|

Raffles:

Redeeming The Gentleman Burglar

by Mary Reed  Arthur “A. J.” Raffles

meets his future biographer

Harry “Bunny” Manders when at half past midnight a semi-hysterical

Bunny returns to A. J.’s rooms at the Albany to ask for funds to cover

cheques written for money lost gambling at baccarat earlier that

evening. Bunny’s financial embarrassment is such he’s been

selling furniture from his flat in fashionable Mount Street and he goes

so far as to threaten suicide. (FOOTNOTE 0) Arthur “A. J.” Raffles

meets his future biographer

Harry “Bunny” Manders when at half past midnight a semi-hysterical

Bunny returns to A. J.’s rooms at the Albany to ask for funds to cover

cheques written for money lost gambling at baccarat earlier that

evening. Bunny’s financial embarrassment is such he’s been

selling furniture from his flat in fashionable Mount Street and he goes

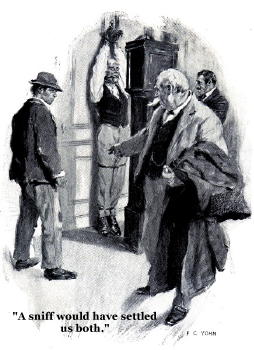

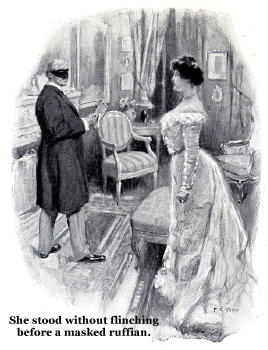

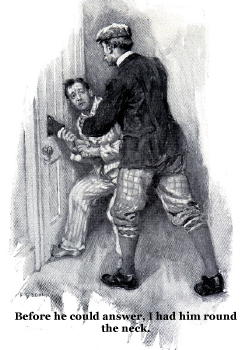

so far as to threaten suicide. (FOOTNOTE 0)The two young men are not total strangers, for ten years before they had known each other at public school, where Bunny fagged for Raffles, or in other words acted as an unpaid servant to the older boy as was and remains the custom at this type of educational establishment. (FOOTNOTE 1) One of Bunny’s more unusual duties was taking care of the “bald remnant” of a stuffed bird owned b Raffles. The school is not named, but it was originally a small country grammar school which within the past 50 years had evolved into a “great public school.” Bunny, desperate for a loan and believing Raffles would help him out since he is wealthy enough to play cricket each summer (at least until July when an understudy took his place) and lollygag about attending house parties and social events the rest of the time, reminds Raffles of his kindness during school days. Criminal prosecution apart, a bounced cheque spelt social ruin, as did other transgressions against what was considered “not done,” such as cheating at cards. But as it happens, Raffles is stony broke as well – and he’s only been able to keep himself afloat by engaging in the occasional spot of burglary. In order to salvage the situation Bunny, though initially operating under an impression deliberately fostered by Raffles that Mr Danby of Bond Street will lend them money, helps Raffles obtain this financial aid indirectly by aiding Raffles’ burglary of Danby’s jewelry shop early that morning – and thus begins their life of crime together. But had Raffles begun descending the slippery slope as far back as his school days? It’s true he was not only captain of the cricket eleven, fastest in the rugby team, and a champion athlete as well as (as Bunny puts it) “an ornament to the Upper Sixth.” (FOOTNOTE 2) However, at the same time Raffles commonly left the school dormitory at night to go into town, where surprisingly he seems to have gone unremarked, even though he ventured abroad disguised in loud clothing and a false beard. While rumours go around school about his leaving its grounds, he was never caught. His accomplice was Bunny, who pulled a rope up after Raffles has departed and put it down again when he returned from his nocturnal wanderings. It is never revealed what Raffles was up to during his absences, but he would have been only in his teens. He also went in for a spot of forging exeats. (FOOTNOTE 3) Even worse, the pair sometimes broke into fellow students’ studies by kicking in the door, although a discreet curtain is drawn over what, if anything, was subsequently removed without permission. After public school Raffles went up to Cambridge University, for which he batted; fifteen years later one of his fellow cricket eleven members is headmaster of the public school he and Bunny attended. What Raffles studied remains a mystery. Of Raffles’ family we glean little other than he is well born and that he has a sister of whom he thinks highly. She is married to a country vicar and lives in one of the eastern counties reached from Liverpool Street. (FOOTNOTE 4) When he visits, he reads the Sunday lessons to his brother-in-law’s congregation, an arrangement intended to get him into church. Neither Bunny nor he seem particularly religious, unusually for men of their class and time. There is also W. F. Raffles, an unmarried second cousin of his father’s. W.F. lives in Australia, where he manages a branch of the National Bank. Raffles is slim, with blue eyes (sometimes referred to as grey, so shall we say grey-blue, depending on available light?) and curly hair worn long but never untidy. His hair, originally black, turns prematurely grey or white, depending on which story you are reading. He has a clean-cut profile, is boyishly debonair, a superb dancer, an elegant dresser. A good shot and horseman, he is clean in his speech and rarely swears. Raffles is abstemious but goes into raptures over a (stolen) bottle of Mumm ’84 champagne.  Despite chain-smoking

Sullivans (FOOTNOTE

5),

carried in a silver cigarette case, Raffles is an excellent runner and

swimmer. He is in fine physical shape, able to handle not just

the occasional bout of fisticuffs but also to shin up porches and hoof

it across roofs -- not to mention casing promising houses by racing

after cabs taking travelers home from railway stations, so as to be on

hand to carry luggage into their houses, which gives him the

opportunity to see if they are worth burgling. Despite chain-smoking

Sullivans (FOOTNOTE

5),

carried in a silver cigarette case, Raffles is an excellent runner and

swimmer. He is in fine physical shape, able to handle not just

the occasional bout of fisticuffs but also to shin up porches and hoof

it across roofs -- not to mention casing promising houses by racing

after cabs taking travelers home from railway stations, so as to be on

hand to carry luggage into their houses, which gives him the

opportunity to see if they are worth burgling.Raffles is not only an ornament to society but also a superb amateur cricketer, “a dangerous bat, a brilliant field, and perhaps the very finest slow bowler of his decade,” as Bunny puts it. He plays for the Middlesex team (FOOTNOTE 6) – Bunny remarks the laws of the MCC (FOOTNOTE 7) are the only ones Raffles really respects – although claiming he has little enthusiasm for cricket, having found burglary a more exciting game. However, his fame as an amateur cricketer also serves as a cover for his real profession, since it would be commonly assumed a criminal would not engage in a very public career. It is for this reason that he encourages Bunny’s journalistic leanings. Raffles’ appreciation for the finer things of life means he keeps stolen silver and gold crested plate in his Albany rooms. His home is one of the expensive flats for wealthy unmarried men in what had been the town house of the Duke of York and Albany. (FOOTNOTE 8 ) His upstairs flat’s sitting-room is large and square with a marble mantelpiece and folding doors leading to his bedroom. When the stories open, heating is by coal fire and lighting by gas, although later improvements include electricity and a telephone. His rooms are richly carpeted, with luxurious furnishings; a carved oak bookcase, a grandfather clock, bureau, mahogany winecooler, and oak chests are in evidence. While there is little to reveal Raffles’ interest and prowess in cricket his decor demonstrates his aesthetic side. It appears Raffles admires the work of the Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood, since his walls are graced with several reproductions of their works, including George Frederic Watts’ Love and Death, Edward Burne-Jones’ The Golden Stairs, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel. Raffles owned some of these reproductions at school, for Bunny remembers dusting them. Raffles is also fond of quotations – to the extent of mentioning Keats as they return after a burglary Not surprisingly, with all these accomplishments, Raffles is quite the ladies man. In fact, Bunny expressly states he has purposely never written about Raffles’ experience of women “for it deserves another volume.” Raffles is, naturally, a Master of Disguise, which he considers indispensable when dealing with fences or while out on the job. He is well prepared for all eventualities; in “Mr Justice Raffles” he nonchalantly produces a false beard and a pocket make-up box, using their help to aid himself and Bunny escape detection. Posing as an artist, he has rented a pied-a-terre in an alley off the King’s Road. This studio provides a useful hideaway, as well as a place to store clothing supposedly intended for the models he somehow never finds. His disguises are so convincing that at times he even fools Bunny, most cruelly when pretending to be a policemen arresting poor Bunny at Raffle’s own funeral. Raffles will not hesitate to impersonate noted persons about town, aided by handing over calling cards stolen from trays in fashionable drawing rooms. He is still working on his Galloway Scots accent, although he can faithfully mimic several others – Cockney, plus “stage Irish, real Devonshire, very fair Norfolk, and three distinct Yorkshire dialects.” Later on, he learns to speak Italian. Despite his night work, Raffles abides by the unwritten rules of late Victorian life, one of which was there were certain things gentlemen simply did not do. However, he bends this implied code of conduct in an alarming fashion because while he will never rob his host, other guests’ valuables, particularly jewelry and gems, are fair game. On the other hand, while he cheerfully declares he would rob St Paul’s Cathedral, he would neither pinch money from a shop till nor steal a bag of apples from an old lady. He believes human nature resembles a draughts board, alternatively black and white, asking Bunny why should anyone be all one colour or the other? However, he has not entirely gone to the bow-wows for Bunny also assures us Raffles “liked the light the better for the shade.” On the other hand, Raffles has a lazy streak. He does not see why he should work when he can steal. He craves excitement and does not want a humdrum life “when excitement, romance, danger and a decent living [are] all going begging together...” (The Ides of March.) He disarmingly admits his outlook is wrong, but further excuses it by pointing out at the unequal way wealth is distributed, noting not everyone can be a moralist and besides which, he was not out burgling every night. However, he is not Robin Hood stealing for the poor; he is Raffles, stealing for himself.  Raffles does not

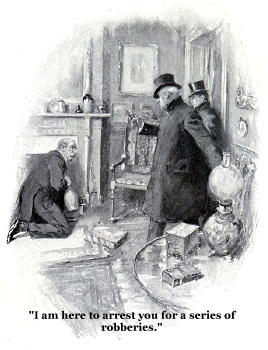

usually engage in violence although

he owns a life preserver. (FOOTNOTE 9)

In “The Chest of Silver” Raffles is forced to knock out a night

watchman in order to escape discovery, and the same treatment is meted

out to a constable in the British Museum in “A Jubilee Present.”

Then too, it is revealed in “The Fate of Faustina” that while living

incognito in Italy, he shot the man who killed Faustina, the woman he,

Raffles, loves – and then gives him a few more bullets for her sake,

with a cry of “Take that one to hell with you – and that – and

that!’ In “The Spoils of Sacrilege,” however, he deliberately

shoots wide when cornered, an incident Bunny states he believes was the

only time Raffles fired in his burgling career. Raffles does not

usually engage in violence although

he owns a life preserver. (FOOTNOTE 9)

In “The Chest of Silver” Raffles is forced to knock out a night

watchman in order to escape discovery, and the same treatment is meted

out to a constable in the British Museum in “A Jubilee Present.”

Then too, it is revealed in “The Fate of Faustina” that while living

incognito in Italy, he shot the man who killed Faustina, the woman he,

Raffles, loves – and then gives him a few more bullets for her sake,

with a cry of “Take that one to hell with you – and that – and

that!’ In “The Spoils of Sacrilege,” however, he deliberately

shoots wide when cornered, an incident Bunny states he believes was the

only time Raffles fired in his burgling career.And yet sometimes Raffles’ behaviour gives the reader pause. When Bunny appears in his rooms and threatens suicide by putting the barrel of his pistol to his temple, Raffles’ expression is not horror or fear but rather “wonder, admiration, and...pleased expectancy.” Bunny accuses Raffles of wanting to see him carry out his threat, and tellingly relates the response is “Not quite” – a reply “made with a little start, and a change of colour that came too late,” followed by Raffles’ admission he “was never more fascinated in my life.” At least the episode serves to convince Raffles Bunny is made of sterner stuff than might be apparent. (The Ides of March.) In the course of “Wilful Murder” he asks Bunny to think about a murderer visiting their club, “talking to the men, very likely about the murder itself; and knowing you’ve done it; and wondering how they’d look if THEY knew!”, adding “Oh, it would be great, simply great!” He makes these disturbing comments – or are they intended to further stoke Bunny’s hero worship? – while admitting to contemplating doing away with Angus Baird, a fence and money lender. Baird has discovered their secret life and Raffles fears he will blackmail them as well as taking bribes from the police for information. In addition, Baird’s predatory practices are ruining Jack Rutter, a mutual friend, who is taking to drink and being cut by acquaintances as a consequence. As it transpires, after breaking into Baird’s house, Raffles and Bunny find Rutter, who has already killed Baird in self defence. Rutter is ready to give himself up for getting rid of “a robber, a usurer, a jackal, a blackmailer, the cleverest and the cruellest villain unhung.” Raffles persuades him to abandon the idea and aids his escape by taking him to Liverpool and seeing him on his way to America in steerage. In “The Return Match” a fellow burglar named Reginald Crawshay has deduced the pair’s situation and having broken out of Dartmoor Prison (FOOTNOTE 10) appears in Raffles’ rooms to ask for aid in getting abroad – with the understanding if it is refused, he will blow the whistle on his fellow criminals. Raffles helps him leave the country. Raffles commits the terrible sin of abandoning his friend. When they are apprehended aboard ship after an unsuccessful attempt to steal a large pearl in “The Gift of the Emperor,” he deserts Bunny, shouting to him to hold back the pursuers to allow him, Raffles, time to dive overboard and make for the Island of Elba. Without thinking of his own fate, Bunny obeys. Raffles escapes, but Bunny does not. And this is even though Raffles is fond of his biographer, whom he addresses as his “dear rabbit” as well as “Bunny,” pulling his leg with such comments as Bunny having “grown such a pious rabbit in your old age!” And what about his dear rabbit Bunny? (FOOTNOTE 11) We know less about him, although he mentions as a boy he lived in a southern county less than 40 miles from London on the London & Brighton Railway and comments in “The Raffles Relics” and “The Spoils of Sacrilege” reveal the Manders family home was on a lane next to St Leonards Forest, near Horsham. (FOOTNOTE 12)  The Manders home was

built in the late 1860s or

early 1870s but is no longer owned by Bunny’s family. His father

grew prize-winning peaches and the family was well off. Their

home boasted a porch tower, ornamental iron balconies (because they

provided such easy access to the house, Bunny feared burglars as a boy

and looked under his bed each night!) and a flagstaff. There are

stables and a large garden at least a hundred yards long, with lawns

and banks of rhododendrons fringing a small lake dug out when Bunny was

a boy. The Manders home was

built in the late 1860s or

early 1870s but is no longer owned by Bunny’s family. His father

grew prize-winning peaches and the family was well off. Their

home boasted a porch tower, ornamental iron balconies (because they

provided such easy access to the house, Bunny feared burglars as a boy

and looked under his bed each night!) and a flagstaff. There are

stables and a large garden at least a hundred yards long, with lawns

and banks of rhododendrons fringing a small lake dug out when Bunny was

a boy.After finishing public school Bunny, an only child whose parents are dead by the time we meet him, came into his inheritance about three years before he appeared in Raffles’ rooms in such dramatic fashion. Having become wealthy, he did not take the usual path of young men of his class and go up to university after public school, but being young and foolish squandered everything. Given he would have entered university at 18, it seems likely when the stories begin he is not much older than 21 and Raffles a year or two his senior. (FOOTNOTE 13) The only other relative Bunny mentions is an anonymous near kinsman, “a knighted specialist whose consulting-room is within a cab-whistle of Vere Street.” (No Sinecure.) Bunny’s nickname is never explained, but a few hints are given. He is timid and as is demonstrated more than once is easily led. We know little about his appearance: he has fair hair, worn long in earlier days, and a scarred hand as a result of stopping a scoundrel shouting for help and presumably getting badly bitten as a result. There is a distinct impresion Bunny is rather womanish in some ways. Few men would mention how well the Cambridge cricket team’s light blue sash and hat suit Teddy Garland, the young wicket keeper, as in Mr. Justice Raffles, and in “The Ides of March” Bunny notices on their first burglary that Raffles carries the tools of his trade in “a pretty embroidered case, intended obviously for his razors.” In “The Rest Cure,” Bunny and Raffles take over a house in Campden Hill, (FOOTNOTE 14) temporarily unoccupied because its owner, an inspector of prisons named Colonel Crutchley, (FOOTNOTE 15) is holidaying in Switzerland. As a witty jape Bunny dresses up in Mrs Crutchley’s clothing to give Raffles a fright. However, the colonel returns unexpectedly and the experiment is never completed. Bunny is not such a quick thinker on his feet as Raffles, and can be dangerously slow. Towards the end of “The Last Laugh” he sees the pinioned and gagged Raffles who, having run afoul of the Camorra (FOOTNOTE 16) as a result of the Italian business mentioned above, is about to be killed by a device worthy of Sax Rohmer – a grandfather clock wired to trigger a revolver at a certain time. However, it is the urchin who finds and brings Bunny to the house to rescue Raffles who knocks the clock over and saves Raffles’ life. On the other hand, when Raffles is temporarily blinded and bloodied in “Mr Justice Raffles” Bunny comes to the rescue by leaping upon and rendering unconscious Raffles’ attacker. Social class was all important and the pair are only too aware of it. Raffles characterises another high born thief as being in and of society, describing society as arranged “in rings like a target, and we never were in the bull’s-eye, however thick you may lay on the ink!” (To Catch a Thief.) Another demonstration of class awareness is when Raffles bitterly mentions he has not forgotten a house party to which he was invited because he was a good cricketer, rather than because he was a social equal. This class consciousness is underlined in a way ludicrous to modern eyes. Dan Levy, another moneylender, earns Raffles’ “sudden respect” in Mr Justice Raffles because he is wearing silk pyjamas when he interrupts Raffles’ burglary of the Levy hotel rooms at a health spa in Carlsbad. Raffles subsequently confesses to Bunny that Levy’s nightwear led him to realise “mud baths mightn’t be the only ones he ever took.” When Bunny later meets Levy, who is dressed like a gentleman, the sight fills him with “that inconsequent respect which the silk pajamas had engendered in Raffles.” Bunny also displays culinary snobbishness, sniffily telling the reader he does not drink bitter – although when Raffles imbibes a tankard or two in the same novel, he sympathetically keeps him company. More tellingly, he clearly shows his snobbish side when talking about E.M. Garland, the afore-mentioned Teddy. Mentioning Teddy had attended Eton (FOOTNOTE 17) and Trinity College at Cambridge University and had hit it off with Raffles due to their mutual love of and expertise in cricket, Bunny admits he’s somewhat prejudiced against Mr Garland senior, whom he has never met but knows is a retired brewer. A fortune earned by soiling the hands with trade was generally considered infra dig in upper crust society, yet when Bunny and Teddy’s father finally meet, he finds Mr Garland senior to have kindly eyes and a gentle manner and is won over right away. Bunny does not care much for Teddy, although they had met at the Albany a couple of times. This is all the more appalling when we learn, as in Bunny’s case, it is to Raffles Teddy has turned for help when in desperate financial straits – and aid is rendered even though Teddy is found attempting to forge one of Raffles’ cheques! Raffles also helps Mr Garland senior escape the clutches of the same usurer. Much later, when Bunny, now 40ish, a little chubby, and wearing glasses for short sightedness, meets Teddy by accident at the Hammam Turkish Bath (FOOTNOTE 18), he learns Camilla Belsize, Teddy’s wife, was newly engaged to Teddy at the time of the cheque business. When Teddy as a man of honour offered to release her from the engagement, she refused. It transpires Camilla is a woman Raffles himself loved, to the extent of admitting if he was not the sort of cad he was, he would have proposed marriage and settled down. But because he was what he was he had deliberately cut off their relationship, and thus it was for the sake of both Teddy and Camilla he had helped out father and son. At that point, Teddy’s loyalty to, and praise of, Raffles wins Bunny’s heart. Bunny’s own love affair is interrupted by events. Although engaged when he throws in his lot with Raffles, he breaks it off because by his lights it is the honourable thing to do. His beloved, always anonymous because her name must not be tainted by connection with his, is an orphan who lives most of the year with a well-born aunt in the country and the rest of the time in the London house of politician Hector Carruthers.  Raffles misleads Bunny in

order to get information

on the layout of the house, telling him Palace Gardens no longer knows

the name of Carruthers. Which is quite true as far as it goes,

for Carruthers is now Lord Lochmaben. Bunny does not care about

the moral aspect since he thinks his engagement is dead, and anyhow his

beloved no longer resides there, or so he thinks. However,

although Raffles does not want him to assist with the burglary, he

insists on accompanying him and to his horror, finds members of the

family are in fact in residence, and not only that but his beloved sees

and hides him in order to help him escape. Raffles misleads Bunny in

order to get information

on the layout of the house, telling him Palace Gardens no longer knows

the name of Carruthers. Which is quite true as far as it goes,

for Carruthers is now Lord Lochmaben. Bunny does not care about

the moral aspect since he thinks his engagement is dead, and anyhow his

beloved no longer resides there, or so he thinks. However,

although Raffles does not want him to assist with the burglary, he

insists on accompanying him and to his horror, finds members of the

family are in fact in residence, and not only that but his beloved sees

and hides him in order to help him escape.This terrible betrayal of trust, which Raffles excuses by telling Bunny the politician’s elevation was in the newspaper and he would have seen it if he had paid closer attention, causes a breach in their friendship, which only heals when Raffles comes to Bunny’s flat. For Bunny both admires and loves Raffles; there is a strong element of hero worship in his narration and he freely admits to jealousy of Raffles’ other friends of both genders. He speaks of Raffles’ “gallant glamour”, his humour, gaiety, and courage, his “jaunty jeux d’esprit,” resourcefulness, and audacity. He declares it is not the villainous Raffles he cares about, but the sportsman. Indeed, Raffle’s witty charm cause both men and women to love him. Bunny is not, however, completely blind to Raffles’ shortcomings. Describing him as “strong and unscrupulous,” he complains more than once of his friend’s “capricious reserve” and how Raffles sometimes conceals his full plans to the extent of occasionally using him as an unwitting catspaw. He also resents Raffles’ occasional lack of confidence in him. Bunny further states he has omitted “heinous episodes” while dwelling “unduly on the redeeming side” of their dark life, and the reader may well ask how was it Raffles fell into living in such a fashion? According to “Le Premier Pas” (“The First Step”) Raffles embarked on his criminal career more or less by accident. Strapped for cash while on a cricketing tour of Australia and temporarily not able to play due to a hand injury, he decided to ask his relative in the banking business for assistance. It transpires the other Raffles has been transferred to a bank branch some distance from Melbourne, but has not yet arrived to take up his duties. A. J., asked upon arrival if he is Mr Raffles, naturally says he is, and eventually realises he has been mistaken for the other Raffles. Succumbing to temptation, he obtains the bank keys and makes off with a couple of hundred sovereigns. After arriving back at Melbourne A. J. shaves off what had been a heavy moustache, thereafter remaining clean-shaven except when in disguise. Another conundrum is how Raffles made his acquaintance with fences and where he obtained the tools of his trade. We are never told, but his knowledge is extensive and his implements many, if somewhat primitive. They include a jimmy, rock oil (applied to lessen the noise of his brace and bit when cutting holes around a lock in order to remove it), skeleton keys, and the gimlets and wedges used to jam doors. Bunny also mentions a type of forceps used to turn keys on the far side of a door. What’s more, some of these items are concealed about Raffles’ person whenever he is out in his evening clothes, so he is obviously prepared for all eventualities and opportunities. Raffles also employs traditional squares of brown paper spread with treacle, pressed to windowpanes to prevent them falling to the ground after being cut out with a diamond. A whiff of chloroform is occasionally applied and on at least one occasion a sleeping aid is used. (FOOTNOTE 19) Raffles also improves his shining hour by inventing a velvet bag with elasticated ends which he wears like a muff. This contrivance deadens the noise of filing counterfeit keys, although Raffles’ handling of the item is intended to suggest that it is a tobacco pouch when relics of his career go on display in New Scotland Yard’s Black Museum (FOOTNOTE 20) – naturally, he steals them back. (The Raffles Relics.) Another Raffles invention involves a child’s fishing rod. Its pieces are hidden in a bamboo cane used in normal fashion and when re-assembled, a double steel hook is attached to one end. A long manila rope fitted with foot loops, which Raffles carries wound around his waist, is tied to one side of the hook. The other side grabs whatever handy anchoring point the rod can be extended to reach, and up goes Raffles. In this connection he speaks fondly of drainage pipes, which in the UK routinely run down outside walls. A somewhat flamboyant aspect of Raffle’s character is displayed by his wearing a Burglar Bill mask as appropriate – and insisting Bunny do the same.  As mentioned, when the

pair are arrested aboard ship

Raffles dives overboard to swim for land. At this point he is

presumed drowned while Bunny is convicted, serving l8 months in

Wormwood Scrubs. (FOOTNOTE 21) As mentioned, when the

pair are arrested aboard ship

Raffles dives overboard to swim for land. At this point he is

presumed drowned while Bunny is convicted, serving l8 months in

Wormwood Scrubs. (FOOTNOTE 21)Raffles’ creator, E. W. Hornung, was married to Constance, Arthur Conan Doyle’s sister, and dedicated the first collection of Raffles stories to his brother-in-law. (FOOTNOTE 22) Like Doyle’s protagonist Sherlock Holmes, thought to have perished at the Reichenbach Falls, Raffles returns after an incognito sojourn in Italy, having safely reached land after a ten mile swim. By then it is May 1897 and Bunny is out of jail, trying to scratch out a living writing about prison life. They meet again through a typical Rafflian machination involving a personal advertisement in the Daily Mail and a forged telegram supposedly from Bunny’s knighted relative, urging Bunny to apply for the advertised job of nurse to an invalid. Bunny is surprised, given after his fall from grace his relative had forbidden him in no uncertain terms to ever set foot again in his house and yet the telegram says he will speak for Bunny if necessary. Bunny applies, only to discover the invalid, Mr Maturin, is Raffles, posing as a seriously ill Australian who is not long for the world and wishes to die in London. Although Bunny’s articles about prison life are being published anonymously, Raffles recognised “the fist was the fist of my sitting rabbit!” and wheedled Bunny’s address from his editor in order to send the forged telegram. Raffles has suffered, for his hair is now white and his face more lined. Bunny remarks his friend had “aged twenty years; he looked fifty at the very least.” This suggests that by then they were in their early 30s, meaning their criminal career had already lasted some years if my guess Bunny was about 21 when the stories begin is on the mark. Reunited, they return to the old life. A threat appears from an unexpected source: Jacques Saillard, a female artist despite the name and one of Raffles’ old flames, recognises him during, you have it, a burglary. Raffles is presented with the choice: she will leave her husband and elope with Raffles or Raffles be turned in to the police. Raffles sends Bunny away, ostensibly to find another place to live since the woman has located their flat – again without telling him the full plan -- and then bribes his medical attendants to certify him as having died yet again, this time from typhoid. Bunny, of course, believes it and is grief stricken before he realises the true situation. Having thus escaped the long arms of both woman and the law, by December 1899 they have taken up residence in a cottage next to Ham Common (FOOTNOTE 23) with a landlady who takes good care of them, spoiling Raffles in particular. Bunny presents himself as an author and Raffles as his brother Ralph, just returned from Australia and a sick man “with a curious affection of the eyes ... necessitating the use of clouded spectacles in the open air” – an effective excuse for an equally effective disguise. (The Wrong House.) There is a rash of burglaries in the area the winter they move into the neighbourhood, which strangely coincides with the pair being public spirited enough to go out on night patrol riding bikes. Raffles has a Beeston Humber and Bunny a Royal Sunbeam, but both are fitted with Dunlop tyres, for as Raffles remarks Dunlops appear to be the most popular type and therefore there was less likelihood of their being traced through their tracks. (FOOTNOTE 24) For all their illegal activities, Raffles and Bunny are men of their time, with the typical love of queen and country of that era. They drink a loyal toast to Victoria on the occasion of her Diamond Jubilee (FOOTNOTE 25) after Raffles has sent her a beautiful gold cup stolen from the British Museum. There is also the matter of a priceless pearl the German Emperor proposed to present to the King of the Cannibal Islands after the latter “made faces at Queen Victoria.” As patriotic Englishmen they plan to steal it but are caught; it is this attempted theft that leads to Bunny doing time and Raffles disappearing into Italy. There is also an element of wistful love of country in Raffles’ remarks in Mr Justice Raffles that the lights along the Embankment (FOOTNOTE 26) form “the finest necklace in the world,” while “Big Ben was the Koh-i-noor of the London lights.” (FOOTNOTE 27) More than once Raffles claims he intends to give up his life of crime once he has made a good amount from thieving, but fate decrees otherwise, for Raffles dyes his hair ginger and the pair travel to South Africa to enlist in a horse regiment fighting in the Boer War. (FOOTNOTE 28) The bumbling and inept Bunny is constantly picked upon by their fellow soldiers, and at one point Raffles comes to his rescue by getting into fisticuffs with one Corporal Connal, who had been particularly beastly to Bunny. Disaster strikes when Raffles is recognised by Peter Bellingham, an old acquaintance who is now a captain in the infantry – and what’s worse, they are rumbled just after they have for once returned to old habits and stolen a few bottles of whiskey. However, after an hour or so talking about cricket while having a whiskey and soda or two they go back to their quarters. Ironically, Bunny complains during this chat that “the snob [Bellingham] never addressed a syllable to me.” (The Knees of the Gods.) By ill fortune, Corporal Connal has been eavesdropping, and when Raffles and Bunny catch him aiding the enemy, he threatens to expose their true identities. Despite this, the pair turn him in and in a subsequent interview with their general are told to carry on fighting while he looks further into the matter.  Thus it is that in a

skirmish taking place hours

after the traitor Connal is executed Raffles is killed and Bunny

wounded and lamed for life. Thus it is that in a

skirmish taking place hours

after the traitor Connal is executed Raffles is killed and Bunny

wounded and lamed for life.We do not know the day Raffles dies, but he is gone by late June 1900. His final words emphasise his love of excitement: “It’s not only been the best time I ever had, old Bunny, but I’m not half sure –” When Bunny returns to England, he meets his former fiancee by accident. It is only then he learns Raffles had returned the night after their abortive attempt to burglarise her home in order to explain he had brought Bunny to the house on false pretences. Bunny’s beloved shrewdly observes that, while she cannot condone the life they led, she realises Raffles lived the way he did because he loved adventure and danger, and Bunny had been what he had been because he loved Raffles. She also speaks of Raffles’ personal magnetism, his “glamour”, and how it persuaded people to follow him, a succinct explanation of why Bunny was devoted to Raffles, though his devotion led him into the jaws of ruin and imprisonment. Her kind letter, which mentions her aunt had died after, it appears, providing for her financial independence for she writes from her own home, gives Bunny the hope they will reconcile and marry after all. Thus as the stories close there is a hint Bunny’s life will become more regular if less exciting – although it is clear he will always miss Raffles. Raffles certainly did not behave like a gentleman in the true sense, nor could the era’s readers in all conscience approve of his activities, although they certainly enjoyed reading about them. Unlike our time, a thief could not be a hero and so it was inevitable Hornung would ring down the curtain on Raffles and Bunny by allowing them to redeem themselves as true patriots – Bunny by being wounded in the service of his country and Raffles by dying in battle. Towards the end, Raffles hinted he has become sick of his life. It is possible he had also realised he would be caught sooner or later, not to mention he could not possibly continue burgling into old age. It seems likely he enlisted partly to avoid the shame his inevitable imprisonment would bring him and partly to try to atone somewhat for his life. As Raffles remarks to Bunny before they leave for South Africa, if they were killed there “it was the death to die,” and quicker than illness or being hanged. Indeed, he muses, what was there to come back to in England? For Raffles, death for queen and country was an honourable way to depart the stage. The outbreak of World War I was only five years away as the adventures close. For the modern reader, knowing that world was so soon to depart forever adds a poignant, sad overlay to the long, golden afternoon of the era in which Raffles and Bunny moved in these lightly written and entertaining glimpses of late Victorian life. Illustrations by F. C. YOHN NOTES (0) Recently spotted was another resident of The Albany in “The Stolen Body” by H. G. Wells http://www.classicreader.com/read.php/sid.6/bookid.174/ “Mr.

Bessel was the senior partner in the firm of Bessel, Hart, and Brown,

of St. Paul’s Churchyard, and for many years he was well known among

those interested in psychical research as a liberal-minded and

conscientious investigator. He was an unmarried man, and instead

of living in the suburbs, after the fashion of his class, he occupied

rooms in the Albany, near Piccadilly.”

If walls could talk...

(1) In the UK, a private school with fee-paying pupils. (2) The most senior class. (3) Permission to leave the school grounds. (4) Liverpool Street Railway Station in northeast London. (5) Still manufactured. Bunny refers to them as Egyptians, and a packet of Sullivans’ Oriental brand can be seen at http://195.2.85.140/21140.JPG (6) Middlesex Cricket Club. (7) Marylebone Cricket Club in London. Recognised as the premier team, it still runs Lord’s Cricket Ground, “the home of cricket.” (8) An illustrated history of The Albany is on-line: http://www.georgianindex.net/albany/Rooms_at_the_Albany.html (9) A type of cosh.  (10) Dartmoor Prison in Devon,

considered the most severe

penal institution in l9th century Britain. Dartmoor itself was

also the setting for Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles. (10) Dartmoor Prison in Devon,

considered the most severe

penal institution in l9th century Britain. Dartmoor itself was

also the setting for Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles.(11) A fellow public school pupil, now a London solicitor, is still referred to by his nickname of Mother Hubbard. (12) Town in Sussex. (13) Since Raffles remarks some of the characteristics of the Manders house are shared with “almost every house of a certain size built about thirty years ago,” “The Spoils of Sacrilege” can be dated as taking place fairly close to either side of the turn of the century. (14) Part of the Kensington district of London. (15) The fictitious Colonel Crutchley is said to have earned a VC at Rorke’s Drift, fought during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. A detailed account of the battle and its aftermath by a former curator of the Rorke’s Drift Museum is at http://www.battlefields.co.za/history/anglo-zulu_war/rorkes_drift/rorkes_gs.htm (16) A secret society based in Naples. (17) Possibly the most famous public school in England, although Harrow would doubtless challenge this assertion! (18) In Jermyn Street. The office of Dan Levy, the money lender who ensnared both Garlands, was in the same street. (19) Somnol. An identically named sleeping aid is still prescribed. (20) More properly known as the Crime Museum, it opened in 1875 and moved to New Scotland Yard in 1890. The LondonMetropolitan Police page devoted to this museum mentions that both Hornung and Arthur Conan Doyle were visitors. See http://www.met.police.uk/history/crime_museum.htm (21) Prison in west London. (22) It has been suggested Hornung’s creation of Raffles and Bunny was intended to poke gentle fun at Holmes and Watson by featuring a pair of similar protagonists who were working on the other side of the law – not to mention Raffles’ first name is the same as Conan Doyle’s. (23) Ham in Surrey was a favoured suburban area for London businessmen and the well-to-do, with many fine houses. (24) In Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Priory School,” Holmes reveals he is familiar with the marks made by 42 different bicycle tyres. In Doyle’s story the tracks mentioned are those left by Dunlop and Palmer tyres. (25) Marking Victoria’s 60 years as monarch, placing “A Jubilee Present” in 1897. (26) Described by a writer in the 1890s as “the greatest achievement of the late Metropolitan Board of Works,” the Embankment, the wide boulevard alongside the River Thames, was constructed between 1864 and 1870. (27) The Koh-i-Noor diamond was presented to Victoria in 1850 after the British annexed the Punjab in India. The enormous gem, whose name means “mountain of light,” is part of the Crown Jewels. (28) Popular name for the South African War of 1899-1902. E-TEXTS:

Raffles’ adventures began in “The Ides of March,” published in Cassell’s Magazine in 1898. The stories have been collected in three anthologies and there is also a novel. SHORT STORIES: The Amateur Cracksman < http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext96/amatc10.txt> Contents: “A Costume Piece” Cassell’s, July 1898. “Gentlemen and Players” Cassell’s, August 1898. “The Gift of the Emperor” Cassell’s, November 1898. “The Ides of March” Cassell’s, June 1898. “Nine Points of the Law” Cassell’s, September 1898. “Le Premier Pas” 1899 “The Return Match” Cassell’s, October, 1898. “Wilful Murder” The Black Mask. US: Raffles: Further Adventures of the Amateur Cracksman <http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext96/rafls10.txt> Contents: “The Fate of Faustina” Scribner’s, March 1901. “A Jubilee Present” Scribner’s, February 1901. “The Knees of the Gods” “The Last Laugh” Scribner’s, April 1901. “No Sinecure” Scribner’s, January 1901. “An Old Flame” Scribner’s, June 1901. “To Catch a Thief” Scribner’s, May 901. “The Wrong House” 1899. A Thief in the Night <http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext00/thfnt10.txt> Contents: “A Bad Night” “The Chest of Silver” “The Criminologists’ Club” “The Field of Philippi” Colliers, April 29, 1905. “The Last Word” “The Raffles Relics” “The Rest Cure” “The Spoils of Sacrilege” “A Thief in the Night” Entitled “Out of Paradise” in the US edition. “A Trap to Catch a Cracksman” The Pall Mall Magazine, July 1905. NOVEL: Mr. Justice Raffles <http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext06/7raff10.txt> SOURCE: Allen J. Hubin, Crime Fiction IV. YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME.

Copyright © 2006 by Mary Reed.

|