation, though not an exact template, for my work. Tanner’s background, and my own, is the reason contemporary legal issues appear in the books with some frequency (e.g., repressed memory of childhood sexual abuse in Past Tense and surrogate motherhood in False Conception). Early on, I made Tanner a veteran of the Korean war so he could discuss military matters with a degree of expertise. (Because he aged much slower than the public at large, he had to became a Vietnam vet in the later books, to make the chronology work). My own military experience, I hasten to say, did not include combat, so references to such exploits were entirely fabricated. Various other personal experiences, though heavily fictionalized, pop up as well: growing up in a small Midwestern town (Fatal Obsession); attending a liberal arts college in the Upper Midwest (Southern Cross) and law school at Berkeley (Beyond Blame); and legal work in the agricultural industry (Strawberry Sunday). Q. You studied at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Literary references are frequently made in the Tanner series, including the writers he reads, such as Fitzgerald. What other authors of general fiction do you personally find interesting and as having something to say? Which writers did you find helpful and influential in your development as a writer, mystery fiction or not? A. I had written and sold the first Tanner novel before entering the workshop, so it had no influence on what I chose to write and little on how I chose to write it. Indeed, my book was frowned upon as “commercial fiction” by one of my instructors and I didn’t submit any mystery pieces for evaluation in the program. The workshop did, however, instill in me the idea that every word in a novel is a choice, and that the choice should be to write vivid and original prose that addressed the subject at hand in compelling terms. I didn’t always achieve that goal, but I always tried to. Some writers I read regularly include Richard Russo and Kent Haruf, because they write about small towns; John Updike and Graham Greene, because they write of squaring belief in a supreme being with the presence of suffering and sin in the world; Robertson Davies and Philip Roth, because they know so much about so many things; and Ward Just, because he respects the art of politics and writes about it with eloquence and expertise. I cut my mystery-reading teeth on Erle Stanley Gardner (I was sent home from the fifth grade for taking Perry Mason to school, mostly because of the decolletage on the cover. Long before I wanted to be Ross Macdonald I wanted to be Perry Mason.) I quickly grew to enjoy Richard S. Prather, the pre-McGee John D. MacDonald, and Rex Stout, among many others, and of course Hammett and Chandler. But Ross Macdonald was my model, beginning to end, in terms of both style and substance. Q. Mystery critics and reviewers have made comparisons of PI John Marshall Tanner to the private eye characters of Ross Macdonald, Raymond Chandler, and Dashiell Hammett. Was it a conscious decision on your part to write a so-called “literary PI” novel? Do you agree with this assessment? What updates or deviations did you undertake with the Chandler-Hammett PI model? A. I made Grave Error as much like a Ross Macdonald book as I could make it. I’m surprised he didn’t sue me. I liked his style, less operatic than Chandler and less apocalyptic than Hammet, a startling and penetrating vision of Lew Archer’s time and place. I also liked his focus on the psychological genesis of the murderous impulse, and the fact that he was regarded by many as a “serious” writer. Tanner was and remained pretty generic. Back in 1978, when I was circulating the first manuscript, everyone (in this context that means agents and editors) was telling me the private-eye genre was dead and I should write science fiction or fantasy if I wanted to be published. To me, however, the hard-boiled detective novel was an American art form on a par with jazz music, and I attempted to write something that would keep the concept alive rather than take it to a different place. (I take no credit for the fact that the agents and editors were entirely wrong and the form has clearly flourished.)  Q. Do you read a lot of mystery fiction yourself? Do you enjoy detective fiction more than hard-boiled crime novels, or vice versa. Which present day authors do you believe are perhaps underrated and whom you would suggest to our readers are worthy of their attention? A. I enjoy some of the new voices but I’m afraid I mostly reread my old favorites: Sjowall and Wahloo; Ross Thomas, etc., as well as writers I’ve already mentioned. Q. You’ve said that no further PI Marsh Tanner books will be written and you’ve essentially retired from writing. Why did you make the decision to take “retirement”? Do you have any regrets? Would you care to share any opinions on the state of today’s publishing industry, good or bad? A. My retirement was more forced than elected. When no publisher was willing to bring Strawberry Sunday out in softcover, even though it had been nominated for an Edgar, I knew Tanner’s day was done. Luckily I was able to write Ellipsis as the last chapter in the saga, and allow its subtext to suggest the reason my series had come to an end. I don’t see any need (or much demand) for the Tanner series to continue. I do plan to write more fiction, though it’s not likely to be anything of interest to major houses. Over the past two years I’ve turned a couple of (unproduced) screenplays of mine into novels and may publish them with iUniverse or some similar outlet. In the beginning, I was published by small imprints and edited by their editors-in-chief: Juris Jurjevics at Dial and Marc Jaffe at Villard. Both men liked the books and did their best to sell them within the limits of their corporate circumstances. After that I had no contact with the head of the house that published me, and Tanner became just another book. He didn’t survive the experience. (By the way, I never left a publisher before the person who brought me there had already departed, voluntarily or otherwise.) I don’t blame my own “ellipsis” on the publishing industry. Every author thinks more could have been done to promote him and his work, but the fact is, Tanner was around long enough for anyone interested in the genre to have taken a run at him. I hear the phrase “I read one of your books once” far too often for comfort (it’s much more damning than “I’ve never heard of you”), indicating that Tanner struck a chord with comparatively few readers. Q. Do you feel as if there is more that Marsh Tanner hasn’t had a chance to say? In Ellipsis (2000) we last leave him at his fiftieth birthday party in very different circumstances than throughout the previous books. Would he get back into the PI game, for instance? Would he continue his PI work late in life, say, like Michael Collins’ Dan Fortune or Bill Pronzini’s Nameless Detective? A. I did the best I could with Mr. Tanner for almost 30 years. At this point I don’t think I could write a better Tanner book than some that have gone before, making an attempt both repetitive and redundant. My efforts will be devoted elsewhere, though probably not far from the crime novel. It does give me pleasure, though, to imagine John Marshall Tanner spending his old age wrestling with the ethical dilemma of what to do with sudden and serendipitous wealth.  Q. The

cast of supporting characters in the Tanner books are

well-drawn and an integral part of his life and work as a PI.

Perhaps most memorable are Charlie Sleet, his SFPD cop friend, and

Ruthie Springer, his older and wiser PI sidekick. Did you

assemble this wonderful cast early in the series with plans to keep

them involved in future stories? Q. The

cast of supporting characters in the Tanner books are

well-drawn and an integral part of his life and work as a PI.

Perhaps most memorable are Charlie Sleet, his SFPD cop friend, and

Ruthie Springer, his older and wiser PI sidekick. Did you

assemble this wonderful cast early in the series with plans to keep

them involved in future stories? A. At first, I was just trying to draw some indelible character portraits, entirely from my imagination. I quickly realized, though, that Charlie and Ruthie played crucial roles in the stories. Charlie gave Tanner access to information only the police would have, as well as an audience to his ratiocination; Ruthie provided insights into aspects of Tanner’s character that wouldn’t normally emerge during a criminal investigation. His friends were also a reliable source of humor, I hope, always a good thing in a murder mystery. Q. The San Francisco setting provides a vivid and kinetic backdrop to the Marsh Tanner narratives. Why did you select San Francisco to base your PI yarns? What is your connection (spiritual or physical) to the city? A. When I started out, San Francisco was the only large city I knew well enough to write about without living in it. (I had lived in the city for several years while practicing law, but I was studying for the bar in Iowa City when I began Grave Error.) To me (and others) the P.I. was essentially an urban cowboy, making a gritty city setting derigeur. As years went by, I felt less strongly about that, and put Tanner on the road from time to time: to an Iowa town, the new South, the Salinas valley, and Seattle. Q. To me, your first novel in the series, Grave Error (1979), has a hard-boiled, rawer edge to it than the ones that came after. In later entries, Tanner rarely carries and even less often uses a handgun. The violence seems to flare up at climactic plot points in the narrative. Can you discuss your feelings about violence and how it relates to the books you have written, and more broadly, in the crime/suspense fiction writing of today? A. My interest in violence extends primarily to the prologue to and aftermath of such occasions. The depiction of violence in and of itself doesn’t have much appeal, partly because no matter how precise the prose, it necessarily pales before the actual experience. (The same is true of sex.) Also, I don’t enjoy carrying violent images around in my head for months on end while working them into a book. (The same is not true of sex.) As someone (Sidney Poitier, I think) recently said about movies, there are too many bodies and not enough tears. I tried to include the latter. Generally, I have written books about ordinary people whose experiences have shoved them into the extraordinary act of homicide. Both as reader and writer, I’m not much interested in serial killers, forensics, psychopaths, drug lords or mafiosi. I’m much more intrigued by why the guy next door suddenly murders his boss or why the checkout woman at Safeway suddenly disappears. Q. Some of the Marsh Tanner books address different social problems. The Edgar-nominated Strawberry Sunday (1999), for example, takes up the plight of the migrant crop pickers. Southern Cross (1993), set in Charleston, adopts as its theme racial prejudice. Were these novels an attempt to explore how our modern society operates in its various guises and ways? A. A writer’s primary task is to write his best. As the initial thrill of writing and being read and reviewed began to wane a bit, I tried to dramatize social issues that resonated with me in order to remain sufficiently engaged in the process, both physically and psychologically, to work at my peak. I believe in that regard, at least, I was successful. For the most part, the books got better and better. I also believe that, in part, the detective novel is an editorial, a vehicle through which the author expresses his sense of the world, warts and all. If you do it well, readers will keep reading just to hear what you have to say, but if you cross the line between demonstrable truth and subjective arrogance, many readers won’t forgive you.  Q. I’m curious about your pair of courtroom dramas, Impact (1989) and The Ditto List (1985). Were these titles written as a break in the Tanner series? Did your life in the legal profession find a need for fuller expression and exploration that was satisfied by writing these two books? A. The Ditto List came about because I wanted to write in depth about the relationship between men and women and I didn’t (and still don’t) think a PI novel was the place for that. I came up with the idea of a male divorce lawyer who represented only women as a way to present the case for both sides. I wrote Impact because I was beginning to suspect that Tanner’s book sales were still not such that he was a viable commercial commodity and I hoped to expand my readership by coming up with a best-selling thriller. No such luck. I was neither a divorce nor a personal injury lawyer, so I wasn’t delving into past experience, but as the subsequent tidal wave of lawyer books and movies has confirmed, the courtroom thriller is a great dramatic format. Q. Over the course of the Tanner books, how did they fare with mystery reviewers? Have you had much feedback from readers themselves? A. With minor exceptions, my reviews have been positive. In fact, it’s impossible to overemphasize how important The New Yorker’s reviews of Grave Error, especially, as well as several subsequent books, were in keeping me optimistic enough to continue writing in light of my minuscule sales. I’ve heard from several readers over the years, most of whom had generous and illuminating things to say (the exceptions mostly objected to my murderers using four letter words.) In the beginning, Otto Penzler wrote me an immensely kind word of encouragement and in the end, a woman from Pennsylvania whose name I don’t know wrote the nicest review I’ve ever gotten and posted it on Amazon.com. Q. Have you ever had any nibbles from TV or Hollywood? A. At the behest of Dustin Hoffman, Warner Bros. bought the movie rights to The Ditto List outright. He spent years trying to put the project together. At one point, Nora Ephron wrote a script and Mike Nichols was signed to direct. (And I was on my way to Seventh Heaven.) Sadly, despite Hoffman’s efforts and Warner’s money, the project never made it to the screen. Impact was under option to Universal for several years. Roger Towne (brother to Robert of CHINATOWN) wrote a script and Roman Polanski was willing to direct, but again, inertia won out, though not because Polanski was barred from this country. His art director assured him he could make Orly airport look like LAX. There has been no serious interest in the Tanner books by film or TV. Had I not foolishly waited until my eighth book to get an agent, things might have been different. Q. We’ve found only one short story that you’ve written: “Iris” (1984, The Eyes Have It). Are there others? As a writer you must have found it more comfortable in the long form than in the short. Is this true, or were there other reasons why you concentrated only on novels? A. “Iris” is my only short story. It was written to see how Tanner sounded in the third person. (Not all that great.) I’m not a very imaginative person, so if I have the merest glimmer of a plot idea, I’m going to pump it up to novel-size rather than squander it in a shorter format. (Come to think of it, “Iris” was published in a lot of places over the years, and more than earned its keep.) I do see life more in terms of a grueling marathon than a string of well-packaged epiphanies, so the novel form is more to my taste. Q. In concluding this interview, is there a question that we haven’t asked that we should have? Take the floor and ask it, if there is. In other words, is there anything you’d like to say in closing? A. I would like to conclude by saying that I feel fortunate that I was able to publish a Tanner novel in four different decades, that I thank all those who helped make my career possible, and I appreciate those who enjoyed the books and especially those who took the trouble to tell me so in one form or another. And I thank Mystery*File for taking an interest in Mr. Tanner and me. Q. Thank you, Mr. Greenleaf, for taking the time to talk with us. STEPHEN GREENLEAF: A BIBLIOGRAPHY - Compiled by Steve Lewis & Ed Lynskey The John Marshall Tanner books. Grave Error. Dial Press, May 1979. Paperback reprints: Ballantine, Jan 1982; Bantam, Dec 1991. Death Bed. Dial Press, Oct 1980. Paperback reprints: Ballantine, May 1982; Bantam, Dec 1991. State’s Evidence. Dial Press, May 1982. Paperback reprints: Ballantine, May 1983; Bantam, Dec 1991. Fatal Obsession. Dial Press, May 1983. Paperback reprints: Ballantine, April 1984; Bantam, Dec 1991. Beyond Blame. Villard Books, Dec 1985. Paperback reprint: Ballantine, Dec 1986. Toll Call. Villard Books, Feb 1987. Paperback reprint: Ballantine, Sept 1988. Book Case. William Morrow & Co., Jan 1991 Paperback reprint: Bantam, Dec 1991. ● Nominated for the Dilys Award, The Independent Mystery Booksellers Association, 1992. ● Received The Falcon Award, 1993, for the best private-eye novel published in Japan. Blood Type. William Morrow & Co., Sept 1992. Paperback reprint: Bantam, Sept 1993. Southern Cross. William Morrow & Co., Nov 1993. Paperback reprint: Bantam, Feb 1995. False Conception. Penzler Books, Nov 1994. Paperback reprint: Pocket, Mar 1997. Flesh Wounds. Scribner, Jan 1996. Paperback reprint: Pocket, Feb 1997. ● Nominated for the Shamus Award for Best Novel, Private Eye Writers of America, 1997. Past Tense. Scribner, Apr 1997. Paperback reprint: Pocket, Feb 1998. Strawberry Sunday. Scribner, Feb 1999. No paperback edition. ● Nominated for an Edgar Award for Best Novel, Mystery Writers of America, 2000. Ellipsis. Scribner, July 2000. No paperback edition. ● Nominated for the Shamus Award for Best Novel, Private Eye Writers of America, 2001. Non-series crime fiction. The Ditto List. Villard Books, Feb 1985. Paperback reprint: Ballantine, June 1986. Impact. William Morrow & Co., Sept 1989. Paperback reprint: Bantam, Oct 1990. Short stories. “Iris.” [John Marshall Tanner] First appeared in The Eyes Have It: The First Private Eye Writers of America Anthology, Robert J. Randisi, editor, Mysterious Press, 1984. ● Nominated for the Shamus Award for Best Short Story, Private Eye Writers of America, 1985. ● Reprinted in The Year’s Best Mystery and Suspense Stories 1985, Edward D. Hoch, editor, Walker & Co., 1985. ● Reprinted in The Mammoth Book Of Private Eye Stories, Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg, editors, Carroll & Graf, 1988. ● Reprinted in The 50 Greatest Mysteries of All Time, Otto Penzler, editor, Dove Books, 1998. ● Reprinted in The Best American Mystery Stories of the Century, Tony Hillerman & Otto Penzler, editors, Houghton Mifflin, 2000. “One to Three: A Fictionalized Memoir.” The Armchair Detective, Vol. 19, No. 4, Fall 1986. Mr. Greenleaf’s comments: This is a non-Tanner short story about a book signing where no one bought a book (based on actual experience, except that in the story the author sells one book at the end of the day and in real life, I didn't sell a single one). Non-fiction (partial). Introduction to Homicide Trinity, by Rex Stout (a story collection with Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin). Bantam, Rex Stout Library, paperback, July 1993. “Detective Novel Writing: The Hows and Whys.” The Writer, v.106, pp. 11-14, December 1993. “A Mystery in Three Acts.” The Writer, v.109, pp.11-13, April 1996. Sources: Allen J. Hubin, Crime Fiction IV. Stephen Greenleaf, email correspondence with Ed Lynskey. www.abebooks.com www.amazon.com www.thrillingdetective.com (Kevin Burton Smith) users.ev1.net/~homeville/msf (Mystery Short Fiction: 1990-2003, William G. Contento) ______________________________ YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. stevelewis62 (at) cox.net

Copyright © 2005 by Steve

Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors.

Return to

the Main Page.

|